| |

A Retrospective Study of Ureteroscopy Performed at the Sultan Qaboos Hospital, Salalah from August 2001 –August 2006

Logesan Dhinakar, M.S., MCh(URO), MRCSEd

ABSTRACT

In the modern era of management of disorders of the upper urinary tract, ureteroscopy forms an important part in the armamentarium for the diagnosis and treatment of a variety of disorders that occur in the upper urinary tracts. The modern ureteroscopes have better vision and are less traumatic, making ureteroscopy a relatively safe procedure. Major complications are rare. An audit of a total of 128 ureteroscopies done in the Department of Urology over a six year period from August 2001 till August 2006 at the Sultan Qaboos Hospital, Salalah, was undertaken. The results are discussed in detail and compared with results from other centers. The management of a rare but dreaded major complication is discussed in detail.

Keywords: Ureteroscopy, Endopyelotomy, Electrohydraulic & Electrokinetic Lithotriptor, Balloon Dilator.

Submitted: 10 October 2006

Reviewed: 17 August 2007

Accepted: 21 September 2007

From the Department of Urology, Sultan Qaboos Hospital, Salalah, Sultanate of Oman.

Address Correspondence and reprint request to: Dr. Logesan Dhinakar, Department of Urology, Sultan Qaboos Hospital, Salalah, Sultanate of Oman.

E mail: logesandhinakar@hotmail.com

AIM

To do a detailed audit of ureteroscopy performed in the department of Urology at the Sultan Qaboos Hospital, Salalah, with the sole purpose of assessing our performance and comparing our results with other centers, in order to provide quality care for our patients.

INTRODUCTION

In the modern era of management of disorders of the upper urinary tract, ureteroscopy forms an important part of the armamentarium in the diagnosis and treatment of a variety of disorders that occur in the upper tracts. In the last two decades Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL), Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy (PCNL) and Ureteroscopy have replaced open surgery in a vast majority of cases of renal and ureteric calculus disease.1 Historically, the surgical treatment of ureteric calculi included cystoscopic procedures like ureteric catheterisation, ureteric dilatation, dormia wire basket stone extraction, ureteric meatotomy or open ureterolithotomy. In the last two decades ureteroscopy has become an outstanding breakthrough in the diagnosis and treatment of a variety of ureteral and renal conditions. Strictures of the ureters are managed ureteroscopically with either incision or balloon dilatation. Endoscopic management of ureteric tumors include biopsy, snaring and laser ablation all which can be performed through the ureteroscope. The use of the ureteroscope is extended to the kidneys. Cases such as Congenital PelviUreteric Junction (PUJ) obstruction can be managed by endopyelotomy (Ureteroscopic incision of PUJ) or balloon dilatation of PUJ. Renal pelvic or calyceal calculus can be effectively fragmented by flexible holmium laser or electrohydraulic probes passed through a flexible ureterorenoscope with subsequent passage of the stone fragments around a double ‘J’ stent (a self retaining tube placed by a cystoscope, between the pelvicalyceal system and the urinary bladder that enables free drainage of urine from the kidney to the bladder and aids the passage of stone fragments down the ureter around the stent without obstructing the flow of urine). The entire upper Urinary tract can be now visualized using the modern flexible ureterorenoscope. These ureteroscopes have a deflecting tip which enables clear visualization of the entire pelvicalyceal system. Low grade transitional cell carcinoma of the pelvicalyceal system can be ablated by laser probe passed through the flexible ureterorenoscope.Follow up ureteroscopy is done and tumor ablation can be repeated if recurrence occurs.

