An important feature of the medical profession is to provide compassionate and empathic care to patients. Physicians need up to date knowledge and appropriate skills to provide better patient care.1 Professionalism is a core quality that needs to be understood and developed as part of becoming a doctor. It brings together many aspects of how a medical student learns about and contributes to the care of patients. A teachers’ professional attitude is a role model for learners. Medical educationists and teachers should foster the development of professionalism among learners. Both personal and environmental factors play a role in physician’s professionalism.2 Various factors contribute to professionalism, which may allow the development of more effective approaches to promote this quality in medical students.

Medical professionalism forms the basis of the contract between doctors and patients. The General Medical Council’s (GMC) publication, Good Medical Practice, outlines the principles of professional behavior for medical students under the categories providing good clinical care, maintaining good medical practice, teaching and training, relationships with patients, working with colleagues, probity, and health.3 It is mandatory that professionalism is incorporated into the undergraduate curriculum so students can learn this attribute from the very beginning. The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) established Project Professionalism, which sought to define the components of medical professionalism, including altruism, accountability, excellence, duty, honor/integrity and respect.4 It is clear that the development of professionalism evolves over time by a process of exploration and reflection.5

The medical profession now recognizes the importance of professionalism in medical students and wants to promote curriculum integration and early introduction of experiential learning in the undergraduate curriculum.6 Medical education and curriculum should provide multiple learning opportunities for gaining experience in and reflecting on the concepts and principles of medical professionalism for better patient care.7 Doctors’ actual behavior in clinical practice determines professionalism. This quality requires integrity, honesty, the ability to communicate effectively with patients, and respect for patient autonomy.8 Medical students learn professionalism during the course either by direct teaching or experiential learning that help students to prioritize their learning needs and make the best use of the time available.9

The learning experience, with feedback from teachers and peers, helps students to learn appropriate professional attitude in clinical practice. Professionalism is a characteristic that cannot be established effectively without the direct participation of the learner with both a willingness and an attitude to change.10 Encouraging students to experience a sense of responsibility may help them to build team working skills and self-directed learning and professionalism.11 Feedback on professionalism must be based on valid and reliable observations. Teachers need to understand how their students view themselves and their professional roles.12–14

The purpose of this study was to estimate the self-reported level of practice of the core elements of professionalism by medical students and medical faculty and compare the two groups.

Methods

The study comprised of a survey of medical students, clinicians, and teaching faculty members using a self-reported questionnaire. The questionnaire comprised of four sections. The first section consisted of demographic details of participants and sections two to four contained questions on professional knowledge and skills [Table 1]. Each question had five response options (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree). The last section included the essential components of professionalism.

Table 1: Students’ perception of their professional knowledge and skills.

|

Professional knowledge

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I am up to date with my knowledge of basic and clinical sciences and clinical competency

|

11 (10.1)

|

74 (67.9)

|

20 (18.3)

|

4 (3.7)

|

0 (0.0)

|

|

Professional skills

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I can do self-management planning for learning

|

7 (6.4)

|

46 (42.2)

|

19 (17.4)

|

34 (31.2)

|

3 (2.8)

|

|

I am able to do self-restraint/risk management

|

4 (3.7)

|

63 (57.8)

|

29 (26.6)

|

13 (11.9)

|

0 (0.0)

|

|

My physical health is appropriate

|

33 (30.3)

|

57 (52.3)

|

10 (9.2)

|

7 (6.4)

|

2 (1.8)

|

|

My mental health is appropriate

|

60 (55.0)

|

39 (35.8)

|

2 (1.8)

|

5 (4.6)

|

3 (2.8)

|

|

I have lifelong learning skills; I can solve problems and make appropriate decision, self-directed learner

|

21 (19.3)

|

61 (56.0)

|

25 (22.9)

|

1 (0.9)

|

1 (0.9)

|

|

I can do team work

|

18 (16.7)

|

70 (64.8)

|

19 (17.4)

|

1 (0.9)

|

1 (0.9)

|

|

I have good communication skills

|

20 (18.3)

|

62 (56.9)

|

22 (20.2)

