Nowadays, the concept of health literacy has gained increasing attention in the public health arena due to its central role in determining public and individual health.1 Health literacy is broadly defined, from a focus only on reading and understanding of basic health information to a critical appraisal of health-related information and applying it to make sound decisions concerning health in daily life.2,3 Inadequate health literacy is associated with a myriad of health-related outcomes, including decreased comprehension of medical information, decreased self-care abilities, sub-optimal utilization of disease prevention services, increased risk of development of chronic diseases, and increased risk of morbidity and mortality.1,4

Along with the increasing attention in health literacy on a national and international level, there has been a growing demand regarding the development of valid and reliable tools to measure health literacy.5 Over the past years, many scales have been developed to assess health literacy.6–10 But critical appraisal of health literacy scales showed that limited empirical evidence exists on the content validity of health literacy measures. Based on the results of this critical appraisal, the content of current widely used measures of health literacy varied widely, and none appeared to fully measure a person’s ability to seek, understand, and use health information.11 Indeed, the content of almost all measures of health literacy was focused primarily on reading comprehension and numeracy. On the other hand, these scales have been developed extensively in clinical populations in developed countries.12 There is a need to develop new comprehensive health literacy instruments that incorporate broader constructs of health literacy,11 and to develop new indices that are tailored to different cultural populations.

Nutbeam argues that the concept of health literacy goes beyond focusing predominantly on the basic reading and numerical tasks required to be able to function effectively in everyday situations. Nutbeam describes health literacy as different sorts of cognitive, interpersonal, and social skills, which might determine a person’s ability to optimally manage their health and achieve their desired outcomes. Nutbeam suggests that the concept of health literacy can be divided into three domains: functional, communicative, and critical skills.3 Functional health literacy refers to basic literacy skills (reading and writing); communicative health literacy with the distinct abilities necessary to extract information and derive meaning from various communication channels; and critical health literacy refers to critical appraisal of health-related information and applying it to make sound decisions concerning health in daily life.3

To the best of our knowledge, there is no culturally adapted tool to assess functional, communicative, and critical health literacy in the general population of Iranian adults. Persian culturally adapted health literacy measures with good psychometric properties are necessary to compare or pool results across studies. So, this study describes the process of development and validation of the Functional, Communicative and Critical Health Literacy (FCC-HL) Questionnaire in Iranian general populations. Having a sound measure of health literacy can be used to establish benchmarks for policy and program development aimed at addressing inadequate health literacy.

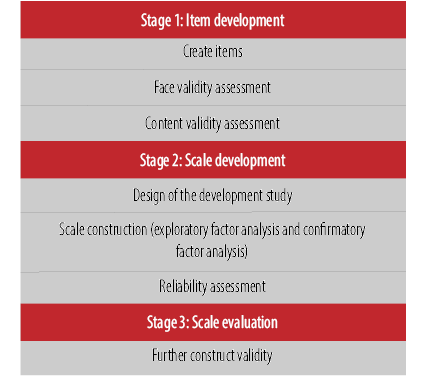

Figure 1: Scale development process following the procedure outlined by Schwab.

Methods

The scale development process followed the procedure outlined by Schwab in 1980.13 The scale development process included three basic stages: item development, scale development, and scale evaluation [Figure 1].

We used a deductive approach for stage one, item development. Deductive scale development utilizes a classification scheme before data collection. This approach requires a theoretical definition of the construct under examination to guide the development of items.13 In this study, Nutbeam’s definition was used as a theoretical definition of health literacy. The item development process began with a comprehensive review of published research on Nutbeam’s definition of health literacy and its measurement.1,3,10,12,14–16 Also, we conducted two focus groups to gain a comprehensive understanding of the functional, communicative, and critical health literacy needs in the context of Iranian adult population and to propose items related to the three skill domains. The focus groups included experts in health education and promotion, health literacy, community health, epidemiology, and medicine. After comprehensively analyzing Nutbeam’s definition of health literacy, 21 items were generated across three subscales with a seven-point Likert scale (certainly no to certainly yes response options). We used a seven-point Likert scale, because measures with five- or seven-point scales have been shown to create variance that is necessary for examining the relationships among items and scales and create adequate coefficient alpha (internal consistency) reliability estimates.17