METHOD

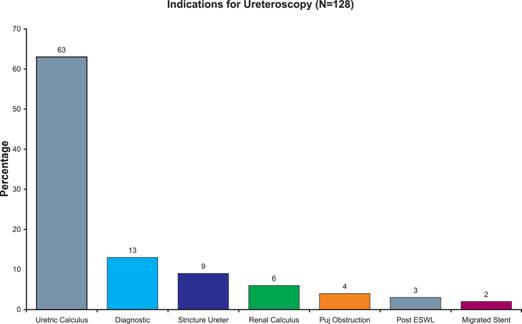

A retrospective audit of a total of 128 ureteroscopies done in the Department of Urology over a six year period from August 2001 till August 2006 at the Sultan Qaboos Hospital, Salalah, was undertaken. The following parameters were included namely, male to female ratio, indications, symptomatology, lab and radiological investigations, details like site, location and size of the calculus in the upper urinary tracts, types ofureteroscope used, the energy source used to fragment the calculi, results of the procedures performed, complications, frequency of post ureteroscopic stent placement and finally the hospital stay. The total number of males undergoing the procedure was 75 (58.6%) and females was 53 (41.4%). The age group in both males and females ranged from 20-70 years and the commonest age group undergoing the procedure in both sexes were between 30-40 years of age (52.8%). The indications for ureteroscopy have been for a variety of conditions and the most common one being that for calculus in the ureter - 81 patients (63.2%). The other indications were, diagnostic ureteroscopy - 17patients (13.3%), stricture of the ureter - 11 patients (8.6%), PUJ obstruction – 5 cases (3.9%) , Post ESWL Stein Strasse (stone street), (a condition which occurs when the fragments of the disintegrated calculus in the kidney or upper ureter descends down the ureter and lies one on top of the other appearing like a street packed with stones) – 4 patients (3.1%) , recovery of migrated stents 2 patients (1.56%) & renal calculus - 8 patients (6.25%).

Figure 1: Chart Showing the Indications of Ureteroscopy at Our Centre

There was an overlap of 6.9% between the indications for calculus and the indications for stricture as 63% cases of stricture of the ureter had associated calculi and was managed together. Three patients had repeat ureteroscopy for removal of residual fragments. Diagnostic ureteroscopy was done for patients who were admitted for recurrent attacks of loin pain or in patients presenting with repeated microscopic haematuria on urinalysis with no obvious cause evident on investigations. Most cases were negative for pathology on ureteroscopy. In a few patients flexible ureterorenoscopy showed calcific specks in the renal papillae.

The most predominant symptom in patients was loin pain, which was seen in over 88% of cases. Macroscopic haematuria was seen in 24% of the patients and nausea andvomiting in 38.4% of cases. Frequency of micturition was observed in 16.8% and fever in 10.4% of patients. The laboratory studies done were urine routine, urine culture & sensitivity, complete blood count, renal function tests, sr. calcium, phosphorus & uric acid. Urine routine was normal in 32.8% of cases, and showed microscopic haematuria in 50.4% of cases. Oxalate crystals were seen in urinalysis in 13.3% of cases. Urine culture grew organisms in 16.8% of patients. The commonest organism grown was E.Coli (94%). None of the patients showed increase in sr.calcium levels. About 6-8% of patients had a mild to moderate increase in sr.uric acid. They were advised to take plenty of oral fluids and a low purine diet with a regular follow up and treatment for the raised uric acid levels was instituted if conservative management failed.

The radiological studies done were plain X-ray KUB (kidney, ureter, bladder), Ultrasound examination (USG), Intravenous pyelogram (IVP) and in selected cases a non contrast spiral CT scan. Of the 89 patients with Calculus disease of both the ureter and kidney, the stone was visualized on plain x-ray KUB in 72 patients (80%). Ultrasound demonstrated ureteric calculi in 36.6% of the patients and most of them were either upper or lower ureteric calculi. Mid ureteric calculus was rarely visualized on USG unless there was an adequate ureteric dilatation above the calculus to enable the stone to be traced. USG also showed an associated dilatation of the pelvicalyceal system in 93 patients (72.6%). IVP was omitted in 34 patients (26.5%) either due to the presence of renal failure in these patients or was deemed unnecessary in cases of lower ureteric calculus where the stone location and size were adequately assessed by plain x-ray and USG forplanning ureteroscopy. In the cases where IVP was done, it was reported as normal in 12 patients (9.3%). There was mild to moderate dilatation of pelvicalyceal system and ureter in 58 patients (45.3%) and evidence of gross dilatation in 11 patients (8.6%).