|

4 (3.7)

|

1 (0.9)

|

|

I am comfortable with foreign language skills

|

5 (4.6)

|

22 (20.4)

|

16 (14.7)

|

48 (44.4)

|

18 (16.7)

|

|

I have creative/logical/critical thinking

|

24 (22.0)

|

70 (64.2)

|

10 (9.2)

|

5 (4.6)

|

0 (0.0)

|

|

Professional Attitude

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I understand hospital/clinic setup (service oriented)

|

20 (18.3)

|

72 (66.1)

|

15 (13.8)

|

2 (1.8)

|

0 (0.0)

|

|

I have respect for others and myself

|

65 (59.6)

|

43 (39.4)

|

1 (0.9)

|

0 (0.0)

|

0 (0.0)

|

|

I am a role model

|

24 (22.0)

|

52 (47.7)

|

30 (27.5)

|

3 (2.8)

|

0 (0.0)

|

|

I have good etiquette/humanity

|

55 (50.5)

|

52 (47.7)

|

2 (1.8)

|

0 (0.0)

|

0 (0.0)

|

|

I prefer ethical thinking and behavior

|

11 (10.1)

|

18 (16.5)

|

14 (12.8)

|

46 (42.2)

|

20 (18.3)

|

|

I am self-confident

|

8 (7.3)

|

40 (36.7)

|

27 (24.8)

|

25 (22.9)

|

9 (8.3)

|

|

I always maintain integrity/honesty

|

39 (35.8)

|

61 (56.0)

|

6 (5.5)

|

1 (0.9)

|

2 (1.8)

|

|

I do regular self-assessment

|

7 (6.4)

|

27 (24.8)

|

38 (34.9)

|

29 (26.6)

|

8 (7.3)

|

|

I have appropriate appearance/behavior

|

47 (43.1)

|

57 (52.3)

|

3 (2.8)

|

2 (1.8)

|

0 (0)

|

|

I am fully aware of patient safety

|

38 (34.9)

|

56 (51.4)

|

11 (10.1)

|

3 (2.8)

|

1 (0.9)

|

Data presented as n (%).

The ethical review committee approved the questionnaire, and participants were enrolled after obtaining written informed consent. Two research assistants were educated about the questionnaire and were trained in the data collection procedure, which included identification, recruitment, data collection, and obtaining written informed consent. The questionnaire was developed as a result of a literature search for studies of core elements of medical professionalism measures. The questionnaire was reviewed and finalized after several brainstorming sessions and discussions so that the questionnaire would maximize the validity and reliability. Previous studies have suggested methods to improve response rates by including a relevant topic, offering feedback, the length of questionnaires, and assurance of confidentiality, incentives, and personal contact. All questionnaires were included in the analysis, and there were no missing responses.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics (SPSS Statistics Inc., Chicago, US) version 20.0. Data was expressed in frequencies and percentages for questionnaire responses that were numerical. Cross tabulation was performed to determine if there was a relationship between subgroups. The chi-square test was used for categorical data and the Mann-Whitney test to compare differences between two groups with non-parametric continuous data.

Results

Out of the 166 students (80 clinical and 86 pre-clinical) contacted for this trial, 109 students participated giving a response rate of 65.6%. The age of students ranged from 21 to 26 years with a mean age of 24.0±0.1.

The majority of students were female (82.6%). Most students (60.0%) were in the seventh year of study (clinical year), and 40.0% were from the fifth year (pre-clinical year). Nearly two-thirds (n = 81; 74.3%) of participants were local, and the rest were international students.

Pre-clinical and clinical students showed no significant differences in opinion regarding having updated knowledge of basic and clinical sciences and clinical competency

(p = 0.889). The student’s perception of their professional skills (p = 0.874) and attitude (p = 0.469)

was not significantly different between the study group years. With regards to the student’s attitude, no significant difference was observed in all given options except patient safety (p < 0.030) [Table 1].

