Procedural sedation is recognized as a vital component adjunct to regional anesthesia, alleviating patients’ anxiety, discomfort, and pain.1 The increasing demand for procedural sedation among patients undergoing regional anesthesia has become a clinical necessity, prompting the exploration and development of novel sedative agents that combine efficacy and safety. Intravenous (IV) sedatives such as midazolam, ketamine, and dexmedetomidine have traditionally played a prominent role due to their sedative and anxiolytic properties and are routinely used in anesthesia and sedation. The downside of these agents is their potential to cause unwanted side effects, such as hemodynamic instability, respiratory depression, or delayed awakening resulting from prolonged sedation after the procedure.2,3 Propofol is a highly effective anesthetic for intraoperative and procedural sedation, known for its safety and rapid recovery times. It is associated with higher post-anesthesia recovery scores, better sedation, and improved patient cooperation.4 However, propofol can cause respiratory depression, hemodynamic instability, and pain on injection.5 Prolonged use may lead to hypertriglyceridemia and, rarely, but serious propofol infusion syndrome. Additionally, propofol lacks a specific reversal agent, and its metabolism depends on liver and kidney function, which may pose challenges in patients with organ dysfunction.6

Remimazolam has gained considerable attention for its remarkable pharmacological profile, characterized by rapid onset, ultra-short duration of action, and a favorable safety profile, making it a promising agent for procedural sedation.7 In contrast to propofol, remimazolam offers more stable hemodynamics with a lower risk of hypotension and respiratory depression, particularly in vulnerable patients. It also has an available reversal agent (flumazenil) and a lower risk of injection pain or hypertriglyceridemia due to the absence of lipid content.2,6 A recent study demonstrated that remimazolam is an effective sedative for cesarean section under spinal anesthesia, reducing the incidence and severity of intraoperative nausea and vomiting with minimal hemodynamic impact compared to midazolam, offering an additional clinical advantage.8 Since it is metabolized by tissue esterase and has a context-sensitive half-time of 6–7 minutes, repeated bolus doses every 5 minutes are recommended.9,10 A recent meta-analysis has shown that remimazolam has comparable efficacy and a greater safety profile than propofol for sedation during gastrointestinal endoscopies.11 Given that its clearance is unaffected by liver or kidney dysfunction, remimazolam can be safely used as a continuous infusion. To date, few studies have investigated the safe use of remimazolam for continuous administration.12

The current literature includes a limited number of studies examining continuous remimazolam infusion for sedation, particularly in patients with increased anesthetic risk. We aimed to determine whether recovery times differ between continuous infusions of remimazolam and propofol. The secondary objective was to determine the necessary range of continuous dose of remimazolam for procedural sedation, and to compare the performance in sedative and amnestic effects of continuous infusion of remimazolam and propofol, together with potential side effects for non-healthy (American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) II/III) patients.

Methods

A single-center, prospective, observational study conducted at Sestre Milosrdnice University Hospital Center, Croatia, from February to June 2023, following approval by the institution’s ethics committee (approval number 003-06/22-03-034) and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent before participation was obtained from 90 consecutive patients (ASA II and III) who required sedation for surgical procedures under spinal anesthesia. Exclusion criteria included age < 18 or > 80 years, allergy to any of the drugs used, body mass index < 18 or > 30 kg/m2, psychiatric diagnoses, and patient refusal.