Lesions like stricture of ureter were diagnosed in 11 patients (8.5%). In only 4 patients (3.1%), IVU showed non visualization (non functioning kidney) of the pelvicalyceal system. Non contrast spiral CT was used to locate ureteric calculi in 18 patients (14%) as the stone was not visualized on plain x-ray, USG and IVP, or the patient had renal failure and contrast study could not be done. Of the 89 patients for whom ureteroscopy was done for calculus disease of ureter and kidney, 35 (39%) presented on the right side and 46 (51.6%) on the left. Stones were bilateral in 8 patients (8.9%). The locations of the calculi were as follows: - 62 in lower ureter (70%), 12 in upper ureter (13.5%), 6 in mid ureter (6.5%), and 9 in the kidney (10%). In 6 patients (6.6%) calculus observed preoperatively was not seen during ureteroscopy. The average size of the calculus ranged from 5mm to over 1cm. The most common size of the calculi was between 5-7mm (66.6%). Calculus ranging from 7-9mm was seen in 13 patients (14.4%) and ones over 1cm were 11 in number (12.2%). Calculi less than 5mm were seen in only 6 patients (6.6%). The types of ureteroscopes used were 8.6 french olympus semirigid ureteroscope in 90 Patients (72%), 6.4 fr semirigid ureteroscope in 16 patients (12.8%) and 8.4 fr flexible ureterorenoscope in 19 patients (15.2%). Ureteric access was done in majority of cases using the balloon dilator to widen the ureteric orifice, and facilitate entry of the 8.6 fr ureteroscope. In 13 patients where a smaller ureteroscope was used namely the 6.4 fr, and in 12 patients where the 8.4 fr flexible ureteroscope was used ureteric orifice dilatation was not required as the orifice could be negotiated by the smaller sized tip of the ureteroscope. But in 3 patients for whom a 6.4 fr semirigid ureteroscopy was done and in 7 patients undergoing flexible ureteroscopy, ureteric orifice dilatation was still required to gain access to the ureter. This was due to technical reasons like narrow ureteric orifice or an abnormally located orifice (eg: - laterally placed orifice). The flexible ureteroscope is passed over a 0.038 inch wire guide placed up the ureter by a preliminary cystoscopy. In 2 patients (1.5%) a nottingham dilator (plastic semirigid ureteric orifice dilator) was used to dilate the ureteric orifice as we did not have the ureteric balloon dilator at that time. In 11 patients (8.59%) a preliminary Percutaneous Nephrostomy (PCN) was done as they presented with gross renal failure due to obstruction by stones or stricture of the ureter. In these patients renal failure was precipitated due to acute bilateral ureteric obstruction or acute obstruction to a normally functioning kidney where the other kidney was congenitally absent or diseased or has been removed for various reasons. The energy source used to fragment calculi during ureteroscopy was Electrokinetic Lithotriptor (EKL) in 53 patients (58.8%) and Electrohydraulic Lithotriptor (EHL) in 10 patients (11.1%). Stone basketting under vision was done using the dormia wire basket via the ureteroscope in 19 patients (21.1%) without the need for lithotripsy. The hospital stays of patients ranged from less than 2 days to more than 10 days. Majority of patients (61 cases) had a total hospital stay of 2-5 days (47.6%), 3 patients (2.3%) stayed for less than 2days, 37 patients (28.9%) stayed for 7-10 days and 27 patients (21%) stayed for more than 10 days.

RESULTS

On analyzing the overall results of ureteroscopy done the following data was obtained. In cases where ureteroscopy was done for calculus disease of the ureter (81 cases) a total of 58 patients (71.6%) had complete removal of the calculus. Over 70% of these patients had the calculus in the distal third of the ureter. The success rates for stone clearance of lower ureteric stones was over 80%. The success rate of stone clearance dropped to around 60% when ureteroscopy was done for proximal ureteric stones. Partial removal was possible in 6 patients (7.4%) and stones could not be removed in 6 patients (7.4%) either because the procedure was abandoned in 4 cases (4.9%) due to poor vision caused by bleeding and failure of fragmentation of the stones by lithotripsy in 2 cases (2.5%) due to the hardness of the stone. All 6 of them underwent open ureterolithotomy immediatly. Calculus seen preoperatively but not seen during ureteroscopy, was encountered in 6 cases (7.4%) due to spontaneous passage of the calculus prior to the procedure. Stone migration to the kidney during ureteroscopy occurred in 5 patients (6%). Stent placement after the procedure was based on presence of oedema at the site of the stone, presence of mucosal abrasions and in cases where the procedure was abandoned due to poor vision or stone migration to the kidney. Post ureteroscopic stenting of the ureter was done in 54 cases (42%).

Flexible ureterorenoscopy and lithotripsy of renal calculi was done in 8 patients (6.25%). Two of the eight patients had calculi refractory to ESWL and the rest had calyceal calculi predominantly in the lower calyx. The size of the renal stones treated was from 8mm to 1.5cm. All patients had stent insertion following lithotripsy. Stone visualization was possible in all cases but adequate fragmentation was possible only in 6 patients. The procedure was abandoned in 2 patients due to poor vision caused by bleeding. Subsequent passage of calculus occurred in 6 cases around the stent. Significant haematuria following flexible ureteroscopic lithotripsy of renal calculus was seen in two patient which settled in the post operative period without any intervention.In cases where ureteroscopy was done for indications other than calculus disease the results are as follows:- in cases of radiologically equivocal PUJ obstruction with symptoms, ureteroscopic balloon dilatation of PUJ with accent ureteral balloon dilator was done in 3 of the 5 cases. Following ureteroscopic identification of PUJ and passing a guide wire under vision through the PUJ, the ureteroscope is removed and the balloon catheter is threaded up the ureter over the guide wire across the PUJ with C-Arm control.