Table 2: Self-reported response on qualities for professionalism in fifth and seventh-year students.

|

Good communication skills |

|

0.434 |

Self-confidence/self-efficacy |

|

0.637 |

|

Yes |

35 (79.5) |

55 (84.6) |

|

Yes |

13 (29.5) |

17 (26.2) |

|

|

No |

9 (20.5) |

10 (15.4) |

|

No |

31 (70.5) |

48 (73.8) |

|

|

Up to date professional knowledge |

|

0.835 |

Logical/critical/creative thinking |

|

0.311 |

|

Yes |

29 (65.9) |

42 (64.6) |

|

Yes |

14 (31.8) |

15 (23.1) |

|

|

No |

15 (34.1) |

23 (35.4) |

|

No |

30 (68.2) |

50 (76.9) |

|

|

Teamwork |

|

|

0.755 |

Lifelong/self-directed learning skills |

|

0.730 |

|

Yes |

21 (47.7) |

33 (50.8) |

|

Yes |

7 (15.9) |

12 (18.5) |

|

|

No |

23 (52.3) |

32 (49.2) |

|

No |

37 (84.1) |

53 (81.5) |

|

|

Integrity/honesty |

|

|

0.824 |

Foreign language skills |

|

|

0.162 |

|

Yes |

16 (36.4) |

25 (38.5) |

|

Yes |

2 (4.5) |

8 (12.3) |

|

|

No |

28 (63.6) |

40 (61.5) |

|

No |

42 (95.5) |

57 (87.7) |

|

|

Respect for others |

|

|

0.752 |

Self-management |

|

|

0.168 |

|

Yes |

15 (34.1) |

24 (36.9) |

|

Yes |

2 (4.5) |

8 (12.3) |

|

|

No |

29 (65.9) |

41 (63.1) |

|

No |

42 (95.5) |

57 (87.7) |

|

|

Ethical thinking and behavior |

|

0.700 |

Appearance/behavior |

|

|

0.940 |

|

Yes |

14 (31.8) |

23 (35.4) |

|

Yes |

4 (9.1) |

6 (9.2) |

|

|

No |

30 (68.2) |

42 (64.6) |

|

No |

40 (90.9) |

59 (90.8) |

|

|

Physical and mental health |

|

0.752 |

Service oriented |

|

|

0.941 |

|

Yes |

15 (34.1) |

24 (36.9) |

|

Yes |

2 (4.5) |

3 (4.6) |

|

|

No |

29 (65.9) |

41 (63.1) |

|

No |

42 (95.5) |

62 (95.4) |

|

|

Patient safety |

|

|

0.029 |

Etiquette |

|

|

0.911 |

|

Yes |

18 (40.9) |

14 (21.5) |

|

Yes |

2 (4.5) |

3 (4.6) |

|

|

No |

26 (59.1) |

51 (78.5) |

|

No |

42 (95.5) |

62 (95.4) |

|

|

Humanity |

|

|

0.342 |

Self-restraint/risk management |

|

0.240 |

|

Yes |

15 (34.1) |

17 (26.2) |

|

Yes |

0 (0.0) |

2 (3.1) |

|

Data presented as n (%).

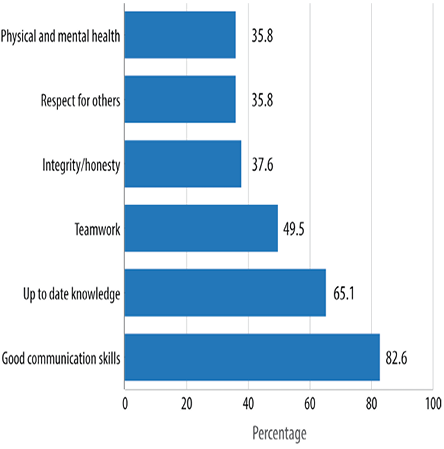

Fifth and seventh-year medical students were asked about qualities they thought were essential for professionalism [Table 2]. The top five qualities essential for professionalism as determined by the students are shown in Figure 1. The top quality was good communication (82.6%). Respect for others (35.8%) and physical and mental health (35.8%) shared the fifth place.

Out of the 110 teaching faculty members contacted for this trial, 83 participated in the study giving a response rate of 75.5%.