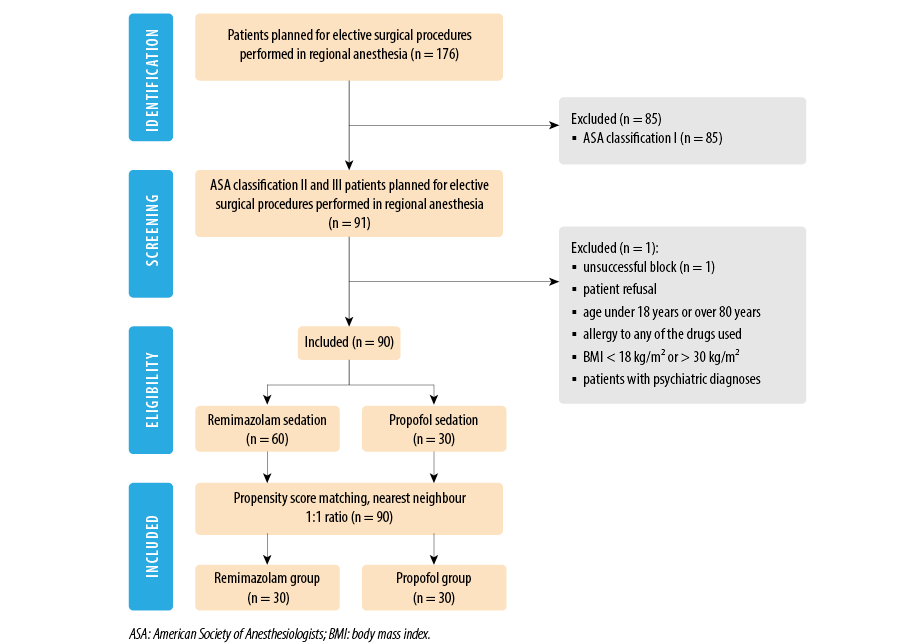

Demographic and clinical data were recorded on a standardized form (age, sex, height, and weight). Clinical data recorded before the start of the procedure were ASA status, bispectral index (BIS), Modified Observer’s Assessment of Awareness/Sedation Scale (MOAA/S), and Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS). This observational study included a total of 90 patients: 60 patients were sedated with remimazolam and 30 with propofol [Figure 1]. Patients received no premedication. Standard intraoperative monitoring was applied and included noninvasive blood pressure, continuous electrocardiogram, and pulse oximetry (SpO2). The level of sedation was assessed using the MOAA/S scale, with values 2–3 representing moderate sedation, considered adequate for the successful implementation of the procedure.13 Additionally, the RASS scale was used as another validated tool for monitoring sedation depth, with target values ranging from -1 to -3.14 BIS served as a primary indicator of the depth of consciousness. All patients underwent surgery under spinal anesthesia. The procedures included infraumbilical orthopedic, vascular, and inguinal hernia repair surgeries. Spinal anesthesia was performed according to a standardized procedure, and after satisfactory sensory and motor changes were established, additional anesthesia monitoring (BIS) was set up and MOAA/S and RASS scores were assessed. BIS, MOAA/S, RASS scale, infusion speed and duration, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, and SpO2 were recorded every five minutes. Remimazolam and propofol induction doses, onset time of sedation, and time to recovery were noted. The total doses of remimazolam and propofol, as well as the total sedation time,

were recorded.

Figure 1: The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flowchart outlines the selection process for the study.

Figure 1: The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flowchart outlines the selection process for the study.

The recommended dosage of remimazolam for the induction of sedation is 5 mg IV.15 We began with the same initial dose of 5 mg IV bolus and measured the time to achieve BIS < 80; if this level was not reached, initial dosage of 2.5 mg IV was given. After induction, continuous infusion was started from a syringe pump with 20 mg of remimazolam (Byfavo™ 20 mg powder for solution for injection) supplemented with 0.9% saline to 20 mL, to achieve 1 mg/mL dilution, with dose titration depending on BIS values. The initial propofol dose for reaching BIS values < 80 was 0.5 mg/kg IV (Propofol 10 mg/mL MCT Fresenius™), with further continuous dose titration depending on BIS values. The target BIS values were 60–80, which indicates moderate sedation, and infusions of the drugs were adjusted accordingly to avoid patients being either inadequately or excessively sedated. Onset time of sedation, defined as the time to reach value of BIS < 80 for both drugs, were recorded. At the end of the procedure, after stopping the administration of the drug, the time to recovery (time required from the end of the infusion to the value of BIS > 80; awake state) was measured. The total amount of remimazolam and propofol administered was recorded at the end of the procedure. Side effects including hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg), bradycardia (heart rate < 50 beast/minute), low blood oxygen saturation (SpO2 < 90%), apnea (absence of breathing effort ≥10 seconds), memory of events (evaluated using the Brice questionnaire), and body movements during the operation, as well as the drugs used to treat side effects, were noted.