The exact position of the balloon was determined with the help of the radiopaque markers on the balloon catheter and by contrast injection through the lumen of the catheter. Balloon dilatation of the PUJ was done at 3 atmospheric pressure using an inflation device with pressure gauge for 5 minutes. The balloon was deflated and contrast injected through the channel of the balloon catheter. Contrast was seen to flow freely down the ureter across the PUJ around the sides of the balloon catheter. The balloon catheter was subsequently removed and replaced by 6 fr silicone double J stent which was kept indwelling for 4-65 weeks. In two lady patients, ureteroscopic endopyelotomy of the PUJ was done as it was possible to access the pelviureteric junction using a rigid ureteroscope. The posterolateral aspect of the PUJ was incised using retro cutting endoscissors & hook diathermy. Silicone double J stent as inserted following the procedure. This procedure is performed only in female patients as it is easy to access the PUJ on account of the short urethra. The procedure was attempted in one young male patient which failed due to the fact the ureter was tortuous and the PUJ could not be identified hence the scope could not be passed through the PUJ which is necessary for asuccessful endopyelotomy. The procedure was abandoned and an open Dismembered Pyeloplasty was done in the same sitting.

Strictures of the ureter were seen in 9 patients and were managed by visual dilatation in 3 patients and by balloon dilatation in 6 patients. One young lady presented with a long segment ureteric stricture (3cm) in the upper ureter of the left kidney. The stricture was a sequelae of urinary tuberculosis which was proved by a positive urine smear and culture for tuberculous bacillus. After starting Anti tuberculous reatment (ATT), ureteroscopic dilatation of the tight stricture was done and a 6 fr silicone double J stent was placed. The stent was retained for a year and the patient was given a full course of ATT. Following removal of the stent the kidney showed normal function on IVP and the strictured ureter healed around the stent and the obstruction was relieved. The patient is symptom free after the procedure (pain free). Stent migration was seen in two cases. Both the patients had placement of the stents elsewhere. The lower end of the stents should normally be present in the bladder. Due to faulty placements, the lower end of the stent stent migrates into the lower ureter and necessitates ureteroscopy for its removal. The migrated stents were successfully removed by ureteroscopy in both the cases. All non calculus procedures had stents placed after the procedure and kept for periods ranging from 3-6 weeks. Bil ureteroscopy were done in the same sitting in 3 patients with bilateral ureteric stones. In two of them the stones were fragmented and removed with placement of stents and in one the stone migrated to the kidney on one side. He was later sent for ESWL afterplacing a stent at the time of surgery.

Table 1. Results of Ureteric Stone Management by Ureteroscope

Total No of Cases - 81

|

NO |

RESULT |

NO OF PATIENTS |

PERCENTAGE |

|

1

|

Complete stone removal

|

58

|

71.6%

|

|

2

|

Partial stone removal

|

6

|

7.4%

|

|

3

|

Stone Migration

|

5

|

6%

|

|

4

|

Open surgery conversion

|

6

|

7.4%

|

|

5

|

Spontaneous passage

|

6

|

7.4%

|

Table 2. Intra-Operative Ureteric Injuries, Remedial Action Taken & Result

|

NO OF PATIENTS

(TOTAL - 13) |

TYPE OF INJURY |

REMEDIAL ACTION TAKEN |

RESULT |

|

Immediate |

Delayed |

|

1 |

Ureteric Avulsion |

Nephrostomy |

-- |

Subsequent ileal ureteric replacement

– doing well |

|

3 |

Small ureteric perforation |

JJ stenting in two patients |

Open surgery in one |

All doing well. Patient passed calculus in two cases. One removed during open surgery |

|

9 |

Minor Ureteric mucosal Abrasions |

JJ stenting |

-- |

No further treatment required

|

Table 3. Showing Comparative Results with Other Series

|

Results |

Our series |

Delepaul

Prog.Urol 26 |

P. Puppo

European Urology 1 |

Schultz.A

J.Urol 7 |

|

Total no cases |

128 |

379 |

378 |

100 |

|

Stone removal |

71.6% |

76% |

93% |

69% |

|

Ureteric avulsion |

0.7% (1) |

- |

.2% (1) |

- |

|

Ureteric perforation |

2.3% |

3.4% |

1.3% |

4% |

|

Failed procedure |

7% |

13.5% |

5.8% |

11% |

DISCUSSION

Hampton Young performed the first ureteroscopy in 1912 in an infant with massively dilated ureters using a cystoscope, which advanced easily to the renal pelvis.2 Marshall described fiberoptic ureteroscopy in 1964 and the first built ureteroscope was reported in 1979.3 The new generation small bore rigid and semi-rigid fiberoptic reteroscopes have become integral to the modern management of ureteric calculi. Open ureterolithotomy is rare except in a select sub-group of patients i.e. those with complex calculus disease associated with anatomic abnormalities. Ureteroscopy has become as effective as open surgery with little attendant morbidity.4, 5 Early intervention and relief of an obstruction precludes the development of renal obstructive complications. Also with modern lifestyles and demands of the work place, the patients’ prefer rapid diagnosis and early management of their problem.

