Tobacco use is the world’s leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality, and has been classified as a global epidemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Bank.1,2 The WHO estimates that tobacco use kills nearly six million people annually, including the 600 000 who are killed by exposure to second-hand smoke (SHS).3 Nearly 80% of the world’s smokers live in low- and middle-income countries.1 Unchecked, tobacco-related deaths will increase to more than eight million per year by 2030 with more than 80% of those deaths occurring in such countries.1

Tobacco use in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, which encompasses many Arab countries including Oman, remains one of the greatest challenges facing public health. This region is one of the two regions with the fastest growing consumers of tobacco products and where the prevalence is expected to increase 25% by the year 2025, compared to a decrease in Asia, America, and Europe.4 The prevalence of tobacco use among Omani men aged ≥ 15 years old was estimated to be 17.9% in 2010.4 It is predicted to increase to 21.4%, 26.9%, and 33.3% in 2015, 2020, and 2025, respectively, if tobacco control measures remain static.4 This figure, the lowest in the region and half of the regional average (36.8%), contrasts sharply compared to other countries in the region which have some of the highest prevalence globally, such as Iran (30.2%), Lebanon (45.4%), Bahrain (48.8%), and Egypt (49.9%).4,5

In 2005, Oman became party to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control6 (hereafter referred to as the Convention), an international treaty that sets out numerous obligations aimed to reduce the global burden of tobacco use. During its annual meeting in May 2013, the World Health Assembly endorsed the Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020 and adopted a comprehensive global monitoring framework with nine voluntary targets for 2025.7 One target, endorsed by Oman, is a 30% relative reduction in the prevalence of current tobacco use in persons aged ≥ 15 by 2025.7

In this review, we provide a descriptive analysis of the evolution of tobacco control policies in Oman in relation to the country’s international obligations and recommend policy options that, if followed, will likely lead Oman to achieve the 2025 target.

Tobacco control in Oman

Before 1970, Oman was known as “Muscat and Oman” and was governed by H.M. Sultan Sa’id bin Taimur Al-Said for four decades (1932–1970). During this period, smoking in all indoor and outdoor public places was banned8,9 and enforced by public flogging and jail sentences.10 By July 1970, Sultan Qaboos bin Sa’id acceded to power and these restrictions were relaxed. As put by Sergey Plekhanov: “smokers spilled out into the streets, saluting with clouds of smoke the abolition of the law of smoking outdoors”.11 He continued: “the glow of cigarettes stretched in an unbroken chain along the road of Matrah”.11

Tobacco control started in Oman in the 1980s, but never returned to the heavy-handed measures of the early twentieth century. The introduction of regulatory measures were overseen by a national committee tasked to address the increasing prevalence of smoking. It worked closely with a committee established by the Health Ministers’ for the Gulf Corporation Council (GCC), which includes six member states (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates).

We have used the WHO’s 6-points MPOWER initiative12 to examine progress made in Oman on Monitoring the epidemic, Protecting people from SHS, Offering cessation services to tobacco users, Warning the public about the dangers of tobacco, Enforcing a ban on advertising, promotion and sponsorship, and Raising taxes and prices of all tobacco products. The initiative is a package of policies and interventions to guide countries in implementing the measures of the Convention. These strategies are extracted from the Convention as six effective demand reduction measures and have shown success when implemented fully. In addition, it stresses the importance of surveillance, monitoring, and evaluation to measure the impact of tobacco control strategies and adjust as needed.13

Monitor tobacco use and prevention policies

Article 20 of the Convention states that parties should establish surveillance systems to monitor the magnitude, patterns, determinants, and consequences of tobacco consumption and exposure.6 It is only with accurate data that policy makers can identify appropriate interventions to implement and measure their impact. Thus, surveillance systems need to use standardized and scientifically sound methods. Surveys need to be conducted regularly (no more than five years apart) to obtain comparable data over time.13

Although Oman does not have an established formal tobacco surveillance system, current data show tobacco use in adults to be relatively low (4.6%) compared to many developing countries [Table 1]. The prevalence in 2008 was significantly higher in men (9.7%) than women (0.1%). A similar pattern was also reported in 2000 (8.7% in men and 0.1% in women). Although cigarette use was lower (1.8%) among adolescents (aged 13–15 years), its prevalence was higher among college students (9.9%; mean age 25 years). The use of smokeless tobacco (SLT) in youth aged 13–15 years surged between 2007 and 2010 while cigarettes and waterpipes dropped [Table 1]. Twice as many boys used SLT as girls.

Table 1: Prevalence of tobacco use in surveys conducted in Oman between 2007–2010.

|

Adults, National surveys |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Family Health Survey, 199514 |

|

13.2 |

0.2 |

6.7 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

National Health Survey, 200015 |

15+ (9 461) |

8.7 |

0.1 |

4.4 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

World Health Survey, 200816 |

18+ (3 345) |

9.7 |

0.1 |

4.6 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Adults, Regional surveys |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nizwa Healthy Lifestyle Project Survey, 200117 |

20+ (1 511) |

9.6 |

0 |

3.5 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Sur Healthy Lifestyle Survey, 200618 |

20+ (1 373) |

20.9 |

0.4 |

9.3 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Evaluation of the Nizwa Healthy Lifestyle Project Survey, 201019 |

20+ (1 976) |

5.3 |

0 |

2.3 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Young Adults |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