The required sample size was estimated based on the median recovery time, reported as 2.3 minutes (IQR = 1.8–3.3) for remimazolam and 5.0 minutes (IQR = 3.5–7.8) for propofol.16 Based on these medians and considering a significance level of 0.05 and a power of 80%, an estimated minimum necessary sample size of 10 participants per group we calculated. Normality of the distribution of variables was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Continuous variables are shown as mean ± SD or median (IQR), as appropriate. To adjust for the confounding factors, a propensity score matching with optimal match without replacement and 1:1 nearest neighbor method with logistic regression distance was used. The matching demographic and clinical variables included age, sex, body mass index, ASA status, history of hypertension and diabetes, and initial BIS, MOASS, and RASS scores. The quality of the matching was assessed using the standardized mean difference where an absolute standardized mean difference of up to 0.1 was considered an excellent balance. In analysis after propensity matching, continuous variables are compared using t-test or Mann Whitney U test. Categorical variables were represented as number and corresponding percentage and differences tested with the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for frequencies < 5. For statistical analysis, Python (Centrum voor Wiskunde en Informatica, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) Statsmodels (v. 0.14.0), and ScyPy (v. 1.11.2) were used. Graphical representations were made using Python’s Matplotlib (v.3.5.2).17 The data associated with the paper are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Results

