| |

Introduction

Tuberculous mastitis is a rare clinical entity, reported as 3% of mammary lesions in India.1,2 It usually affects women from the Indian sub-continent and Africa. It often mimics breast carcinoma and pyogenic breast abscess clinically and radiologically, may both co-exist.2,3,4 Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) and surgical biopsy may also be inconclusive. Diagnosis is usually based on high index of suspicion, findings of granulomatous lesion with Langhans’ giant cells, tuberculosis culture and response to antitubercular therapy (ATT). We report a case of tuberculous mastitis presenting as breast abscess.

Case Report

A 30 year-old- female patient was admitted with history of right breast lump, pain and fever for 2 months. There was no history of weight loss or cough with expectoration. The patient had taken oral antibiotic treatment for 15 days. On general physical examination, no abnormality was detected. Examination of the right breast revealed a tender, ill-defined, irregular, firm to hard lump (15×12 cm), adherent to the breast tissue with cystic areas and areas of skin fixity, involving almost the entire breast, except the lower inner and part of the upper inner quadrant. Axillary and cervical, including supraclavicular lymph nodes were not enlarged. Respiratory system examination was unremarkable.

Her routine hematological examination revealed leukocytosis and neutrophilia. Her ESR was 58mm/1st hour. Chest radiograph was unremarkable. FNAC of the breast lump revealed granulomatous mastitis. AFB was negative. Mantoux test was positive. Pus culture revealed Staphylococcus aureus, sensitive to cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, amikacin, gentamycin and ciprofloxacin. Biopsy of the lump revealed breast parenchyma with granulomas comprising of epitheloid cells, lymphocytes, and Langhans’ giant cells, mixed with areas of hemorrhage and extensive fibrosis. AFB was negative, and there was no evidence of malignancy.

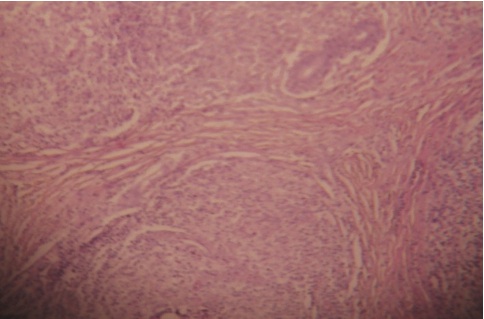

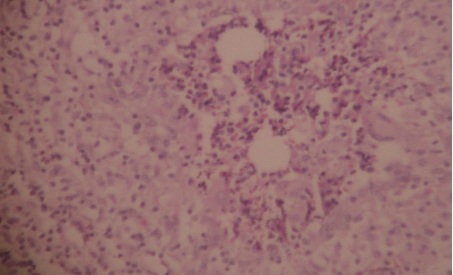

These features suggested granulomatous mastitis. In view of chronic abscess, incision and drainage (I&D) of abscess and biopsy was done under general anaesthesia. The patient was treated with 10 days of parenteral antibiotics ceftriaxone with amikacin. Subsequently, post- I&D wound, (Fig. 1) failed to heal and the patient developed multiple superficial abscesses/sinuses around the post- I&D wound. Biopsy revealed granulomatous mastitis with Langhans’ giant cell, (Fig. 2a and Fig. 2b).

Figure 1: Photograph showing non-healing post- I&D wound.

Figure 2a: Microphotograph showing granulomas with Langhans’ giant Cells (low power).

Figure 2b: Microphotograph showing granulomas with Langhans’ giant Cells (high power).

Culture revealed Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for tuberculosis was positive. Hence the patient was treated with ATT (INH, Rifampicin, Pyrazinamide and Ethambutol for 2 months; INH and Rifampicin for 7 months) for nine months. Local streptomycin powder was used for ulcer dressings. Ulcer and sinuses healed well, (Fig. 3a). The patient responded well to ATT without any residual lump. After 6 months follow up, the patient was asymptomatic. (Fig. 3b)

Figure 3a: Photograph after 2 months of ATT showing healed ulcer with sinuses.

Figure 3b: Photograph after completion of ATT, on 6months follow up.