In the next step, the face validity of the initial questionnaire was determined by asking the opinions of a sample of the target group. Fifteen individuals randomly selected from the target group presented their views about the importance of the items on a five-point Likert scale (5 = very important, 4 = important, 3 = averagely important, 2 = slightly important, and 1 = not important). Then, the quantitative method of impact score was used to determine the importance of each item. Questions that received a score more than 1.5 were retained for subsequent analyses.18

In the next step, theoretically generated derived items were subjected to a content validity assessment (content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI)) by a panel of experts (six health educators, two epidemiologists, and two physicians). The panel of experts reviewed the draft version of the questionnaire, and their opinions were captured in the final questionnaire’s contents. For calculating the CVR, the experts rated each item of the questionnaire on a three-point Likert scale (1 = necessary, 2 = helpful but not necessary, and 3 = not necessary). Calculated ratios for each item were compared with the numbers provided by Lawsche.19 If the calculated value was greater than the number given in Lawsche table (i.e., CVR values > 0.62), the item was considered as necessary and was retained for subsequent analysis. We used Lynn’s descriptive method (item-CVI) to calculate the CVI amounts.20 The experts were asked to rate each item based on simplicity (1 = not simple to 4 = very simple), relevance (1 = not relevant to 4 = very relevant), and clarity (1 = not clear to 4 = very clear) on the four-point scale. Based on the Lynn's method, if the number of experts was six or more, the I-CVI should not be less than 0.78.20

Stage two was scale development, which began with the study design. The study was carried out from April to September 2017 in Birjand city (Center of South Khorasan Province, east Iranian province, which borders Afghanistan). Study participants were a sample of the adult population aged between 18 and 60 years old. Per Hinkin’s review study, a sample of 150 was the minimum acceptable for scale development procedures.21 Also, a minimum sample size of 150 should be sufficient for exploratory factor analysis (EFA).22 For confirmatory factor analysis, a minimum sample size of 200 has been recommended.23 Our sample size was considered at least 350 people, but questionnaires were completed for 500 people. A cluster sampling design was used for data collection. In the first stage, 500 postal area codes were acquired from Birjand post office. These postal codes areas were considered as clusters. Then Birjand city was divided into 500 clusters, and households were selected randomly in each of these areas. In each household, one eligible person was selected. At first, the interviewer briefly explained the purpose of the survey. Also, confidence was given to each person including its anonymous and voluntary nature. Then, interviewers completed the initial health literacy questionnaires in people’s homes from those who verbally consented to participate. Each interview lasted about 5–10 minutes. Two trained research assistants administered the interview.

We then constructed the scale. Data were randomly split into half to conduct factor analysis. Then, the initial health literacy questionnaire was subject to independent exploratory (n = 250, mean age = 33.9±12.4 years) and confirmatory (n = 250, mean age = 32.8±11.8 years) factor analysis. The sociodemographic characteristics of the two samples were compared using independent sample t-tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). No statistically significant differences were found (p > 0.050).

SPSS (SPSS Inc. Released 2009. PASW Statistics for Windows, Version 18.0. Chicago: SPSS Inc.) was used to perform EFA. Before conducting the factor analysis, the internal consistency of the scale was examined. Our criterion for verifying the reliability of the instrument was Cronbach α > 0.70.24 Also, Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) was used to ensure the adequacy of sample size. If the KMO value was ≥ 0.5, the sample size was considered adequate.25 Bartlett’s test of sphericity was also examined.25 Then, principal axis factoring (PAF) using varimax rotation procedure was used to explore the dimensionality of the correlation matrices. Several main criteria were used to decide upon the factor structure: (a) Kaiser’s criteria (eigenvalue > 1 rule),26 (b) the scree test,27 and (c) parallel analysis by Monte Carlo PCA.28

AMOS software (version 18; AMOS Development Corp., Crawford, FL, USA) was used to assess the quality of the factor structure by statistically testing the significance of the overall model. There are several statistics that can be used to assess goodness of fit. According to Hu & Bentler (1999), the following indices were used to assess the goodness of fit of the health literacy questionnaire: Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), the normed χ2(χ2/df), and Parsimonious normed fit index (PNFI). The following cut-offs were used for acceptable fit: TLI = 0.90, CFI = 0.90, RMSEA ≤ 0.08, normed χ2 < 5, and PNFI = 0.50.29

Finally, to evaluate the reliability of the health literacy items, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated for the health literacy total scores and the three subscales. An alpha of 0.70 was considered the minimum acceptable standard for demonstrating internal consistency.24