College Students KAP Survey, 2008 |

Mean 20.5 (3 473) |

17.4

13.8–21.8 |

1.5

0.8–2.9 |

9.9

7.7–12.7 |

13.2

8.6–19.9 |

1.2

0.5–2.8 |

7.7

4.9–11.9 |

7.0

3.9–12.2 |

0.4

0.2–0.9 |

3.9

2.1–7.0 |

|

Global Health Professional Survey, 2010

3rd year students |

N/A (880) |

7.3

3.6–11.0 |

0.8

0.3–1.2 |

2.3

1.7–2.9 |

5.2

1.7–8.6 |

0.8

0.3–1.2 |

1.8

1.1–2.6 |

6.9

2.0–11.8 |

4.3

2.9–5.6 |

5.0

2.9–7.1 |

|

Adolescents |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Global Youth Tobacco Survey, 200720 |

13–15

(2 297) |

3.5

1.8–6.6 |

1.2

0.3–4.1 |

2.3

1.1–4.8 |

4.3

2.3–8.0 |

1.4

0.6–3.5 |

3.1

1.6–5.6 |

5.3

3.1–8.9 |

2.3

1.0–4.9 |

4.1

2.5–6.8 |

All numbers are percentages (%) unless otherwise stated, ranges are 95% confidence intervals; N/A not available.

Protect people from second-hand smoke

Article 8 of the Convention states that there should be effective legislative, executive, administrative and/or other measures established to protect people from exposure to SHS in indoor workplaces, public transport, indoor public places and, as appropriate, other public places.6 WHO recommends that all smoke-free laws ensure complete (100%) smoke-free environments, without designated smoking areas (DSA) or smoking-rooms.12

Over the past three decades, regulations establishing smoke-free public places in Oman have evolved gradually but were limited to public buildings. The Ministry of Health was the first to implement a smoke-free building policy in 1993.22 This was followed a year later by instructions of the Cabinet of Ministers’ to all heads of government units to implement a smoke-free building policy.23 Smoking was officially banned in all government schools in Oman in 2001 although smoking was not permitted in all educational premises since the early 1970s.24 Although a ban on domestic flights and flights to all GCC countries was in effect since 1998 when regional carriers implemented a similar policy, Oman Air, the national airline, banned smoking on international flights beyond GCC countries only in April 2001.25 In 2005, the Oman Airports Management Company banned smoking in all airport buildings in the country while designating a lounge for smokers.26 Private sector institutions, including private schools, were not subjected to smoke-free laws until 2008 although some of the former and all of the latter were smoke-free long before the official ban.

In 2009, a substantial smoking ban for all enclosed public spaces was issued by Muscat Municipality (MM), which in addition to most of the above, included bars and hotel lobbies. Other regional jurisdictions (under the Ministry of Regional Municipalities and Dhofar Municipality in 2010 and Sohar Municipality in 2011) soon followed suit. Although this piecemeal effort may not be as strong as a national comprehensive tobacco legislation, evidence indicates that adherence to smoking bans in public places is high.27,28

The ban on smoking in public places throughout the country presented significant progress for tobacco control in Oman. However, it falls short of the recommendations for two reasons. First, it allows DSA within enclosed public spaces. However, the stringent and complex technical requirements to establish DSA,29 including the condition that the total area of the premises should be not less than 100 m2 might have deterred many businesses from requesting permits for DSA and may explain why only seven requests for permits were submitted between 2010 and 2014 in the Muscat area (Health Administration of MM, verbal communication).

Second is a lack of enforcement of the law for waterpipe cafes, which largely stems from a historical precedent set by a court ruling regarding these cafes. In March 2001, MM issued a decision banning all cafes in Muscat governorate from serving waterpipes to customers as part of “a mission to preserve the behavior and appearance of general civilization and to fight against a strange and unhealthy phenomena”.30 Some cafes challenged this decision in the Administrative Court on the basis that it is not within the jurisdiction of MM to issue such a ban. In May 2001, the Court concurred with the Municipality’s decision since public health protection was within the mandate of MM. However, the Court also concurred with complainants in seeking compensation and ordered the appointment of a financial expert to review compensation claims for cafes who they claimed had spent significant financial resources on preparing their cafes to serve waterpipes. Subsequently, the two parties came to a mutual understanding, where enforcing the ban on serving waterpipes was halted and no compensations were awarded. Subsequent attempts by health authorities to convince the municipalities to implement a total smoking ban in indoor areas in waterpipe cafes have gone in vain.

Offer tobacco cessation service

Article 14 of the Convention stipulates that parties should address tobacco dependence by promoting services for the cessation of tobacco use.6 Two main interventions include counselling through regular health services and telephone quit lines and access to pharmacological therapy.

At present, the Health Ministry does not offer formal cessation services to smokers. However, two cessation clinics were established by individual physicians in primary health care settings in Muscat and Nizwa in 2006 and 2009, respectively. A third clinic was established in the primary health care center at the main public university in Muscat in 2015. Such cessations clinics offered nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) patches and gums for two to four months. They also provided psychological therapy (basic counseling, motivational interviewing, and cognitive behavioral therapy). Some large private companies also provide cessation services to their employees, mostly limited to NRT. Despite these ad hoc initiatives, no plans exist to offer cessation services as a routine part of health services

delivery nationwide.

Although NRT is widely available as an over the counter medication in local pharmacies, most pharmacist lack appropriate training and are unable to provide proper advice to NRT users.