Discussion

Tuberculosis of the mammary gland is a rare disorder often mistaken for other benign and malignant lesions of the breast. In India, the incidence of tuberculous mastitis has been reported to be between 1 - 4.5%.1,2 The first description of mammary tuberculosis was given by Sir Astley Cooper in 1829.5 Tuberculous mastitis is more commonly seen in females of reproductive age group, however, especially during the lactation period, when they are more susceptible since the lactating breast is more vascular and predisposed to trauma.4,5 Both breasts are reported to be involved with equal frequency. Bilateral disease is rare, occurring in 3% of patients.5 The duration of symptoms varies from a few months to several years, but in most instances, it is less than a year.

The most common symptom is a lump in the breast. Multiple lumps are less frequent. The classical presentation with multiple sinuses, ulcers, matted nodes and a breast mass is unfortunately less common, making clinical diagnosis difficult at times. Such a presentation is seen in less than 50% of all cases. Other uncommon presentations include; a typical undermined tuberculous ulcer, purulent discharge from the nipple or with a fluctuant swelling which, if inadvertently incised, produces a discharging ulcer.5,6

The lump in the breast in tuberculous mastitis is usually ill-defined, irregular, occasionally hard and indistinguishable from a carcinoma. Pain in the lesion is present more frequently than a carcinoma, often being a dull constant, nondescript ache. Involvement of nipple and areola, unless distinct, is rare in tuberculosis. Fixation to skin is frequent; however, the breast remains mobile unless breast involvement is secondary to tuberculosis of the underlying ribs. Regional lymph nodes may be enlarged. Lung lesions (active or healed) on radiographic examination are rare now. Mammography is of limited use since the findings are often indistinguishable from a malignancy.6 Co-existing tuberculosis and carcinoma of the breast was reported by Alzaraa et al.3 This patient had nipple retraction, peau d’ orange, and involvement of axillary lymph nodes.

Although it was initially believed that as much as 60% of breast tuberculosis was primary, it is now accepted that mammary tuberculosis is almost invariably secondary to a lesion elsewhere in the body. Primary infection of the breast however, through abrasions in the skin or through the duct openings on the nipple is a possibility. The most common mode of infection is thought to be retrograde lymphatic spread from the pulmonary focus through the para- tracheal and internal mammary lymph nodes. Hematogenous spread and direct extension from contiguous structures are other modes of infection.5

Breast tuberculosis was originally classified by McKeon et al7 into the following categories: (a) acute miliary type – rare, due to blood borne infection in miliary tuberculosis; (b) nodular type – the most common type, which presents as a localized lump with or without sinuses in one quadrant of the breast; (c) disseminated type – involving the entire breast with multiple sinuses; (d) sclerosing type – minimal caseation and extensive hyalinization of the stroma, shrinkage of the breast tissue with early skin retraction and late sinus formation; clinically this type is indistinguishable from carcinoma; and (e) tuberculous mastitis obliterans – a rare form due to intra ductal infection with fibrosis and obliteration of the ductal system; sinus formation is infrequent.4, 5, 7

The demonstration of acid fast bacilli (AFB) from the lesions is usually difficult.8 In tuberculous mastitis, the bacilli are isolated in only 25% of cases, and AFB are identified only in 12% of the patients. Therefore, demonstration of caseating granulomas with Langhans’ giant cells from the breast tissue and involved lymph nodes may be sufficient for the diagnosis. In tuberculosis-endemic countries, the finding of granuloma in FNAC warrants empirical treatment for tuberculosis even in the absence of positive AFB and without culture results. 8, 9 Detailed histological evaluation is, however, mandatory to rule out a co-existing carcinoma. FNAC is very useful and it is a promising technique in expert hands.9 A biopsy is mandatory for confirmation of diagnosis. All patients should receive adequate systemic chemotherapy (ATT). Local streptomycin has been claimed useful.5 After complete ATT, residual lumps localized to a quadrant should be excised via segmental or sector mastectomy. Aspiration or surgical drainage may be required in some cases. In extensive cases, a simple mastectomy has been advocated. Radical mastectomy is best avoided unless there is a co-existing malignancy.5,6

Conclusion

To conclude, diagnosis of tuberculous mastitis is usually based on high index of suspicion, finding of granulomatous lesion with Langhans’ giant cells and response to ATT. FNAC and biopsy may also be inconclusive. AFB is not seen in most cases. Prompt diagnosis and adequate treatment can avoid unnecessary operation in these patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors reported no conflict of interest and no funding has been received in this work.

|

|