Figure 1: The top five qualities essential for professionalism according to medical students.

Their age ranged from 30–57 years with mean age of 41.2±6.7 years. Of the total participants, 43 (51.8%) were female, and 40 (48.2%) were male. Over half (n = 51; 61.4%) were academic general practitioners, 15 (18.1%) were clinical faculty, and 17 (20.5%) were from the basic sciences faculty.

Among participants from the clinical faculty, 22 (26.5%) had fewer than five years experience, 38 (45.8%) had 5–10 years’ experience and 23 (27.7%) had over 10 years’ experience.

The faculty members perception of their professional knowledge and skills is shown in Table 3. A significant statistical difference was observed between clinical and basic sciences faculty members regarding up to date knowledge and clinical competency (p < 0.001). The perception of professional skills between the two faculty groups was not significant (p = 0.094). Study data showed that perception of professional attitude in the basic sciences and clinical faculty group was not significantly different (p = 0.267).

Table 3: Faculty perception of their professional knowledge and skills.

|

Professional knowledge |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I am updated with my knowledge of basic and clinical sciences and clinical competency |

23 (27.7) |

46 (55.4) |

12 (14.5) |

2 (2.4) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Professional skills |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I can do self-management planning for learning |

18 (21.7) |

56 (67.5) |

9 (10.8) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

I am able to do self-restraint/risk management |

10 (12.0) |

57 (68.7) |

16 (19.3) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

My physical health is appropriate |

27 (32.5) |

33 (39.8) |

22 (26.5) |

1 (1.2) |

0 (0.0) |

|

My mental health is appropriate |

37 (44.6) |

39 (47.0) |

7 (8.4) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

I have lifelong learning skills; I can solve problems and make appropriate decisions; self-directed learner |

27 (32.5) |

45 (54.2) |

10 (12.0) |

1 (1.2) |

0 (0.0) |

|

I can do teamwork |

27 (32.5) |

44 (53.0) |

12 (14.5) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

I have good communication skills |

26 (31.3) |

49 (59.0) |

8 (9.6) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

I am comfortable with foreign language skills |

20 (24.1) |

50 (60.2) |

13 (15.7) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

I have creative/logical/critical thinking |

15 (18.1) |

46 (55.4) |

22 (26.5) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Professional attitude |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I understand hospital/clinic setup (service oriented) |

23 (27.7) |

50 (60.2) |

10 (12.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

I have respect for others and self |

47 (56.6) |

31 (37.3) |

5 (6.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

I am a role model |

17 (20.5) |

43 (51.8) |

23 (27.7) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

I have good etiquette/humanity |

33 (39.8) |

42 (50.6) |

8 (9.6) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

I prefer ethical thinking and behavior |

33 (39.8) |

39 (47.0) |

11 (13.3) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

I am self-confident |

19 (22.9) |

55 (66.3) |

9 (10.8) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

I always maintain integrity/honesty |

25 (30.1) |

44 (53.0) |

12 (14.5) |

2 (2.4) |

0 (0.0) |

|

I do regular self-assessment |

23 (27.7) |

36 (43.4) |

19 (22.9) |

5 (6.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

I have appropriate appearance/behavior |

21 (25.3) |

45 (54.2) |

17 (20.5) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

I am fully aware of patient safety |

32 (38.6) |

33 (39.8) |

18 (21.7) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

Data presented as n (%).

Table 4: Self-reported response on qualities for professionalism by clinical and basic sciences faculty members.