Warn about the dangers of tobacco use

Warning people about the dangers of tobacco use is covered in Articles 11 and 12 of the Convention.6 Details about the packaging and labeling of tobacco products are outlined in Article 11 where parties are expected to ensure that product packaging and labelling do not promote a tobacco product including creating an impression that a specific product is less harmful by using terms like “light” or “mild”.6 It also states that each package must have a health warning about the harmful effects of tobacco use. Pictorial health warnings (PHW) are a cost-effective way to raise awareness of the dangers of tobacco use. Article 12 describes the parties’ obligations to promote public awareness of tobacco control issues.6 The MPOWER package describes three interventions including product-warning labels; educating the public about the health risks of tobacco use; and media coverage of tobacco control activities.

In 1986, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry (MOCI) of Oman informed all tobacco products importers that no such products will be permitted to enter the country without the following textual health warnings: “Smoking is the leading cause of cancer, lung, heart, and arterial diseases.”31 This was required on the front of the pack in both Arabic and English languages and in clear font. The circular also mandated that the “Government Warning,” which was in use on some tobacco products, be changed to “Health Warning”. However, these specifications did not outline the position, size, or color of fonts to be displayed in relation to the cigarette pack. This was left at the discretion of the tobacco manufacturers.

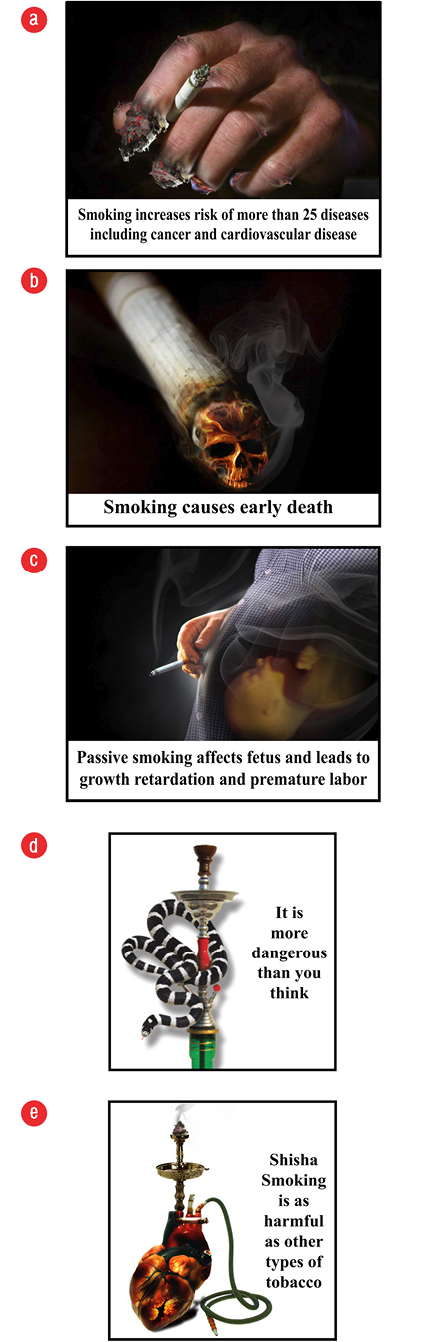

By 2009, the first standard specifications for this technical regulation were put forward to the governing body of the Gulf Standardization Organization for approval. In August 2011, the technical regulations for three PHW for cigarettes and two for waterpipe tobacco products were approved for implementation starting in August 2012 [Figure 1].32 These regulations required that the size of the health warning on the pack be no less than 50% of the front (in Arabic) and 50% of the back (in English) of the lower part of the principle display areas. The size of the text to be 40% within the 50% of pack surface area.

Figure 1: (a, b, and c) Pictorial health warnings for cigarettes and (d and e) waterpipe tobacco products adopted by GCC states in 2012.

Numerous awareness activities have taken place at the national, regional, and institutional level by the Ministry of Health as well as with other institutions including schools and colleges, many of which are covered by the mass media. Awareness of the harms of tobacco is high. For example, a large percentage of young people aged 13–15 years think that smoking cigarettes and waterpipes and using SLT is harmful (84.3%, 93.7%, 89.0%, respectively), and a similar proportion recognize the hazards of SHS (72.8% for cigarettes and 84.2% for waterpipes).21 These negative perceptions are possibly a reflection of societal attitudes and mass media efforts rather than schooling since 83.9% reported seeing anti-tobacco media messages but only two-thirds of young people aged 13–15 years reported that they were taught the dangers of smoking.21

Enforce bans on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship

A comprehensive ban on advertising, promotion, and sponsorship of tobacco products is covered in Article 13 of the Convention.6 Such bans are highly effective in reducing tobacco use among all income and educational levels.33 They include bans on advertising in all types of media, restrictions on marketing by importers and retailers, and restrictions on promotional and sponsorship activities in the sport and entertainment industry such as the provision of incentives that encourage the purchase of tobacco products.

Cigarette advertisement was rampant in Oman in the early 1970s and continued into the early 2000s [Figure 2]. However, close cooperation between members of the National Tobacco Control Committee (NTCC) members (including Ministry of Information, MOCI, and the local Municipalities) resulted in an “unofficial” ban on all forms of tobacco product advertisements including billboards, national newspapers, locally owned private and public radios, and national televisions broadcasts. This was achieved by the relevant sectors not issuing the required permits necessary for such commercial activities. This informal ban was strictly adhered to by all media companies operating in Oman. However, two forms of advertisement not covered in this unofficial ban were the point-of-sale advertisements (POSA) and those placed on individual tobacco packs.