At the Department of Urology, Sultan Qaboos Hospital, Salalah, the equipments available at our disposal are Olympus 8.6 Fr Semirigid Ureteroscope, (2nos) 6.4 Fr Semirigid Ureteroscope (one) and 8.4 Fr Flexible Ureterorenoscope (2nos). Visualization is by using endocamera. The energy source available is the Combilith which has both Electrohydraulic and Electrokinetic energy. The electrohydraulic component has been used principally with the flexible ureteroscope for purposes of lithotripsy of renal calculus as flexible 2 fr probes are available for use with the scope. The electrokinetic energy is used for stones in the ureter. Balloon dilators (Accent Ureteral Dilation Balloon Catheter, 5 Fr, 65cms, with 4mm balloon, 6cms long) were used in almost all cases where it was deemed necessary to dilate the ureteric orifice and also in patients with equivocal PUJ obstruction. For dilating a ureteric stricture the ureter the Marflow Transureteroscopic Balloon dilator 3.5 fr is used.

Ureteroscopy was done for both males and female patients in the ratio of 5.9:4.1. The procedure was done for calculus disease of the upper urinary tract in over 70% of cases. Most cases of ureteric calculi are managed by expectant therapy by way of increased fluid intake either orally or parenterally especially when they present with associated vomiting and need supplementation with intravenous fluids. Non steroidal anti inflammatory drugs like diclofenac sodium are used when pain is acute. When the pain is still not relieved then narcotic analgesics are used and these patients are admitted to the hospital. Recently we have started using Terazocin (an alpha blocker) in doses of 2 mg daily after studies proving their efficacy in aiding spontaneous stone passing was published in literature.6 This expectant therapy is instituted in patients with smaller calculi 5mm or less, which are expected to pass spontaneously and in patients who are not incapacitated by recurrent ureteric colic. These patients are followed up every two weeks and the stone progression is monitored by x-ray. Patients are taken up for ureteroscopic removal of the calculus when the size of the stone is over 6mm, in symptomatic patients’ frequently needing admission and non progressive stones with hydroureteronephrosis.

Figure 1: Semirigid Ureteroscope Figure 2: Flexible Ureterorenoscope

Majority of upper ureteric stones which were initially treated with ureteroscopy are at present sent for lithotripsy. ESWL is effective for upper ureteric calculi provided the calculus is radio opaque and is at least over 5mm in size to enable accurate focusing of the shock wave. The fragmented particles pass spontaneously. Rarely larger fragments get impacted in the lower ureter or the vesico ureteric junction and may require removal by cystoscope or ureteroscope. In female patient’s upper ureteric and mid ureteric calculi are still treated with ureteroscopy and lithotripsy. Our results of ureteroscopy for calculus disease of the ureter show a 71% successful outcome in the form of stone removal and on excluding the 6 cases where the stones passed spontaneously prior to the procedure the percentage goes up to 77%. This is comparable with a number of series which show stone clearance rate from 69% - 90%.7 The role of balloon dilatation of PUJ is an accepted procedure and is useful in selected cases of equivocal PUJ obstruction with intermittent pain.8

J.M. Lewis-Russell et al. have presented a 10 year experience in retrograde balloon dilatation of pelvi ureteric junction obstruction in the British Journal of Urology [feb 04] with symptomatic relief in 78% of cases.10 We had done 3 such cases and all have done well symptomatically and two have shown radiological improvement as well. Ureteroscopic incision of the PUJ (endopyelotomy) has been described .11 We have done two cases successfully.

Ureteroscopic management of strictures of the ureter has also been described and we successfully dilated and stented all 11 cases of strictures of the ureter encountered in our series.12 All strictures were short segment strictures < 1 cm long except in three cases the stricture ranged from 2-3 cm in length. Two of the three long segment strictures were dilated visually by passing the ureteroscope over the guide wire under vision. One patient had stricture at the ‘Y’ junction of an incomplete duplication of the ureter. The stricture in both the duplicated ureters was successfully dilated by ureteroscopy. Ureterorenoscopy for the treatment of refractory upper urinary tract stones was illustrated by Menezes, Dickinson & Timoney in their article published in BJU in august 1999.13,14 They have presented 37 cases of refractory renal calculus for which flexi ureterorenoscopy was done and lithotripsy of the calculus was done with Electrohydraulic Lithotripter (EHL). 75% of their patients improved symptomatically following the procedure with residual stone fragments of less than 5 mm. They advocate laser lithotripsy to EHL. In our series we have done 8 cases of ureterorenoscopy for renal calculi and successfully fragmented the stones in 6 cases (66%) and partially fragmented the stones in 2 cases and had to abandon the procedure due to poor vision caused by debris from the calculus and by bleeding which obscure proper visualisation. Following the procedure, 6 patients passed the stone fragments around the stent. Two were sent for ESWL. The most important complication that can occur during lithotripsy of renal calculi with EHL is haematuria and perforation. Haematuria can be gross at times. Care should be taken to place the probe only on the calculus without touching the renal tissue. In our experience significant haematuria was seen in two cases which settled spontaneously in two days time.