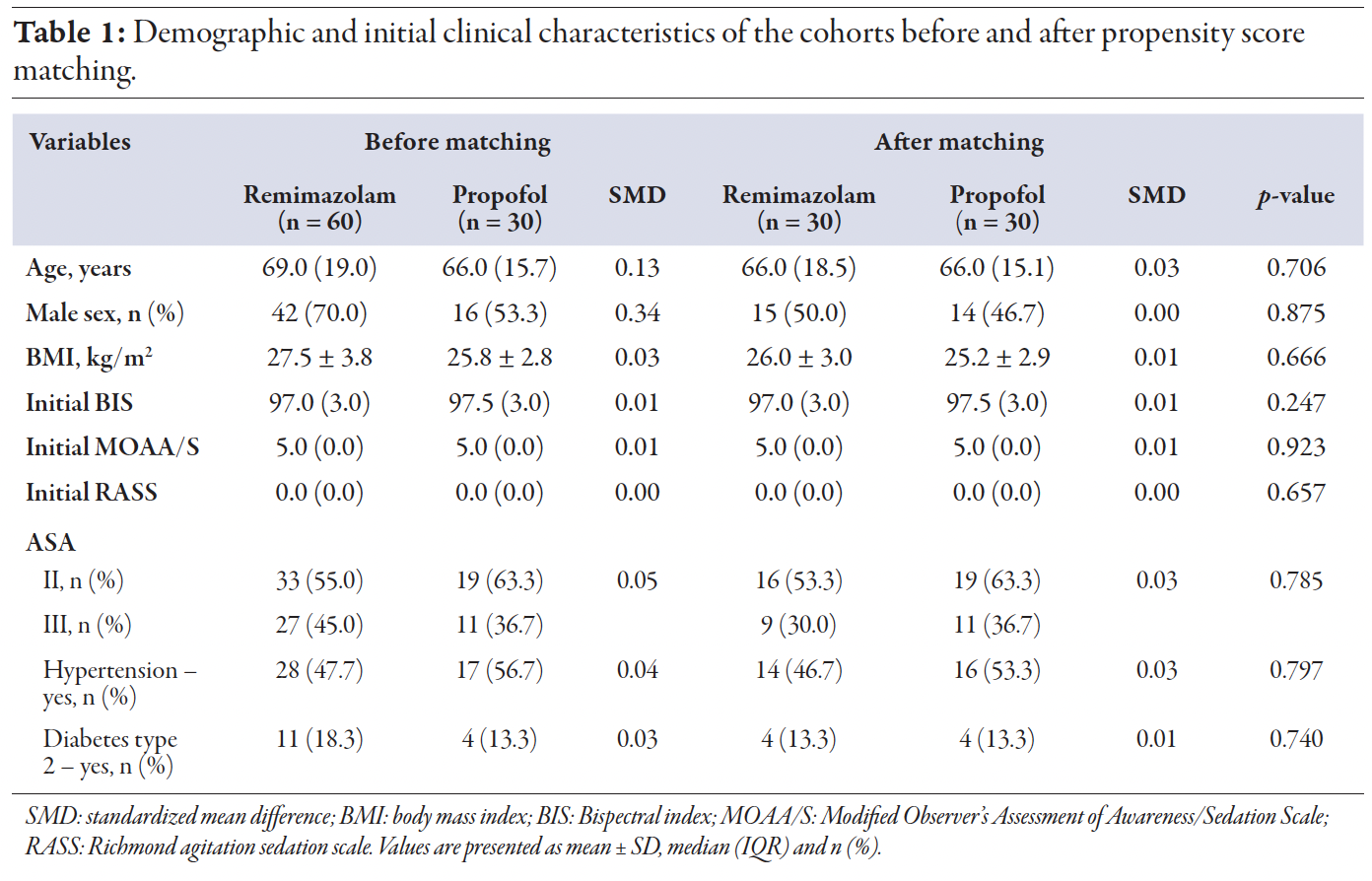

A total of 90 patients underwent spinal anesthesia with intraoperative sedation. Sixty patients were sedated with remimazolam and 30 with propofol. Before matching, two of the nine features were unbalanced, however, after matching, all features were balanced. Following propensity score matching, there was no significant difference in the patients’ demographic and initial clinical characteristics [Table 1].

Table 1

Table 1

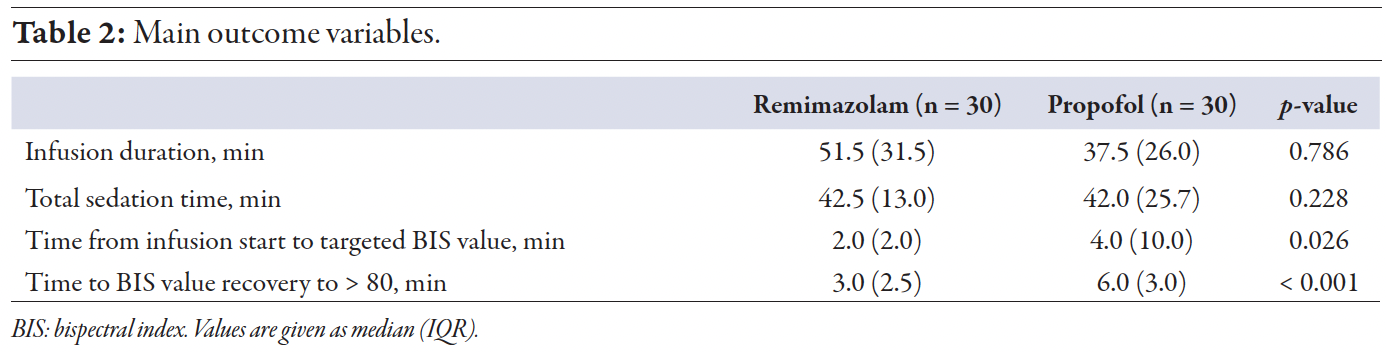

In the matched cohort, the median time to the targeted BIS value was statistically significant, with 2.0 (2.0) min for remimazolam and 4.0 (10.0) min for propofol, p = 0.026. Achieving BIS recovery > 80 was faster for remimazolam, at 3.0 minutes (IQR = 2.5), compared to 6.0 min for propofol (IQR = 3.0), p < 0.001. There was no significant difference in infusion duration times or total sedation times [Table 2].

Table 2

Table 2

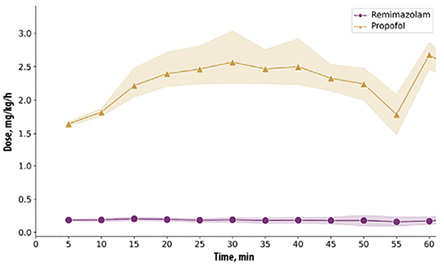

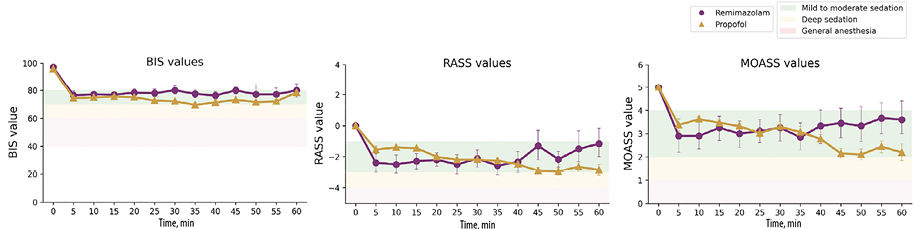

The median continuous infusion dose of remimazolam was 0.2 (0.1) mg/kg/h, while it was 1.9 (0.1) mg/kg/h for propofol [Figure 2]. The doses applied resulted in moderate sedation range starting from the 5th minute after induction. Across all recorded time points, BIS values (70–80) were observed in 46.5% of cases, RASS scale (-3 – -1) in 50.8%, and MOAA/S scale (2–3) in 28.8% [Figure 3].