Figure 2: Aggressive cigarettes advertisement in a supermarket in Oman in the early 2000s.

In April 2016, the regulations governing the Law of Printing and Publishing were amended to include a ban on placing tobacco products advertisement in all forms of media, including electronic media. It is hoped that this development will lead to the implementation of a comprehensive tobacco advertisement ban including POSA. Despite this achievement, tobacco advertisement remains a concern as international media are readily accessible in the country, which do not fall under national jurisdiction and may explain why two in three young people still report seeing cigarette advertisements.21

Restrictions on tobacco promotion and sponsorship are also recent. In 2013, the MOCI amended the products promotion regulations by officially banning “direct or indirect tobacco products promotion”.34 Similar amendments were made to the administrative decision regulating discounts offered on various commercial products to consumers where “direct or indirect discounts on tobacco products” were also banned.35 However, further legislative work is required to restrict sponsorship activities, which is currently banned through mutual understanding between the NTCC and various institutions, which are often targeted by the industry. Research is needed to see if these bans have led to a decrease in the proportion of young people owning an object with a cigarette brand logo (10.5% in 2010) or having been offered free cigarettes by a tobacco company representative (7.3% in 2010).21

Raise taxes on tobacco products

Price and tax measures are effective in reducing tobacco consumption, especially in young people.13 Article 6 of the Convention, encourages parties to adopt tax and price policies including restricting sales and importations of tax- and duty-free tobacco products to control tobacco use.6 Evidence shows that higher prices reduce the number of tobacco users, especially among young people and the poor.13

Tobacco products in Oman and other GCC countries are among the most affordable in the world [Table 2]; ranging between international dollars (I$) 1.90 (after adjusting for purchasing power parity) in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) to I$ 3.42 in Oman compared to I$ 13.18 in the United Kingdom.12 The percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita required to purchase 100 packs of the most sold brand is only 1.08% in Oman compared to 2.53% in Australia, 2.9% United Kingdom, 3.35% in Egypt, 3.6% in Turkey, and 7.87% in Yemen [Table 2].12 The high affordability in Oman and other GCC states is largely due to low levels of custom duties levied (21.1% of retail price) and the total absence of any domestic taxes on tobacco products compared to taxes exceeding 82% of retail price in Turkey and the United Kingdom.12 Classically, all imported consumer goods to Oman are subject to import custom duties at the rate of 5% (ad valorem) of the cost, insurance and freight (CIF) price. Currently, taxes imposed on tobacco products are also in the form of import custom duties levied at the point of entry, and there are no other local/domestic/internal taxes on tobacco products. The first time higher duties (30% of CIF instead of 5%) were levied specifically on tobacco products was in 1980. It was raised again to 50% in 1987 and to 100% of the CIF price in 1999.36 In 2003, Oman and other GCC states contracted a Customs Union Agreement for import duties to 100% of the CIF price (ad valorem) on all tobacco products or a minimum specific duty as per pre-defined schedules and whichever higher is collected (e.g., 100% of CIF price or US$ 26 per 1 000 cigarettes). In September 2016, the minimum specific taxes were raised to US$ 52 per 1 000 cigarettes. A similar increase was imposed on other forms of tobacco products.

Table 2: Affordability of tobacco products in Oman compared to other developing and developed countries using a pack of 20-cigarettes.

|

Oman |

2.84 |

1.58 |

1.08 |

21.1 |

|

Bahrain |

3.42 |

1.71 |

0.47 |

21.1 |

|

Kuwait |

2.34 |

0.84 |

0.59 |

21.1 |

|

Qatar |

2.76 |

0.83 |

0.29 |

21.1 |

|

Saudi |

3.42 |

N/A |

1.05 |

21.1 |

|

UAE |

1.90 |

0.57 |

0.61 |

21.1 |

|

Egypt |

5.79 |

2.31 |

3.35 |

71.47 |

|

Iran |

8.81 |

1.32 |

1.62 |

17.33 |

|

Yemen |

2.05 |

0.68 |

7.87 |

52.88 |

|

Australia |

11.96 |

9.44 |

2.53 |

63.10 |

|

Turkey |

7.02 |

3.86 |

3.6 |

82.1 |

Figures are taken from reference.12 *The higher the percentage, the less affordable.

Source: Prices of premium and cheapest brands as well as data on percentage of GDP per capita required to purchase 100 packs of most sold brand are from reference 12. UAE: United Arab Emirates; UK: United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Figures in the table do not incorporate the latest increase in taxes and prices in 2016.