|

Up to date knowledge |

|

|

0.001 |

Physical and mental health |

|

0.542 |

|

Yes |

47 (71.2) |

5 (29.4) |

|

Yes |

15 (22.7) |

5 (29.4) |

|

|

No |

19 (28.8) |

12 (70.6) |

|

No |

51 (77.3) |

12 (70.6) |

|

|

Teamwork |

|

|

<0.001 |

Ethical thinking and behavior |

|

0.341 |

|

Yes |

37 (56.1) |

1 (5.9) |

|

Yes |

13 (19.7) |

5 (29.4) |

|

|

No |

29 (43.9) |

16 (94.1) |

|

No |

53 (80.3) |

12 (70.6) |

|

|

Good communication skills |

|

0.016 |

Lifelong/self-directed learning skills |

0.923 |

|

Yes |

33 (50.0) |

3 (17.6) |

|

Yes |

11 (16.7) |

3 (17.6) |

|

|

No |

33 (50.0) |

14 (82.4) |

|

No |

55 (83.3) |

14 (82.4) |

|

|

Patient safety |

|

|

0.019 |

Service oriented |

|

|

0.071 |

|

Yes |

23 (34.8) |

1 (5.9) |

|

Yes |

11 (16.7) |

0 (0.0) |

|

|

No |

43 (65.2) |

16 (94.1) |

|

No |

55 (83.3) |

17 (100.0) |

|

|

Self-management |

|

|

0.002 |

Respect for others |

|

|

0.785 |

|

Yes |

20 (30.3) |

12 (70.6) |

|

Yes |

21 (31.8) |

6 (35.3) |

|

|

No |

46 (69.7) |

5 (29.4) |

|

No |

45 (68.2) |

11 (64.7) |

|

|

Self-restraint/risk management |

|

0.251 |

Self-confidence/self-efficacy |

|

0.091 |

|

Yes |

20 (30.3) |

8 (47.1) |

|

Yes |

10 (15.2) |

7 (41.2) |

|

|

No |

46 (69.7) |

9 (52.9) |

|

No |

56 (84.8) |

10 (58.8) |

|

|

Humanity |

|

|

0.353 |

Appearance/behavior |

|

0.426 |

|

Yes |

19 (28.8) |

3 (17.6) |

|

Yes |

7 (10.6) |

3 (17.6) |

|

|

No |

47 (71.2) |

14 (82.4) |

|

No |

59 (89.4) |

14 (82.4) |

|

|

Integrity/honesty |

|

|

0.164 |

Etiquette |

|

|

0.003 |

|

Yes |

16 (24.2) |

7 (41.2) |

|

Yes |

5 (7.6) |

6 (35.3) |

|

|

No |

50 (75.8) |

10 (58.8) |

|

No |

61 (92.4) |

11 (64.7) |

|

|

Logical/critical/creative thinking |

|

0.164 |

Foreign language skills |

|

0.210 |

|

Yes |

16 (24.2) |

7 (41.2) |

|

Yes |

5 (7.6) |

3 (17.6) |

|

Data presented as n (%).

Table 5: Comparison between faculty and students on their self-reported response on items of professionalism.