Stage 3 was scale evaluation. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis and reliability assessment provide good evidence of construct validity, but further evidence of construct validity can be accomplished by demonstrating the existence of relationships with other variables that are theorized to be outcomes of the new measure (criterion-related validity, i.e., scale evaluation). It is also useful to assess the extent to which the scale correlates with other measures of constructs that theoretically should be related measures designed to assess similar constructs (convergent validity) and to which they do not correlate with measurements that are supposed to be unrelated (discriminant validity).21 We assessed construct validity using bivariate analysis between the total scores on the FCC-HL and theoretically relevant variables, including participants’ age, gender, educational level, history of smoking and alcohol consumption, self-rated household income, self-rated health, and self-rated health literacy.

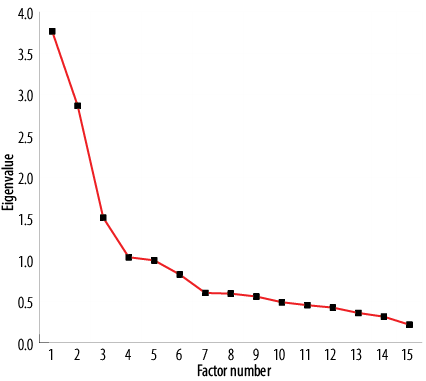

Figure 2: Scree plot for principal axis factoring of the health literacy questionnaire (n = 250).

Results

In the first step, the face validity of the initial questionnaire was determined by calculating the impact score index. Based on the rating that the target group assigned to each item, three items received a score of < 1.5 and were excluded for the next analysis. Cognitive testing revealed that 18 retained items were well understood and only some re-wording was required. In the next step, generated theoretically derived items were subjected to a content validity assessment by panel of experts. Based on the rating that experts assigned to each item, a CVR was calculated. The calculated ratios for three items were < 0.62, so these items were considered unnecessary and were excluded for subsequent analysis. Then, the CVI was determined. Each of the final 15 items achieved a CVI of > 0.80, suggesting strong agreement among the judges, and therefore high content validity.

After face and content validity, the final version of the FCC-HL questionnaire was subjected to independent exploratory (n = 250, mean age = 33.9±12.4 years) and confirmatory (n = 250, mean age = 32.8±11.8 years) factor analysis. With four items for functional health literacy, five items for communicative health literacy, and six items for critical health literacy, this 15-item questionnaire was rated on a range of 1–7 (certainly no to certainly yes) for each item. The scores for the items in each subscale were summed and divided by the number of constituting items in the subscale to give a score. Scores were reversed for functional health literacy, with higher scores indicating higher levels of health literacy.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the study participants’ demographic information. The mean age of participants was 33.3±12.1 years, ranging from 18 to 65 years. Of the 500 participants, 58.6% were female and 64.2% were married. Only 2.6% were illiterate and 47.6% had attended college. Most participants (75.2%) evaluated their health status as moderately good to good. In addition, only 6.6% of respondents had a history of smoking and 5.0% a history of alcohol use. Most respondents (81.4%) evaluated their income situation as moderate to good.

Before conducting the factor analysis, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated as 0.798. Also, the correlation matrix was considered to be factorable (KMO = 0.774, Bartlett’s test of sphericity = 1232.0, p < 0.001). PAF with varimax rotation produced three factors with an eigenvalue > 1 that explained 44.2% of the extracted variance. Item 8 cross-loaded onto more than one factor, as loadings were > 0.3 for both factors [Table 1]. This item was dropped from the final scale to address this issue. The scree plot suggested a four-factor solution [Figure 2]. This result was not obtained by parallel analysis that was conducted using Monte Carlo software. Indeed, PA in accordance with the eigenvalue > 1 rule, suggested a three-factor structure. Since the structure of three factors was also more consistent with the theoretical foundations of research, this structure was maintained. Item loadings from PAF of the FCC-HL, percentage of variance accounted for by each factor, and the Cronbach’s alpha of the factor items are shown in Table 1.

As shown in Table 2, a three-factor CFA model was fitted to these items. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient values were calculated to examine the internal consistency of the scale and its component subscales. For the resulting 14-item scale, internal consistency was good (α = 0.798). Also, it has adequately high internal consistencies of functional (α = 0.900), communicative (α = 0.803), and critical (α = 0.703) health literacy.