In May 2016, the Committee on Financial and Economic Cooperation of the GCC states amended the specific excise tax on tobacco products, making it equivalent to twice the current minimum applied on all tobacco products and its derivatives, starting 1 September 2016.37

Despite what appears as “high duty rates” (100% of the CIF), custom duties when measured as a percentage of the retail price (PRP), are in fact very low and account for just (22%) of the retail price. Even after the new excise tax was imposed in September 2016, the proportion of tax/pack was 44% of the PRP (if pack price did not increase) and lower than 44% if the tobacco industry decides to increase the pack price. The WHO recommends taxes to be no less than 70% of the retail price.38

There are several obstacles to raising custom duties on tobacco products in Oman. Multilateral and bilateral trade agreements constrain Oman as well as other GCC countries from raising custom tariffs on cigarettes and other tobacco products thereby restricting the country’s ability to raise prices to reduce tobacco consumption and smoking incidence/prevalence while increasing government revenue from tobacco taxation.39 Oman joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2000 and has to comply with a maximum import duty known as the “bound rate”. For tobacco products the bound rate is set to 150% of the CIF price. However, currently it is levied at the rate of 100% of import duty across the GCC which is set at the “bound rate” for both Bahrain and Kuwait.39 Furthermore, a bilateral free trade agreement between Oman and the United States (US) dictates that Oman removes tariffs on cigarettes (among other products) within a 10-year period (due by 2018).40 As a result, current custom tariffs on tobacco products imported from the US will be lifted in 2018. Thus, raising import duties on tobacco products is impossible for Oman and other GCC states.

Tobacco cultivation

Tobacco leaf (Nicotiana tabacum), locally known as Ghaliyoon, Dukhyan, Tambak, and Tabac,41 is grown in Oman in limited areas and confined to six out of 61 administrative regions.42 According to the Agricultural Census of 2012/2013, the total area utilised for tobacco cultivation is less than 450 acres with an annual yield of 1 800 metric tons of dry tobacco leaf.42 Each ton of dry leaf tobacco is sold at US$ 3 250 with the annual revenue of US$ 5.8 million from cultivated tobacco in Oman. Most of the cultivated tobacco is exported to countries of the GCC in the form of unmanufactured tobacco/stripped leaf.43 About 70% is exported to Saudi Arabia, 15% to Bahrain, and the rest to other GCC countries and Iran.43 The Convention requires countries to promote economically viable alternatives for tobacco farmers. Thus, despite the small production levels, consideration should be made to gradually replace tobacco cultivation in Oman.

Tobacco trade

Currently, there are no tobacco products manufacturing facilities in Oman. Almost all tobacco products used or sold in the country are imported. Over 80% of tobacco products entering Oman are imported from the UAE followed by Germany (9%), Switzerland (2.5%), Poland (2.3%), and Turkey (1.5).43 About 98% of imported tobacco products are re-exported to Iran.43,44 Oman’s tobacco imports have increased from US$ 48.9 million in 2008 to US$ 116.4 million in 2010. Cigarettes are one of the top 10 imported products in Oman and tobacco exports have tripled in recent years (US$ 21 million in 2008 to US$ 78 million in 2010).45

A few measures implemented in Oman have been made to control the tobacco trade. For example, the sale of all forms of tobacco products to minors as well as sale of individual cigarette sticks were banned in 2001.46 An official ban was placed on all forms of SLT imports and sales in 2010 followed by a ban on its circulation in the country in 2015.47,48 Given that 7.3% of young people aged 13–15 years have been offered a free cigarette from a cigarette representative, strengthening enforcement measures is required.

Illicit trade in tobacco products

The illicit cigarette trade deprives governments of tax revenue and increases tobacco-related deaths. Cigarettes are a particularly attractive product to smugglers because tax is a high proportion of price, and evading tax by diverting tobacco products into the illicit market (where sales are largely tax-free) generates a considerable profit margin for smugglers.49 Data from the Customs Department of the Royal Oman Police show that illicit trade seizures increased from 5.1 million sticks in 2011 to 7.2 million in 2012, and 34 million in 2013. The market values these seizures from US$ 127 to 187 thousand. However, it is estimated that smuggling counterfeit cigarettes in Oman leads to a revenue loss of at least US$ 9.1 million.45 Oman is not yet party to the Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products.

The tobacco industry in Oman

Since the early 1970s, the tobacco industry has formed various organised groups to subvert tobacco control activities in Oman. They initially setup the Middle East Working Group (MEWG) between 1970 to 1988, which later became the Middle East Tobacco Association (META).50 The latter was a conglomerate of six transnational tobacco companies (TTC) based in Dubai’s free-trade zone of Jabel Ali in the UAE50 with a country-specific taskforce, the Oman Working Group (OWG), working in the country.51 Both META and OWG closely monitored government policies that addressed tobacco control as well as local anti-tobacco activists and decision makers in relevant ministries of the Omani Government (including ministers, undersecretaries, and custom officials). They implemented several strategies to counter the country’s efforts in tobacco control. An internal tobacco industry document stresses the need to “re-emphasise the counterproductive nature of any tax increase and to deter the authorities from taking this step”.51 The same document stated that “greater restrictions on public smoking as an imminent future threat” to the industry.51 Evidence also indicates that their efforts resulted in watered-down and delayed implementation of WHO recommended PHW on cigarette packs and a longer grace period (over 12 months) to rid old stock and to comply with newer packing regulations and standards.52

To improve their corporate image, the tobacco industry also conducted several corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities making financial contributions to society’s most vulnerable groups, for example the Omani Society for the Welfare of the Disabled.53 Such giveaways are followed by intense media campaigns where photos of donation ceremonies as well as large sections of newspapers pages are published through which the public is informed of the tobacco industry’s contributions.53 Further, the tobacco industry has developed and funded youth smoking prevention programmes.54 A tobacco survey among Omani youth in 2010 revealed student exposure to pro-cigarette advertisements (64%), possessing an object with a cigarette brand logo (10%) and being offered free cigarettes from a representative (7.3%) as an indication of the covert activities of the tobacco industry in Oman.21

The way forward

Achieving a 30% reduction in tobacco use by 2025, relative to the base-year of 2010 (from 17.9% to 12.5%)4,7 would be possible through effective implementation of the highest level of the six MPOWER strategies combined. A recent WHO study showed that Oman could achieve a relative reduction of 36%, 46%, and 54% in the prevalence of tobacco use over 5, 15, and 40 years, respectively [Table 3].55 Thus, urgent action to implement various provisions of the Convention and MPOWER policies is required.