Figure 2: Continuous remimazolam and propofol doses applied.

Figure 2: Continuous remimazolam and propofol doses applied.

Figure 3: A comparison of achieved bispectral index (BIS), Richmond sedation scale (RASS), and Modified Observer’s Assessment of Awareness/Sedation Scale (MOAA/S) between remimazolam and propofol groups.

Figure 3: A comparison of achieved bispectral index (BIS), Richmond sedation scale (RASS), and Modified Observer’s Assessment of Awareness/Sedation Scale (MOAA/S) between remimazolam and propofol groups.

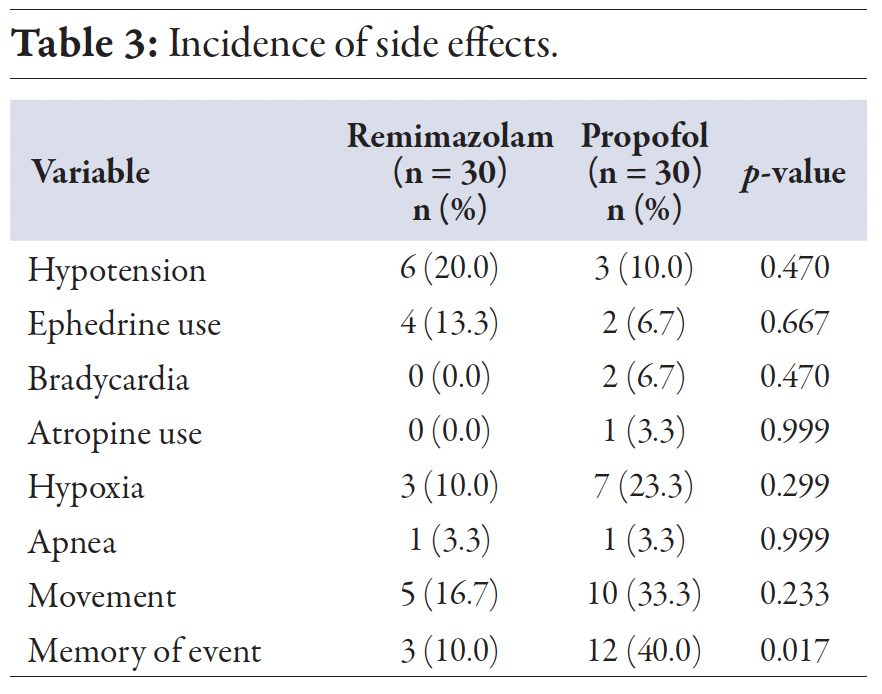

Regarding side effects, hypoxia was the predominant issue during propofol sedation, observed in seven (23.3%) cases, compared to three (10.0%) in the remimazolam group, but the difference was not statistically significant. Hypotension was the most prevalent side effect in the remimazolam group, occurring in six (20.0%) cases, compared to three (10.0%) in the propofol group, which was not statistically significant. There was no difference in the correction of hypotension with ephedrine between the two groups. Bradycardia was the least frequent side effect, observed only in two cases in the propofol group, with atropine used in only one case. No cases of bradycardia occurred in the remimazolam group [Table 3]. The only statistically significant difference between the two groups was in memory of the event, with 12 (40.0%) patients in the propofol group and three (10.0%) patients in the remimazolam group reporting retention of the experience during the procedure (p = 0.017).

Table 3

Table 3

Discussion

We found a statistically significantly faster recovery time after discontinuation of continuous remimazolam infusion compared to propofol. The recovery time to achieve a BIS value > 80 following remimazolam infusion was 3.0 min compared to 6.0 min for propofol. Additionally, a continuous remimazolam infusion at a median dose of 0.2 mg/kg/h provided effective, satisfactory, and safe sedative and hypnotic effects in non-healthy patients.

In recent years, numerous studies have explored remimazolam’s potential for intraoperative sedation. However, few have investigated its continuous administration for sedation, especially in non-healthy individuals, and those that did often report inconsistent dosing regimens.