Table 1: Item loadings from principal axis factoring of the health literacy (HL) questionnaire (n = 250).

|

1 |

Imagine because of a disease the doctor has advised you to undergo surgery as soon as possible. Prior to the operation, you are asked to complete some forms such as the consent form. Do you need help from others to complete these forms? |

0.690 |

- |

- |

|

2 |

Imagine you are contacted by the Health Service Center and you are invited to participate in a series of health-related training courses. Before participating in this training program, you need to read some forms, such as a form of informed consent, that includes the goals of the educational program and ethical considerations related to the work and sign it if you consent. Do you need help from others to study these forms? |

0.754 |

- |

- |

|

3 |

Imagine sitting at home that suddenly the doorbell rings. The referral is a public health student who is completing a series of questionnaires for his research work. He/she asks you to participate in his/her research project and complete one of the questionnaires. Do you need help from others to complete this questionnaire? |

0.793 |

- |

- |

|

4 |

Imagine getting to the Health Service Center for periodic health care. A health worker gives you a pamphlet or brochure for various health topics to read at home. Do you need help from others to study this material? |

0.878 |

- |

- |

|

5 |

Imagine visiting a doctor because of a health problem. When the doctor explains about your illness, its treatment and the prescription drugs, unfortunately, you do not understand parts of his statements. Do you want him to repeat his explanations again to understand more? |

- |

0.671 |

- |

|

6 |

Imagine being hospitalized for an illness. The medical staff is constantly getting you different tests without giving any explanation. You do not understand the need for all these different tests and you have some questions about your treatment process. Do you ask the questions in your mind to the medical staff? |

- |

0.790 |

- |

|

7 |

Imagine taking part in a healthy nutrition class. At the end of the class, the health worker wants you to ask questions about the topic of the class. If you have questions about the topic, do you ask your question? |

- |

0.605 |

- |

|

8 |

Imagine visiting a doctor for an illness. At the end of the visit, the doctor provides you with some health advice. Do you put the doctor’s recommendations in a nutshell to make sure you understand his recommendations well? |

- |

0.301 |

0.452 |

|

9 |

Imagine having a health problem and getting to the Health Service Center for taking advice. After expressing your problem to the health worker, you feel that he does not quite understand your problem. Do you do all your best to make sure the health worker understands your problem properly? |

- |

0.545 |

- |

|

10 |

Imagine you are overweight. For weight loss, you try your best and seek information about ways to lose weight from various sources (the internet, friends and acquaintances, health care system, etc.). Do you try to check out the validity of information obtained from different sources? |

- |

- |

0.332 |

|

11 |

Imagine you or one of your acquaintances has a health problem. Do you search for experts that can best solve your problem? |

- |

- |

0.396 |

|

12 |

Imagine being completely healthy and not having any health problems. Do you look for the health-related information even in your healthiness? |

- |

- |

0.715 |

|

13 |

Imagine taking part in an election to choose representatives for political affairs (such as the presidential, parliamentary, and city council elections). Do you consider the level of candidates’ attention to public health issues when choosing these people? |

- |

- |

0.575 |

|

14 |

Imagine there are a lot of sanitary problems in your neighborhood. The Health Service Center invites you and your neighbors to discuss the sanitary problems in your neighborhood. Will you attend this meeting? |

- |

- |

0.498 |

|

15 |

Imagine there are a lot of sanitary problems in your neighborhood. Do you try to inform the health authorities about these problems? |

- |

- |

0.550 |

|

Percentage of variance explained |

21.322 |

16.435 |

6.486 |

Note. Item loadings lower than 0.300 not shown for clarity of exposition.

Extraction method: principal axis factoring. Rotation method: varimax with Kaiser normalization.

Table 2: Fit indices for confirmatory factor analysis of the health literacy questionnaire (n = 250).

FCC-HL: functional, communicative and critical health literacy; df: degrees of freedom; RMSEA: root mean-square error of approximation;

TLI: Tucker-Lewis index; CFI: comparative fit index; PNFI: Parsimony normed fit index.

χ2/ df: normed χ2.