|

Good communication skills |

|

<0.001 |

Patient safety |

|

|

0.947 |

|

Yes |

36 (43.4) |

90 (82.6) |

|

Yes |

24 (28.9) |

32 (29.4) |

|

|

No |

47 (56.6) |

19 (17.4) |

|

No |

59 (71.1) |

77 (70.6) |

|

|

Up to date knowledge |

|

|

0.722 |

Humanity |

|

|

0.663 |

|

Yes |

52 (62.7) |

71 (65.1) |

|

Yes |

22 (26.5) |

32 (29.4) |

|

|

No |

31 (37.3) |

38 (34.9) |

|

No |

61 (73.5) |

77 (70.6) |

|

|

Teamwork |

|

|

0.606 |

Logical/critical/creative thinking |

|

0.864 |

|

Yes |

38 (45.8) |

54 (49.5) |

|

Yes |

23 (27.7) |

29 (26.6) |

|

|

No |

45 (54.2) |

55 (50.5) |

|

No |

60 (72.3) |

80 (73.4) |

|

|

Respect for others |

|

|

0.639 |

Self-confidence/self-efficacy |

|

0.261 |

|

Yes |

27 (32.5) |

39 (35.8) |

|

Yes |

17 (20.5) |

30 (27.5) |

|

|

No |

56 (67.5) |

70 (64.2) |

|

No |

66 (79.5) |

79 (72.5) |

|

|

Integrity/honesty |

|

|

0.149 |

Lifelong/self-directed learning skills |

0.918 |

|

Yes |

23 (27.7) |

41 (37.6) |

|

Yes |

14 (16.4) |

19 (17.4) |

|

|

No |

60 (72.3) |

68 (62.4) |

|

No |

69 (83.1) |

90 (82.6) |

|

|

Physical and mental health |

|

0.082 |

Etiquette |

|

|

0.031 |

|

Yes |

20 (24.1) |

39 (35.8) |

|

Yes |

11 (13.3) |

5 (4.6) |

|

|

No |

63 (75.9) |

70 (64.2) |

|

No |

72 (86.7) |

104 (95.4) |

|

|

Self-management |

|

|

<0.001 |

Foreign language skills |

|

|

0.913 |

|

Yes |

32 (38.6) |

10 (9.2) |

|

Yes |

8 (9.6) |

10 (9.2) |

|

|

No |

51 (61.4) |

99 (90.8) |

|

No |

75 (90.4) |

99 (90.8) |

|

|

Self-restraint/risk management |

|

<0.001 |

Service oriented |

|

|

0.031 |

|

Yes |

28 (33.7) |

2 (1.8) |

|

Yes |

11 (13.3) |

5 (4.6) |

|

|

No |

55 (66.3) |

107 (98.2) |

|

No |

72 (86.7) |

104 (95.4) |

|

|

Ethical thinking and behavior |

|

0.063 |

Appearance/behavior |

|

|

0.518 |

|

Yes |

18 (21.7) |

37 (33.9) |

|

Yes |

10 (12.0) |

10 (9.2) |

|

Data presented as n (%).

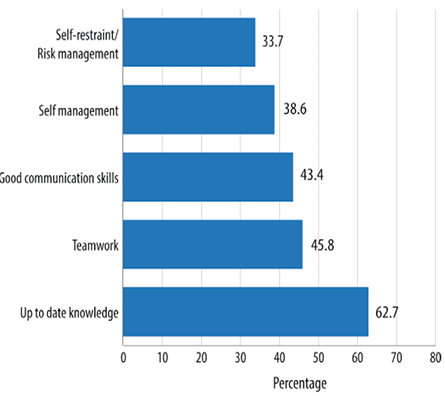

Clinical and basic sciences faculty members were also asked about the qualities they believed to be essential for professionalism [Table 4]. They answered yes/no questions to determine the attributes they believed to be essential for professionalism. Sixty-two percent thought that up to date professional knowledge was an essential attribute [Figure 2]. We observed a statistically significant difference in gender with regard to logical/critical/creative thinking (p = 0.031), integrity/honesty (p = 0.055), and ethical thinking and behavior (p = 0.014) professional qualities.

Figure 2: The top five qualities of practice or skills essential for professionalism according to faculty members.

Students and faculty members had a significant difference in opinion regarding up to date knowledge of basic and clinical sciences and clinical competency (p = 0.024). Similarly, the perception of professional skills (p = 0.001) and attitude (p = 0.001) was significantly different between the two student year groups.

In Table 5, we compared the responses of faculty members and students to attributes they believed to be essential for professionalism.

Discussion

Professionalism is a critical quality needed by physicians to provide competent and compassionate care to patients. It encompasses a set of values and behaviors that underpin the social contract between the public and the medical profession.15 Physicians should uphold the highest standards of ethical and professional behavior in all their actions and activities, the practice of medicine involves trust between the patient and their doctor.

In our study, most students agreed that up to date knowledge is an important attribute. Students felt positive about their professional skills but did not feel comfortable with their foreign language proficiency and self-management. Developing reflective skills were related to student’s comfort with multi-tasking and self-directed learning, which helps to develop positive attitude in professionalism.16 Medical students perception of professionalism suggests that our current generation of learners may have a different perception of professionalism as it relates to specific behaviors. This raises the importance for teachers to clearly identify and make explicit the expectations of medical students as they interact in classroom and clinical settings.17

Two-thirds of students expressed that they see themselves as role models for others in professional attitude and communication. The literature has reported that students identify the need for strong positive role models in their learning environment for effective evaluation of professionalism.18 A recent publication suggested that role modeling is an untapped educational resource that should be emphasized in faculty development initiatives.19