A key finding of this study is the recovery time of BIS values following continuous infusion, where median time after cessation of remimazolam infusion to achieve BIS values a > 80 was 3.0 min while for propofol group was 6.0 min (p < 0.001). Previous studies have shown that remimazolam and propofol have similar context-sensitive half-time, indicating only subtle differences in recovery time.18 However, in a study using remimazolam for continuous sedation during impacted third molar extractions, the time to spontaneous eye opening was 8.0 min, similar to our findings, despite a higher infusion rate of 0.40 mg/kg/h.19 A recent meta-analysis highlighted the fact that the reported time to recovery varies greatly.20 This meta-analysis, which included only studies on procedural sedation for short endoscopic procedures, also pointed out great discrepancy in results, attributed to the inclusion of various patient populations, different procedural durations and complexities, and a lack of reporting on relevant comparative safety or efficacy outcomes. Remimazolam does not exhibit cumulative sedative effects with increased duration of dosing up to nine hours under general anesthesia. However, changes in the infusion rate near the end of the procedure, difference in the BIS score at the end of infusion, and female sex can result in up to five minute differences in time to extubation.21 Although a three-minute difference in recovery time may appear small, it can be important in everyday clinical practice, especially in busy hospitals. In high-volume surgical settings, even small time savings can add up, helping operating rooms run more efficiently, reducing time in the post-anesthesia care unit, and keeping schedules on track. Faster recovery also allows patients to spend less time under sedation, which can lower the risk of complications such as airway problems or delayed return of protective reflexes, especially in older or high-risk patients. For outpatient procedures, quicker recovery can lead to earlier discharge and better patient flow. Overall, shorter recovery times help improve workflow, reduce the need for extended monitoring, lower sedation-related risks, and allow patients to return to normal activities faster, all of which contribute to better healthcare efficiency and patient satisfaction.

Few studies have investigated the management of sedation using continuous remimazolam infusion in non-intubated patients. By achieving BIS values within the target range of 70–80, we found that the median continuous dose of remimazolam of 0.19 (0.1) mg/kg/h provided precision in tailoring sedation to the desired needs. The aim of supplementing BIS with MOAA/S and RASS score as parameters of depth of sedation was to address the limitations of BIS alone, enable more precise drug titration, improve intraoperative sedation assessment, and enhance complications prediction. A study that targeted RASS score of -2–0 to titrate remimazolam dosing for continuous sedation to relief agitated delirium in non-intubated older patients after orthopedic surgery found that the maintenance dose required to achieve it was 0.1–0.3 mg/kg/h, similar to our study.22 In elderly patients undergoing hip replacement under combined spinal-epidural anesthesia, to maintain BIS values < 80 and MOAA/S score around 3, the ED50 and ED95 for continuous remimazolam infusion were found to be 0.212 mg/kg/h and 0.288 mg/kg/h respectively, also consistent with our findings.23

A continuous propofol infusion of 1.9 (1.0) mg/kg/h was used to maintain BIS level between 70 and 80. Many studies have shown that 2.5–3 mg/kg/h of continuous propofol infusion is sufficient to achieve the target BIS values of 60–80 for sedation.18,19 The patients in our study were not healthy (ASA II and III) with a mean age > 65 years. Studies indicate that advanced age and higher ASA classification reduce propofol requirements, which is consistent with our findings.24–26

The only statistically significant difference in adverse effects observed was related to memory of the procedure. Only 10.0% of patients in the remimazolam group reported experiencing memory of the procedure, compared to 40.0% in the propofol group (p = 0.017). In previous studies, using larger dosing regimen, 96.6% of patients reported no or minimal memory of the procedure.13 Other findings regarding memory recovery are mostly from studies following general anesthesia, with remimazolam groups having poorer memory recovery.27 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis comparing remimazolam and propofol for procedural sedation found statistically significant reduction in the incidence of hypotension with remimazolam.28 In contrast, our results showed no statistically significant difference in hypotension between the groups, though hypotension occur more frequent in the remimazolam group (20.0% vs. 10.0%, respectively). This may be attributed to the use of spinal anesthesia and the lower propofol dose in our study. Hypoxia is another side effect that occurs more frequently with propofol than remimazolam.29 In our study, we documented hypoxia in 10.0% of cases in the remimazolam group and 23.3% in the propofol group. Although this difference is not statistically significant, it correlates with previous findings.30,31 The incidence of apnea was very low, occurring in only one case in both groups and resolved without the need for intervention. However, a recent study reported a notable incidence of apnea during moderate to deep remimazolam sedation, using 0.1 mg/kg in two minutes followed by 0.5 mg/kg/h of remimazolam. While the doses were higher than those used in our study, they highlight the need for close monitoring despite the absence of severe adverse events.32 Although no significant side effects were recorded in this study, nor did they lead to discontinuation of medication or surgery, an important possibility is the use of flumazenil as an antagonist to remimazolam. A notable limitation associated with propofol is its absence of a specific antagonist, thereby conferring an advantage to remimazolam.