There is a controversy of placing stents following ureteroscopic procedures. Some centres routinely employ stents,15 since it reduces post operative pain which may arise due to ureteric meatal oedema as a result of ureteric meatal dilatation and reduces hospital stay. In our series only 42% of our cases had stents inserted. In cases where stent was deferred, severe post operative pain necessitating narcotic analgesics occurred in 30% which settled spontaneously in a day or two. Only 2 patients had to be taken up for stenting as the pain was persistent and severe and there was hydronephrosis.16 This is comparable with the other series described in the literature. Routine stenting is not necessary in all cases of ureteroscopy as the stent by itself can cause problems like dysuria, UTI, haematuria and migration. Though the data suggest a hospital stay of patients from 2 to > 10 days, it includes patients who get admitted for ureteric colic, get investigated and then undergo ureteroscopy as well as patients coming for elective procedure. Some patients were medically unfit and had to be treated prior to ureteroscopy. The average duration of hospital stay in our series after the procedure of ureteroscopy has been 3-5 days (>90%).

COMPLICATIONS

The complications encountered during ureteroscopy were as follows:

Major: There was single major complication (0.78%) namely a long segment ureteric avulsion during ureteroscopy. This occurred very early in our series. At that time we had only the 8.6 Fr semirigid ureteroscope and no balloon ureteric dilator. This was a case of a right sided mid ureteric calculus about 6-7mm in size for which rigid ureteroscopy was attempted. The stone was migrating upwards and lithotripsy was difficult. The stone was pursued and prolonged lithotripsy attempted. This led to trauma and a long segment ureteric avulsion which was recognized immediately and as the avulsed segment could not be repositioned, a nephrostomy was done. Subsequently the patient underwent reconstructive surgery in the form of ileal ureteric replacement. The patient is doing well four years after this complication and has a normal functioning right kidney. On retrospective study as to why the avulsion occurred it was evident that insufficient dilatation of the ureteric orifice had been done and subsequent passage of a larger scope to the upper ureter with attempted removal using dormia basket resulted in the scope being gripped by the ureter at the lower end and at the ureteric orifice which led to the avulsion of the ureter during removal of the ureteroscope at the site where the ureter was damaged by the lithotripter probe and dormia basket, about 4-5 cm below the pelviureteric junction. After that incident, balloon dilators were procured and in subsequent cases as a policy, migrating ureteric stones during ureteroscopy was left alone and the ureter stented. These patients are followed up with repeat x-rays and in majority of them, the stones descend again well into the lower ureter and repeat ureteroscopic removal is done. Stones which do not descend are managed by ESWL. Following this major complication early in our series, over a 100 cases has been done with no major complications. Ureteral avulsion has been described as an upper urinary tract injury occurring during endourological procedures and is applied to an extensive degloving injury resulting from a mechanism of stretching of the ureter that eventually breaks at the most weakened site. The first cases were reported by Hart in 1967,17 and Hodge in 1973,18 both after difficult manipulation of a ureteral stone. Although an infrequent event in the endoscopic management of ureteral calculi (0.2-1%) with only few cases reported in the literature, ureteral avulsion is a potential serious complication that should always be taken into account when performing such procedures. Among the potential factors involved in the pathogenesis of ureteral avulsion, the presence of a narrow ureteric orifice, either due to a disease or to previous endourological manipulations, is an important antecedent in the majority of cases. Furthermore, the use of dormia baskets for ureteral stones retrieval have also been implicated. Diagnosis of ureteral avulsion is most often made immediately during the endoscopic procedure after the recognition of a tubular structure firmly engaged to the ureteroscope following the extraction maneuvers.19 Traditionally the treatment of the ureteral avulsion has been a surgical approach, for which the basic aim is to restore the ureteral continuity. Nevertheless, clear guidelines about the best surgical technique are still an unresolved issue. There are some factors that should be taken into account, such as age of the patient, kidney function, level of injury, and length of the ureteral defect. In lower third ureteral lesions, a ureteral reimplantation seems the most rewarding surgical technique, but severe ureteral injuries associated with higher localization or loss of a long segment require several methods of repair, including boari flap, psoas hitch, transureteroureterostomy, autotransplantation, or ileal or appendix interposition. The use of a psoas hitch, a boari flap or a combination of both seems to be the most sensible option, but restricted to injuries at or below the pelvic brim. However, Chang & Koch described a modification of the traditional bladder flap procedure or extended spiral bladder flap for a successful treatment of two patients with upper ureteral injuries.20 In case of complete avulsion of the ureter at the ureteropelvic junction, a dismembered pyeloplasty is the preferred option. Incase of severe tissue loss, autotransplantation, especially in young patients, or ileal interposition,21, 22 will yield a satisfactory result. Moreover, an alternative method of successful repair of extensive injuries with appendix interposition was reported in three cases where the conventional techniques were precluded. Recently in an article published in British Journal of Urology in Feb 2005 the replacement of the ureter by an ileal tube,23 using the Yang-Monti procedure was very well illustrated. This new technique offers some distinct advantages. A short bowel segment is included, with the consequent absence of metabolic complications. It allows construction of an ileal ureter with a suitable cross-sectional diameter with no need for tailoring, and makes possible the use of an antireflux technique. Two centres with a large ureteroscopy series have presented 3 cases each of ureteric avulsion as a complication. In one series, two of the patients had nephrectomy eventually and only one had a successful outcome following reconstruction.19 In most series, ureteric avulsion occurred early in their series as in our case. Ureteral avulsion is a rare but well known complication of ureteroscopy, almost always related to the use of an ureteroscope too large to be readily accommodated by the ureter or, in most cases, by an attempt to pull an inadequately fragmented or impacted stone down from the proximal or mid ureter. The best treatment of ureteral avulsion as a complication of ureteroscopy is prevention. Subsequently a better approach and safer techniques have been adopted and no further major complication was encountered.