Although medical students expressed a positive attitude towards professionalism, they felt that ethical thinking and behavior was not a part of professionalism. One-third of students felt that they were not confident and that their self-assessment and knowledge reflection was not appropriate. Ginsburg et al,20,21 showed that behavior is contextual that the student’s and the evaluator’s perception often determine whether the unprofessional behavior is recorded or reported. There is no formal teaching of professionalism in the curriculum; however, there is continuous assessment and examinations such as clinical encounter and objective structured clinical examination (OSCE). Encouraging students to experience this sense of responsibility for one another at an early stage may help build teamworking skills and reduce destructive competition.22 This poses a great challenge as to how we can teach and assess this attribute in the medical curriculum. Cruess23 described the need for the explicit teaching of the definition and values of professionalism and that institutional leadership and support is needed to demonstrate its fundamental significance. Teaching and assessing professionalism makes student aware of its importance in clinical practice.24

Faculty were very positive about professionalism in up to date knowledge and competency. However, there was a significant difference between basic science and clinical faculty regarding teamwork, self-restraint, self-management, patient safety, and communication skills. Teachers in the health profession stimulate intrinsic motivation (motivation that stems not from external factors, such as grades and status, but from genuine interest and ambition) in their students and professionalism can be learned through practice and self-reflection on teaching practices and measuring the right behavior.25 Faculty and students agreed that the top qualities of professionalism were up to date knowledge, teamwork, and good communication skills. There was no statistically significant difference in good communication skills, self-management, and self-restraint/risk management between faculty and students. The literature also supports that encouraging participation and strengthening self-efficacy may help to enhance medical student performance and further motivation in learning strategies.26

Medical teachers need to encourage their students to elevate their professionalism. Our study population is well aware of this, and there is a consensus on a few attributes. Personal and environmental factors play an important role in the development of professionalism.27 One study showed that the core elements of professionalism can be taught but may not be fully assimilated by students, and student’s perception in their first year of medical school might be different.28 Professionalism as a whole is beneficial in patient care for all healthcare professionals. This should be seen as a necessary process to preserve and enhance our ability to meet the needs of our patients.29,30 Teaching and learning professionalism is an integral part of medical education. Assessment at all levels is mandatory for feedback, improvement, and to establish positive attributes in medical students.31,32

The sample size in this study limits the ability to generalize the results. However, some interesting trends highlight the need for further research. There are some agreements and some differences between students and faculty response, so further research is essential to determine the cause of such perceptional differences.

Conclusion

Certain aspects of professionalism seem to be underdeveloped in medical students. To improve recognition of the relationship of physician self-care to the ability to care for patients, we need to recognize that personal and organizational factors influence the professionalism of individual physicians. These aspects of professionalism may need to be targeted for teaching and assessment so that students develop as professionally responsible practitioners. Students with a well-developed understanding of professionalism may be less involved in medical error and have the personal values to help them deal with error honestly and effectively.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this study.

references

- Swick HM. Toward a normative definition of medical professionalism. Acad Med 2000 Jun;75(6):612-616.

- Hilton SR, Slotnick HB. Proto-professionalism: how professionalisation occurs across the continuum of medical education. Med Educ 2005 Jan;39(1):58-65.

- General Medical Council. Tomorrow’s Doctors: Outcomes and standards for undergraduate medical education. London: GMC, 2009. [Cited April 2015]. Available form: http://www.gmc-uk.org/Tomorrow_s_Doctors_1214.pdf_48905759.pdf

- ABIM Foundation. American Board of Internal Medicine; ACP-ASIM Foundation. American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine; European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med 2002 Feb;136(3):243-246.

- Reiser SJ, Banner RS. The Charter on Medical Professionalism and the limits of medical power. Ann Intern Med 2003 May;138(10):844-846.

- Shrank WH, Reed VA, Jernstedt GC. Fostering professionalism in medical education: a call for improved assessment and meaningful incentives. J Gen Intern Med 2004 Aug;19(8):887-892.