This study is limited by its relatively small sample size, which may affect result interpretation, and by the clinical relevance of a three-minute difference in recovery time between the drugs. As a single-center study involving sedation only in patients undergoing spinal anesthesia, the generalizability of these findings to other clinical settings or patient populations is limited. However, these findings support further investigation of remimazolam as a valuable sedative, especially for procedures requiring precise sedation control. Current studies show significant variability in dosing regimens, patient demographics, severity, and endpoints, highlighting the need for further research to establish more informative protocols or best practice standards.

Conclusion

Continuous infusion of remimazolam exhibits non-inferior efficacy and safety in providing sedative and hypnotic effects for intraoperative sedation in non-healthy patients undergoing spinal anesthesia, compared to propofol. Remimazolam has shown faster onset, significantly better recovery time and amnestic profile.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this study.

references

- 1. Höhener D, Blumenthal S, Borgeat A. Sedation and regional anaesthesia in the adult patient. Br J Anaesth 2008 Jan;100(1):8-16.

- 2. Kim SH, Fechner J. Remimazolam - current knowledge on a new intravenous benzodiazepine anesthetic agent. Korean J Anesthesiol 2022 Aug;75(4):307-315.

- 3. Monaco F, Barucco G, Lerose CC, DE Luca M, Licheri M, Mucchetti M, et al. Dexmedetomidine versus remifentanil for sedation under monitored anesthetic care in complex endovascular aortic aneurysm repair: a single center experience with mid-term follow-up. Minerva Anestesiol 2023 Apr;89(4):256-264.

- 4. Wang D, Chen C, Chen J, Xu Y, Wang L, Zhu Z, et al. The use of propofol as a sedative agent in gastrointestinal endoscopy: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013;8(1):e53311.

- 5. Koo BW, Na HS, Park SH, Bang S, Shin HJ. Comparison of the safety and efficacy of remimazolam and propofol for sedation in adults undergoing colonoscopy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicina (Kaunas) 2025 Apr;61(4):646.

- 6. Sahinovic MM, Struys MM, Absalom AR. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of propofol. Clin Pharmacokinet 2018 Dec;57(12):1539-1558.

- 7. Masui K, Stöhr T, Pesic M, Tonai T. A population pharmacokinetic model of remimazolam for general anesthesia and consideration of remimazolam dose in clinical practice. J Anesth 2022 Aug;36(4):493-505.

- 8. Lee K, Choi SH, Kim S, Kim HD, Oh H, Kim SH. Comparison of remimazolam and midazolam for preventing intraoperative nausea and vomiting during cesarean section under spinal anesthesia: a randomized controlled trial. Korean J Anesthesiol 2024 Dec;77(6):587-595.

- 9. Xin Y, Chu T, Wang J, Xu A. Sedative effect of remimazolam combined with alfentanil in colonoscopic polypectomy: a prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial. BMC Anesthesiol 2022 Aug;22(1):262.

- 10. Morimoto Y. Efficacy and safety profile of remimazolam for sedation in adults undergoing short surgical procedures. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2022 Feb;18:95-100.

- 11. Barbosa EC, Espírito Santo PA, Baraldo S, Meine GC. Remimazolam versus propofol for sedation in gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 2024 Jun;132(6):1219-1229.

- 12. Sheng XY, Liang Y, Yang XY, Li LE, Ye X, Zhao X, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of single ascending dose and continuous infusion of remimazolam besylate in healthy Chinese volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2020 Mar;76(3):383-391.

- 13. Kowalski R, Mahon P, Boylan G, McNamara B, Shorten G. Validity of the modified observer’s assessment of alertness/sedation scale (MOAA/S) during low dose propofol sedation: 3AP6-3. Eur J Anaesthesiol EJA 2007 Jun;24:26-27.

- 14. Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A, Thomason JW, Wheeler AP, Gordon S, et al. Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: reliability and validity of the richmond agitation-sedation scale (RASS). JAMA 2003 Jun;289(22):2983-2991.