Minor: The minor complications encountered were, transient haematuria which occurred in 7 patients (5.4%) and in two of them it was significant following lithotripsy of renal calculus. The haematuria also settled spontaneously without need for transfusion or intervention. Small ureteric perforations occured in 3 patients (2.3%). Ureteric perforation was recognized and stented in two patients and in one case a very small perforation had occurred below an impacted upper ureteric stone during attempted lithotripsy using a flexible electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL) probe via the flexible ureteroscope. It was identified only when the patient subsequently underwent open surgery a few days later. There was minimal periureteric collection at the site of the stone. The perforation as such could not be visualized. After removal of the calculus a stent was placed from above and the patient had an uneventful recovery. Minor mucosal injuries and abrasions occurred in 9 patients (7%). Stone migration was seen in 5 patients (6%). Four of them were stented and sent for ESWL. One patient passed the stone without any intervention. Failure to stent the ureter following ureteroscopy, when deemed necessary occurred in 3 cases (2.3%). This was due to technical reasons like inability to pass the guide wire following ureteroscopy, due to mucosal dissection at the site of stone impaction, or kinking of the guide wire. This failure did not lead to any untoward effects in the post operative period. Ureteroscopy was abandoned in 9 of our cases (7%) due to poor vision because of bleeding or to insufficient ureteric meatal dilatation or failure to advance the scope due to kinking of ureter and failure of lithotripsy of hard calculi. In 6 cases of ureteric calculi, 2 cases of renal calculi and one case of PUJ obstruction, ureteroscopy was abandoned due to the above mentioned reasons. In 6 patients (7.4%) with ureteric calculus, conversion to open surgery was done. This was due to failure to access the ureter due to insufficient ureteric meatal dilatation in 3 patients, kinking of the ureter in one patient and failure to fragment the stone over 1 cm in size with the available lithotriptors in two patients. Minor complications such as small perforations and mucosal injuries when recognized can best be treated by placing a double J stent. In our series 12 such cases (3 cases (2.3%) of small ureteric perforation and 9 cases (7%) of mucosal injury) were treated by stent alone.24 Our complication rate is acceptable when compared to other series published.

CONCLUSION

Ureteroscopy is one of the major developments in Endourology. It has revolutionized management of upper urinary tract disorders which before the advent of the ureteroscope, was a difficult proposition often resorting to complex radiological investigations and invariably open surgical procedures with its attendant morbidity and mortality. Carefully performed, ureteroscopy is safe and minor problems that may occur during the procedure can be managed easily. Patients are benefited by lesser morbidity and shorter hospital stay. At the Department of Urology, Sultan Qaboos Hospital, Salalah, we have been performing these procedures for the past six years with results comparable with other published series.25

REFERENCES

-

Puppo P, Ricciotti G, Bozzo W, Introini C. Primary endoscopic treatment of ureteric calculi. Eur Urol. 1999; 36:48-52.