Table 3: Effects of implementing the highest polices of MPOWER measure on smoking prevalence and mortality in Oman.

|

Protect people from second-hand smoke |

-12.60% |

-15.80% |

32 318 |

16 032 |

127 |

16 159 |

10 503 |

|

Offer cessation services |

-3.50% |

-8.70% |

17 740 |

8 801 |

70 |

8 870 |

5 766 |

|

Run mass media campaigns |

-3.30% |

-3.90% |

7 980 |

3 959 |

31 |

3 990 |

2 594 |

|

Warning on cigarette packages |

-2.00% |

-4.00% |

8 185 |

4 060 |

32 |

4 092 |

2 660 |

|

Enforcement of marketing restrictions |

-5.00% |

-6.50% |

13 301 |

6 598 |

52 |

6 650 |

4 323 |

|

Raise cigarette taxes |

-15.40% |

-30.90% |

63 175 |

31 340 |

248 |

31 588 |

20 532 |

Source: see reference55; LMIC: low and middle-income countries.

First, given that the latest surveys were more than five years ago, these provide limited information on tobacco use and are largely limited to the Omani population. Although the third Global Youth Tobacco Survey was conducted in mid-2016 and plans are underway to conduct the Global Adult Tobacco Survey for the first time in Oman, a national tobacco surveillance system that involves conducting these surveys regularly (i.e., every five years) needs to be firmly established. Such a system would provide comprehensive information on tobacco use as well as on the impact of tobacco control policies. Monitoring tobacco use allows examination of the changing trends in tobacco use and studying emerging products such as Midwakh (an Arabic style pipe similar but smaller than western style pipe which uses shredded tobacco blended with flavors) and electronic nicotine delivery devices such as e-cigarettes and e-shisha importation and distribution (which was officially banned in 2015).56,57 More importantly, it provides vital information to understand the influence of prevention policies on this behavior to guide policy makers.

Second, a comprehensive national ban on tobacco use in enclosed public spaces should be implemented. This ban should eliminate the current allowance in sub-national laws permitting DSA within enclosed public spaces, which does not meet Oman’s Article 8 obligations or WHO recommendations.12 It should also eliminate the current waterpipe exemption for cafes. Only a total ban in indoor public places protects people’s health.

Third, given the success of brief advice by health care providers,58 helping patients quit should be part of routine primary care. The WHO Toolkit59 for delivering the 5A’s and 5R’s brief tobacco interventions in primary care could readily be adapted and integrated into the Omani health care system.

Fourth, Oman and other GCC countries should consider requiring stronger, larger PHW on all cigarette packs (> 50% of the principle display area) placed on the upper side of the pack to sustain their effectiveness.60 Consideration could be given for PHW on waterpipes instruments. Simultaneously, Oman and other GCC countries may initiate a review process to look into implanting plain packaging in line with the recommendations of Article 11.61

Fifth, the current social-cultural context appears conducive for an environment that is restrictive for tobacco marketing. Nevertheless, it is imperative that legislation be put in place to enact current media restrictions. In addition, such legislation should be expanded to control all promotional activities including point-of-sale advertisement as well as advertisement on individual packs. A mechanism is also needed to enforce these and other tobacco control measures.

Sixth, tobacco products in Oman are among the least expensive globally. Given the challenges in raising import duties, Oman should consider imposing other sufficient excise taxes such as domestic taxes and/or health tax on both domestic and imported brands in order to make tobacco products less affordable. Although political support exists for such a move, especially in light of the crash of the global oil market, the type, amount of taxes and their mechanism of administration should be defined based on successful regional and global experiences.

Finally, the GCC is a regional market and often functions as a unified legislative body for commerce and trade. Tobacco control efforts related to trade are therefore handled at this regional level rather than independently by each GCC state. Since all six countries have ratified the Convention and face similar challenges arising from WTO membership and bilateral free-trade agreements, they should work together to prioritize and establish a strong regulatory framework for the control of tobacco and other health risk factors.62

Conclusion

This review documents, for the first time, Oman’s experience of tobacco control in two very distinct eras; pre-1970 when smoking was severely punished and post-1970 when tobacco use became common. Although Oman remains a country with the lowest tobacco use among the GCC states and the Eastern Mediterranean region, its prevalence is projected to increase to 33.3% by 2025. Limited progress has been made in tobacco control since Oman’s accession to the Convention in 2005. Oman should adopt a comprehensive tobacco control legislation that encompasses the highest attainable policies recommended by MPOWER to not only curb tobacco use and maintain current low prevalence levels, but to attain a prevalence of < 5%. This would invariably contribute to the global goal of 25% mortality reduction from noncommunicable diseases by 2025.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the WHO. No funding was received for this study.

references

- 1. World Health Organization. Tobacco Fact sheet Nο. 339; May 2014 [cited 2015 June]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en/.

- 2. World Bank. Curbing the epidemic, governments and the economics of tobacco control. Washington D.C.: The World Bank 1999.