- 15. Lee A, Shirley M. Remimazolam: a review in procedural sedation. Drugs 2021 Jul;81(10):1193-1201.

- 16. Lee HJ, Lee HB, Kim YJ, Cho HY, Kim WH, Seo JH. Comparison of the recovery profile of remimazolam with flumazenil and propofol anesthesia for open thyroidectomy. BMC Anesthesiol 2023 May;23(1):147.

- 17. Oliphant TE. Python for scientific computing. Comput Sci Eng 2007 May;9(3):10-20.

- 18. Masui K. Remimazolam besilate, a benzodiazepine, has been approved for general anesthesia!! J Anesth 2020 Aug;34(4):479-482.

- 19. Oue K, Oda A, Shimizu Y, Takahashi T, Kamio H, Sasaki U, et al. Efficacy and safety of remimazolam besilate for sedation in outpatients undergoing impacted third molar extraction: a prospective exploratory study. BMC Oral Health 2023 Oct;23(1):774.

- 20. Chang Y, Huang YT, Chi KY, Huang YT. Remimazolam versus propofol for procedural sedation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PeerJ 2023 Jun;11:e15495.

- 21. Lohmer LL, Schippers F, Petersen KU, Stoehr T, Schmith VD. Time-to-event modeling for remimazolam for the indication of induction and maintenance of general anesthesia. J Clin Pharmacol 2020 Apr;60(4):505-514.

- 22. Deng Y, Qin Z, Wu Q, Liu L, Yang X, Ju X, et al. Efficacy and safety of remimazolam besylate versus dexmedetomidine for sedation in non-intubated older patients with agitated delirium after orthopedic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Drug Des Devel Ther 2022 Aug;16:2439-2451.

- 23. Song Y, Zou XJ. Remimazolam dosing for intraoperative sedation in elderly patients undergoing hip replacement with combined spinal-epidural anesthesia. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2023 Aug;27(16):7485-7491.

- 24. Wells ME, Barnes RM, Caporossi J, Weant KA. The influence of age on propofol dosing requirements during procedural sedation in the emergency department. Adv Emerg Nurs J 2021 Oct-Dec;43(4):255-264.

- 25. Heuss LT, Schnieper P, Drewe J, Pflimlin E, Beglinger C. Safety of propofol for conscious sedation during endoscopic procedures in high-risk patients-a prospective, controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol 2003 Aug;98(8):1751-1757.

- 26. Nayar DS, Guthrie WG, Goodman A, Lee Y, Feuerman M, Scheinberg L, et al. Comparison of propofol deep sedation versus moderate sedation during endosonography. Dig Dis Sci 2010 Sep;55(9):2537-2544.

- 27. Nobukuni K, Shirozu K, Maeda A, Funakoshi K, Higashi M, Yamaura K. Recovery of memory retention after anesthesia with remimazolam: an exploratory, randomized, open, propofol-controlled, single-center clinical trial. JA Clin Rep 2023 Jul;9(1):41.

- 28. Zhang J, Cairen Z, Shi L, Pang S, Shao Y, Wang Y, et al. Remimazolam versus propofol for procedural sedation and anesthesia: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Minerva Anestesiol 2022 Dec;88(12):1035-1042.

- 29. Dong SA, Guo Y, Liu SS, Wu LL, Wu LN, Song K, et al. A randomized, controlled clinical trial comparing remimazolam to propofol when combined with alfentanil for sedation during ERCP procedures. J Clin Anesth 2023 Jun;86:111077.

- 30. Oka S, Satomi H, Sekino R, Taguchi K, Kajiwara M, Oi Y, et al. Sedation outcomes for remimazolam, a new benzodiazepine. J Oral Sci 2021 Jun;63(3):209-211.

- 31. Sharma AN, Shankaranarayana P. Postoperative nausea and vomiting: palonosetron with dexamethasone vs. ondansetron with dexamethasone in laparoscopic hysterectomies. Oman Med J 2015 Jul;30(4):252-256.

- 32. Oh C, Lee J, Lee J, Jo Y, Kwon S, Bang M, et al. Apnea during moderate to deep sedation using continuous infusion of remimazolam compared to propofol and dexmedetomidine: a retrospective observational study. PLoS One 2024 Apr 17;19(4):e0301635.