-

Young HH. A Pioneer in Pediatric Urology. J Urol 166:1415-1417.

-

Marshall VF. Fiber Optics in Urology. J Urol 1964; 91:110-114.

-

Ather MH, Paryani J, Memon A, Sulaiman MN. 10-year experience of managing ureteric calculi: changing trends towards endourological intervention — is there a role for open surgery? BJU International 2001; 88:173-177.

-

Harmon WJ, Sershon PD, Blute ML, Patterson DE, Segu JW. Ureteroscopy; current practice and long-term complications. J Urol 1997; 157:28–32.

-

Resim S, Ekerbicer H, Ciftci A. Effect of Tamsulosin on the number and intensity of ureteral colic in patients with lower ureteral calculus. International J Urol 2005; 12:615-620.

-

Schultz A, Kristensen JK, Bilde T, Eldrup J. Ureteroscopy results and complications. J. Urol 1987; 137:865-866.

-

O’Flynn K, Hehir M, McKelvie G, Hussey J, Steyn J. Endoballoon rupture and stenting for pelviureteric junction obstruction: Technique and early results. Br J Urol 1989; 64:572-574.

-

Webber RJS, Pandian SS, McClinton S, Hussey J. Retrograde balloon dilation pelviureteric junction obstruction:Long–term follow-up. J Endourol 1997; 11:239–242.

-

Lewis-Russell JM, Natale S, Hammonds JC, Wells IP, Dickinson AJ. Ten years’ experience of retrograde balloon dilatation of pelvi ureteric junction Obstruction. BJU international 2004; 93:360.

-

Goldfischer ER, Jabbour ME, Stravodimos KG, Klima WJ, Smith AD. Techniques of endopyelotomy. Br J Urol 1998; 82:1–7.

-

Osther PJ, Geertsen U, Nielsen HV. Ureteropelvic junction obstruction and ureteral strictures treated by simple high pressure balloon dilation. J Endourol 1998; 12:429-431.

-

Menezes, Dickinson & Timoney. Flexible ureterorenoscopy for the treatment of refractory upper urinary tract stones. BJU International 1999; 84:257.

-

Bagley DH, Huffman JL, Lyon ES. Flexible ureteropyeloscopy: diagnosis and treatment in the upper urinary tract. J Urol 1987; 138:280-285.

-

Jeong H, Kwak C, Lee SE. Ureteric stenting after ureteroscopy for ureteric stones: a prospective randomized study assessingsymptoms and complications. BJU International 2004; 93:1032-1034.

-

Al-Hammouri F,Al Kabneh A. Queen Rania Centre for Urology and Organ Transplant, King Hussein Medical Centre, Amman, Jordan. Stenting versus Nonstenting after Uncomplicated Ureteroscopy for Lower Ureteric Stone Management. Calicut Medical Journal 2005; 3:e6.

-

Hart JB. Avulsion of the distal ureter with Dormia basket. J Urol 1967; 97:62-63.

-

Hodge J. Avulsion of a long segment of ureter with Dormia basket. Br J Urol 1973; 45:328.

-

Alapont JM, Broseta E, Oliver F, Pontones JL, Boronat F, Jimenez-Cruz JF. Ureteral Avulsion as a complication of Ureteroscopy. Int Braz J Urol 2003; 29:18-23.

-

Chang SS, Koch MO: The use of an extended spiral bladder flap for treatment of upper ureteral loss. J Urol. 1996; 156:1981-1983.

-

Shokeir AA. Interposition of ileum in the ureter: a clinical study with long-term follow-up. Br J Urol 1997; 79:324-327.

-

Kochakarn W, Tirapanich W, Kositchaiwat S. Ileal interposition for the treatment of a long gap ureteral loss. J Med Assoc Thai 2000; 83:7–41.

-

Ghoneim M.A, Ali-El-Dein B. Replacing the ureter by an ileal tube, using the Yang-Monti procedure. BJU International 2005; 95:455.

-

Kramolowsky EV. Ureteral perforation during ureterorenoscopy. Treatment and management. J Urol 1987; 138:36–38.

-

Geavlete P, Georgescu D, Nit G, Mirciulescu V, Cauni V. Complications of 2735 Retrograde Semirigid Ureteroscopy Procedures: A Single-Center Experience. J Endourol 2006; 20:79-185.

-

Delepaul B, Lang H, Abram F, Saussine C, Jaqcmin D. Ureteroscopy for ureteric Calculi, 379 cases. Prog Urol 1997; 7:600-603.

|

|