- 3. Eastern Mediterranean Regional of the World Health Organization. Key topics in tobacco control [cited 2015 June]. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/tobacco/publications/a-to-z.html.

- 4. World Health Organization. WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco smoking; 2015 [cited 2015 June]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/surveillance/reportontrendstobaccosmoking/en/index4.html.

- 5. Baheiraei A, Hamzehgardeshi Z, Mohammadi MR, Nedjat S, Mohammadi E. Personal and Family Factors Affecting Life time Cigarette Smoking Among Adolescents in Tehran (Iran): A Community Based Study. Oman Med J 2013 May;28(3):184-190.

- 6. World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control [cited 2016 May]. Available from: http://www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en/.

- 7. World Health Organization. Follow-up to the Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases [cited 2016 May]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA66/A66_R10-en.pdf.

- 8. Kutschera C. Oman: The Death of the Last Feudal Arab State [cited 2015 November]. Available from: http://www.chris-kutschera.com/A/Oman%201970.htm.

- 9. Kifner J. Oman gives super party: it’s come a long way [cited 2015 November]. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/1985/11/19/world/oman-gives-super-party-it-s-come-a-long-way.html.

- 10. Morton MQ. Buraimi: The Struggle for Power, Influence and Oil in Arabia. US: Tauris & Co Ltd; 2013.

- 11. Sergey Plekhanov. A Reformer on the Throne: Sultan Qaboos Bin Said Al Said: Trident Press Ltd; 2004.

- 12. World Health Organization. WHO Report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2015: Raising taxes on tobacco: Technical Notes I, II and III and Annex I to the Geneva 2015.

- 13. World Health Organization. MPOWER: A policy package to reverse the tobacco epidemic [cited 2016 May]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/mpower_english.pdf.

- 14. Sulaiman AJ, Al-Riyami A, Farid S. Oman Family Health Survey 1995: Principal report. Muscat: Ministry of Health, Oman 2000.

- 15. Al-Riyami A, Afifi M, Al-Kharusi H, Morsi M. National Health Survey: study of lifestyle risk factors. Muscat: Ministry of Health 2003.

- 16. Al-Riyami A, Abdelaty MA, Jaju S, Morsi M, Al-Kharusi H, Al-Shekaili W. World Health Survey 2008. Department of Research, Directorate General of Planning, Ministry of Health Oman. 2012.

- 17. Ministry of Health. Summary Report of the Nizwa Healthy Lifestyle Project Survey 2001. Muscat 2002. Ministry of Health Oman.

- 18. Al-Farsi M, El-Melighy M, Mohammed S, Ali L. Healthy lifestyle study: Assessment of lifestyle risk factors among Sur city population. Sur: Ministry of Health 2006.

- 19. Al-Siyabi H, Al-Anquodi Z, Al-Hinai H, Al-Hinai S. Nizwa Healthy Lifestyle Project Evaluation Report 2010. Directorate General of Health Services, Ad Dakhliyah Region, Ministry of Health, Oman 2010.

- 20. Al-Muzahmi SN, El-Aziz SA, Al-Lawati JA, Al-Thuhli YS, Foad DH. Global Youth Tobacco Survey 2007. Muscat: Ministry of Health 2007.

- 21. Al-Muzahmi SN, Abdou SA, Al-Lawati JA, Al-Thuhli YS, Al-Rawahi SN. Global Youth Tobacco Survey 2010. Muscat: Ministry of Health 2015.

- 22. Minister of Health. Ministerial decision 55/1993 banning smoking in all Ministry of Health buildings. Office of the Minister of Health 1993.

- 23. Cabenet of Ministers. Instructions for smoke-free buildings policy, meeting 9/94 held in November 1994 (referenced in the preamble of the administrative decision No. (19/95) of the Secretary General of Sutan Qaboos University: Office of the Secretary General of Sultan Qaboos University; January 1995.

- 24. Minister of Education. Ministerial decision 99/2001, Regulations for students in general education schools: Office of the Minister 2001.

- 25. Albawaba News. Oman Air to Ban Smoking [cited 2016 January]. Available from: http://www.albawaba.com/news/oman-air-ban-smoking.

- 26. Cheif Executive of Oman Airports Management Company. No smoking policy in Seeb International Airport: Cheif Executive Instructions CEI/25. Muscat 2005.

- 27. Muscat Daily. Under a cloud of smoke [cited 2015 November]. Available from: http://www.muscatdaily.com/Archive/Features/Under-a-cloud-of-smoke-35ep.

- 28. Al-Lawati JA, Al-Thuhli Y, Qureshi F. Measuring Secondhand Smoke in Muscat, Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2015 May;15(2):e288-e291.

- 29. Requirements to regulate smoking in enclosed public places, Muscat Municipality Decision 33/2010.

- 30. Kuwait News Agency. The Sultante of Oman bans waterpipes in hotels, restaurents and cafe shops [cited 2016 May]. Available from: http://www.kuna.net.kw/ArticlePrintPage.aspx?id=1149948&language=ar.

- 31. Health Ministers’ Council for GCC states. The eighth Gulf symposium for smoking control. December 1994.

- 32. Ministry of Commerce and Industry. Ministerial decree No 12/2012 for the approval of the technical regulations for labelling tobacco products. Muscat 2011.

- 33. Borland RM. Advertising, media and the tobacco epidemic. In: China tobacco control report [cited 2008 February]. Available from: http://tobaccofreecenter.org/files/pdfs/reports_articles/2007%20China%20MOH%20Tobacco%20Control%20Report.pdf.