Table 3: Bivariate relationships of health literacy (HL) questionnaire scales with other measures.

|

Age, years |

≤ 20 |

20.1 ± 6.6ab |

31.1 ± 7.3 |

21.6 ± 5.2 |

72.8 ± 14.1ab |

|

21–30 |

22.0 ± 6.0b |

32.9 ± 6.4 |

22.95 ± 5.0 |

77.9 ± 11.8a |

|

31–40 |

20.6 ± 7.2b |

33.0 ± 6.9 |

23.0 ± 5.0 |

76.7 ± 13.8ab |

|

41–50 |

17.3 ± 7.7ac |

32.1 ± 7.4 |

22.8 ± 5.3 |

72.3 ± 13.9ab |

|

≥ 51 |

16.2 ± 9.1c |

33.0 ± 6.7 |

22.5 ± 5.3 |

71.8 ± 14.7b |

|

p-value |

< 0.001 |

0.370 |

0.450 |

0.001 |

|

Gender |

Male |

20.8 ± 7.1 |

32.6 ± 7.0 |

22.4 ± 5.3 |

75.8 ± 13.5 |

|

Female |

19.8 ± 7.4 |

32.6 ± 6.7 |

23.0 ± 4.9 |

75.4 ± 13.3 |

|

p-value |

0.150 |

0.950 |

0.230 |

0.760 |

|

Educational level |

Illiterate |

5.2 ± 3.3a |

27.3 ± 9.0a |

22.2 ± 4.7 |

54.7 ± 13.5a |

|

< Diploma |

18.5 ± 7.8b |

31.9 ± 6.8b |

22.8 ± 5.0 |

54.7 ± 13.5b |

|

Diploma |

20.1 ± 7.0b |

32.1 ± 7.1b |

22.4 ± 4.8 |

74.7 ± 12.9b |

|

Attended college |

21.8 ± 6.2b |

33.5 ± 6.3b |

23.0 ± 5.2 |

78.4 ± 12.2b |

|

p-value |

< 0.001 |

0.004 |

0.670 |

< 0.001 |

|

Self-rated household income |

Low |

17.0 ± 8.9a |

29.7 ± 7.8a |

22.3 ± 5.1 |

69.0 ± 15.1a |

|

Moderate |

19.8 ± 7.0ab |

33.0 ± 6.6b |

22.7 ± 5.0 |

75.6 ± 12.9ab |

|

Good |

21.5 ± 6.6b |

33.3 ± 6.4b |

23.0 ± 5.2 |

77.9 ± 12.5b |

|

Perfect |

23.1 ± 5.7b |

32.5 ± 6.8ab |

21.8 ± 4.4 |

77.5 ± 11.6b |

|

p-value |

< 0.001 |

0.001 |

0.680 |

< 0.001 |

|

Self-rated health |

Weak |

14.8 ± 8.9a |

27.6 ± 7.4a |

22.7 ± 5.3 |

65.2 ± 14.3a |

|

Moderately good |

20.0 ± 7.4b |

33.2 ± 6.4b |

23.0 ± 4.8 |

76.2 ± 12.9b |

|

Good |

20.4 ± 6.9b |

32.7 ± 6.5b |

22.5 ± 5.1 |

75.7 ± 15.6b |

|

Perfect |

21.7 ± 6.6b |

33.4 ± 7.3b |

22.7 ± 5.6 |

77.9 ± 14.1b |

|

p-value |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

0.850 |

< 0.001 |

|

History of smoking |

Yes |

19.3 ± 7.3 |

30.7 ± 7.5 |

21.0 ± 5.3 |

71.0 ± 13.6 |

|

No |

20.3 ± 7.3 |

32.7 ± 6.7 |

22.8 ± 5.1 |

75.9 ± 13.3 |

|

p-value |

0.450 |

0.090 |

0.040 |

0.040 |

|

History of alcohol |

Yes |

22.8 ± 6.4 |

30.8 ± 8.3 |

19.6 ± 6.9 |

73.3 ± 14.1 |

|

No |

20.1 ± 7.3 |

32.7 ± 6.7 |

22.9 ± 5.0 |

75.7 ± 13.3 |

|

p-value |

0.070 |

0.170 |

0.030 |

0.400 |

|

Weak |

13.3 ± 8.9a |

26.6 ± 7.7a |

20.4 ± 6.1a |

60.4 ± 14.1a |

|

Moderately good |

20.5 ± 7.0b |

32.7 ± 5.8b |

23.4 ± 4.2b |

76.6 ± 11.6b |

|

Good |

20.7 ± 6.9b |

33.0 ± 6.4b |

23.0 ± 4.9b |

76.8 ± 12.3b |

|

Perfect |

20.8 ± 7.0b |

33.4 ± 7.8b |

21.8 ± 6.1ab |

76.1 ± 15.0b |

Note. a, b, c, ab, and ac are indices showing results of post-hoc Tukey test.