- Swick H, Szenas P, Danoff D, Whitcomb M. Teaching professionalism in undergraduate medical education. JAMA1999;282: 830–2.

- Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA 2002 Jan;287(2):226-235.

- Kao A, Lim M, Spevick J, Barzansky B. Teaching and evaluating students’ professionalism in US medical schools, 2002-2003. JAMA 2003 Sep;290(9):1151-1152.

- Hatem CJ. Teaching approaches that reflect and promote professionalism. Acad Med 2003 Jul;78(7):709-713.

- Stephenson A, Higgs R, Sugarman J. Teaching professional development in medical schools. Lancet 2001 Mar;357(9259):867-870.

- Whitcomb ME. Medical professionalism: can it be taught? Acad Med 2005 Oct;80(10):883-884.

- Coulehan J. Viewpoint: today’s professionalism: engaging the mind but not the heart. Acad Med 2005 Oct;80(10):892-898.

- Arnold L. Assessing professional behavior: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Acad Med 2002 Jun;77(6):502-515.

- Henderson P, Johnson M. An innovative approach to developing the reflective skills of medical students. In: BMC Medical Education.2002.

- Adkoli BV, Al-Umran KU, Al-Sheikh M, Deepak KK, Al-Rubaish AM. Medical students’ perception of professionalism: a qualitative study from Saudi Arabia. Med Teach 2011;33(10):840-845.

- Byszewski A, Hendelman W, McGuinty C, Moineau G. Wanted: role models–medical students’ perceptions of professionalism. BMC Med Educ 2012;12:115.

- Kenny NP, Mann KV, MacLeod H. Role modeling in physicians’ professional formation: reconsidering an essential but untapped educational strategy. Acad Med 2003 Dec;78(12):1203-1210.

- Ginsburg S, Regehr G, Hatala R, McNaughton N, Frohna A, Hodges B, et al. Context, conflict, and resolution: a new conceptual framework for evaluating professionalism. Acad Med 2000 Oct;75(10)(Suppl):S6-S11.

- Ginsburg S, Regehr G, Lingard L. The disavowed curriculum: understanding student’s reasoning in professionally challenging situations. J Gen Intern Med 2003 Dec;18(12):1015-1022.

- Ginsburg S, Regehr G, Lingard L. Basing the evaluation of professionalism on observable behaviors: a cautionary tale. Acad Med 2004 Oct;79(10)(Suppl):S1-S4.

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Johnston SE. Professionalism: an ideal to be sustained. Lancet 2000 Jul;356(9224):156-159.

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Teaching professionalism: general principles. Med Teach 2006 May;28(3):205-208.

- Ainsworth MA, Szauter KM. Medical student professionalism: are we measuring the right behaviors? A comparison of professional lapses by students and physicians. Acad Med 2006 Oct;81(10)(Suppl):S83-S86.

- West CP, Shanafelt TD. The influence of personal and environmental factors on professionalism in medical education. BMC Med Educ 2007;7:29.

- Stegers-Jager KM, Cohen-Schotanus J, Themmen AP. Motivation, learning strategies, participation and medical school performance. Med Educ 2012 Jul;46(7):678-688.

- Yera H. Core Elements of Medical Professionalism for Medical School Applicants. Korean J Med Educ 2006 Dec;18(3):297-307.

- Mann KV, Ruedy J, Millar N, Andreou P. Achievement of non-cognitive goals of undergraduate medical education: perceptions of medical students, residents, faculty and other health professionals. Med Educ 2005 Jan;39(1):40-48.

- Hur Y. Are There Gaps between Medical Students and Professors in the Perception of Students’ Professionalism Level? Yonsei Med J 2009;50(6):751-756.

- Lynch DC, Surdyk PM, Eiser AR. Assessing professionalism: a review of the literature. Med Teach 2004 Jun;26(4):366-373.

- Huddle TS; Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Viewpoint: teaching professionalism: is medical morality a competency? Acad Med 2005 Oct;80(10):885-891.

- Howe A. Professional development in undergraduate medical curricula–the key to the door of a new culture? Med Educ 2002 Apr;36(4):353-359.