- 34. Ministry of Commerce and Industry. Ministerial decree 239/2013 for the regulations of promotions. Official Gazzet issue No. 1041. Muscat 2013.

- 35. Ministry of Commerce and Industry. Ministerial decree 129/2015 for regulations of sale discounts. Official Gazzet issue No. 1100. Muscat 2015.

- 36. Khoja T, Hussien MS. Resolution on tobacco control issued by Health Ministers’ Council for Cooperation Council States 2012.

- 37. AlBalad online newspaper. Raising tariffs on tobacco in the Gulf next September [cited 2016 May]. Available from: http://albaladoman.com/38964.

- 38. World Health Organization. WHO technical manual on tobacco tax administration [cited 2016 May]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/tax_administration/en/.

- 39. Saidi NH. Taxes and tobacco consumption: GCC policy harmonization vital [cited 2015 December]. Available from: http://www.arabnews.com/news/824896.

- 40. Office of the United States Trade Respresentative Executive office of the President. Final text of the Free Trade Agreement between United States and Oman [cited 2015 December]. Available from: http://www.ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/oman-fta/final-text.

- 41. Al-Zidjali TM. Country report to the FAO international technical conference on plant genetic resource [cited 2016 Jan]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/agphome/documents/PGR/SoW1/east/OMAN.pdf.

- 42. Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries. The first proposal for services to be provided to farmers and suitable alternatives to reduce tobacco cultivation in the Sultanate. Presentation at the first meeting of the Committee for the reduction of tobacco cultivation in the Sultanate of Oman 2014.

- 43. National Centre for Statistics and Information. Export, Import data obtained through official communications available on request 2014.

- 44. Batmanghelidj E. How Iran smuggles Its smokes [cited 2016 Jan]. Available from: http://roadsandkingdoms.com/2014/how-iran-smuggles-its-smokes/.

- 45. Regional office for the Eastern Mediterranean, World Health Organization. Oman Tobacco Industry Profile. Fact sheets distributed to participants during the regional training of trainers on the implementation of the who FCTC Article 5.3 guidelines, Amman, Jordan, 8-10 December 2014.

- 46. Ministry of Commerce and Industry. Ministerial decree 139/2015 related to cigarettes and tobacco products. Official Gazzet issue No. 1100. Muscat 2001.

- 47. Minister of Commerce and Industry. Ministerial decision on ban of imports and sale of smokeless tobacco. In: Minister of Commerce and Industry, ed. Decision 38/2010. Muscat 2010.

- 48. Public Authority of Consumer Protection. Administrative decision to ban circulation of smokeless tobacco (in Arabic). Official Gazette. 2015(1089):48.

- 49. Joossens L, Merriman D, Ross H, Raw M. How eliminating the global illicit cigarette trade would increase tax revenue and save lives. Paris: International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2009.

- 50. World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Voice of truth (2nd edition) [Cited 2016 January]. Available from: http://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/dsa910.pdf?ua=1.

- 51. Oman Working Group. Minutes of meeting held at Muscat Intercontinental Hotel on Wednesday January 29, 1992 [cited 2016 January]. Available from: https://industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/#id=rxpy0198.

- 52. Letter of Minister of Commerce and Industry 549/2010 and Enhance (BAT) Compnay’s request to reduce size of pictorial health warnings and pospone thier implementation in Oman.

- 53. The Charitable Association for the Disabled Children receives grant of US$20,000. Alwatan Newspaper Issue 1434, 21 February 2001 and Times of Oman Issue 334, 22 January 2004.

- 54. Letter on Youth Smoking Prevention Programme by the Middle East Tobacco Association (META) to Undersecretery for Health Affairs and Deputy of Muscat Municipality dates October 1999.

- 55. Levy DT. The Abridged SimSmoke Oman (Powerpoint presentation). Regional meeting on achieving the NCD tobacco target (30% reduction by 2025), Tunis, Tunisia, 8-9 June, 2015.

- 56. Public Authority for Consumer Protection. Decision 698/2015 to Ban Distribution of E-Cigarettes and E-Shisha. Official Gazette. 2015(1127):55.

- 57. Ministry of Commerce and Industry. Ministerial Decree 327/2015 to Ban importation of E-cigarettes and E-Shisha. Official Gazette. 2015(1130):53.

- 58. West R, Raw M, McNeill A, Stead L, Aveyard P, Bitton J, et al. Health-care interventions to promote and assist tobacco cessation: a review of efficacy, effectiveness and affordability for use in national guideline development. Addiction 2015 Sep;110(9):1388-1403.

- 59. World Health Organization. Toolkit for delivering the 5A’s and 5R’s brief tobacco interventions in primary care [cited 2016 May]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/smoking_cessation/9789241506953/en/.

- 60. Borland R, Wilson N, Fong GT, Hammond D, Cummings KM, Yong HH, et al. Impact of graphic and text warnings on cigarette packs: findings from four countries over five years. Tob Control 2009 Oct;18(5):358-364.

- 61. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Guidelines for implementation of Article 11 [cited 2016 May]. Available from:http://www.who.int/fctc/guidelines/adopted/article_11/en/.

- 62. Al-Bahlani S, Mabry R. Preventing non-communicable disease in Oman, a legislative review. Health Promot Int 2014 Jun;29(Suppl 1):i83-i91.