Similar indices for each variable indicate that individuals are in the same category in terms of that characteristic.

SD: standard deviation.

The total health literacy score averaged at 75.5±13.3, and the mean subscale scores were 20.2±7.3 for functional health literacy, 22.7±5.1 for communicative health literacy, and 32.6±6.8 for critical health literacy. ANOVA was used to detect differences between subgroups of each sociodemographic factor and its relationships with each domain of FCC-HL. Bivariate analysis between health literacy and three health literacy scores with theoretically relevant variables are shown in Table 3. Total scores on the FCC-HL were significantly and positively associated with participants’ age, educational level, self-rated household income smoking history, self-rated health, and self-rated health literacy. No association was seen with FCC-HL and gender.

Discussion

Unfortunately, despite a growing demand regarding the development of valid and reliable tools to measure health literacy,5 research using a theory-driven approach to develop health literacy questionnaires is limited. We used Nutbeam’s theoretical definition of health literacy as a framework to develop and test a new measure of health literacy.3 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to develop a FCC-HL questionnaire and test its efficacy in the general population of Iranian adults. The results we obtained indicate that this newly constructed health literacy tool is highly valid and reliable.

Functional health literacy is concerned with the basic literacy skills of reading and writing.3 Over the past years, many scales have been developed to assess functional health literacy.6–8 These scales were focused primarily on reading comprehension and numeracy in clinical populations in developed countries.12 The concept of functional health literacy can go beyond the hospital or doctor’s consulting room.30 So in our study, instead of focusing only on basic literacy skills of reading and writing in clinical populations, we developed functional items based on the most important situations that Iranian adults may need to use these basic skills. These items examine how Iranian adults engage with written health material in socially situated literacy events. For example, one of the most important aspects of functional health literacy in Iran can be the ability of individuals to read and understand written health materials that are widely used in Iran’s health system. In Iran, one of the main centers for providing preventive health services is comprehensive health centers, which provide educational services. Since the workload is high in most of these centers, in many cases, health workers give people written materials such as pamphlets or brochures for various health topics to read at home. Therefore, it is very important that the Iranians can read and understand these written health materials.

On the other hand, one of the most common methods for collecting health information in Iran is the use of self-administered questionnaires. So, another aspect of functional health literacy in Iran is the ability of individuals to read and complete these questionnaires. Considering the above and based on the comprehensive review existing questionnaires and the opinion of the experts, we initially designed seven items to measure functional health literacy in different situations (i.e., clinical situations, preventive health services centers, and everyday activities). Of these, two items were excluded in the face validity stage because of the target group’s opinion about their non-importance. Also, one item was excluded in the content validity stage based on expert opinions. Finally, the functional health literacy scale included four items. These items asked whether the participant would be able to: (I) read and complete some forms such as the consent form in medical and preventive settings; (II) read and understand written educational health materials; and (III) read and complete self-administered health questionnaires.

Communicative health literacy refers to distinct interpersonal and social skills necessary to extract information and derive meaning from different forms of communication.3 In this study, we initially designed seven items to measure an individual’s skills and confidence for constructive interactions with healthcare providers and the ability to negotiate within the healthcare system. Of these, one item was excluded in the face validity stage and one item was excluded in the content validity based on opinions about their necessity. Also, one item was excluded in the EFA because of cross loading onto more than one factor leaving four items. These items asked whether the participant would be able to extract understandable health-related information from different health care providers.

Finally, critical health literacy refers to higher-level cognitive and social skills required to critically appraise health-related information and applying it to exert greater control over life events and situations.3 The concept of critical health literacy can be divided into three domains: the critical analysis of information, an understanding of the social determinants of health, and engagement in collective action.31 Some health literacy researchers have assessed critical health literacy defined in terms of information appraisal by using a short questionnaire to ask respondents the extent to which they consider the validity and credibility of health information.10,14 On the other hand, some researchers have assessed critical health literacy as an individual’s ability to understand the social determinants of health by using questions about perceived reasons for poor health and health inequalities.32,33 Similarly, Freedman et al,34 emphasize the importance of the involvement of the individual or the community in the social determinants of health as ‘public health literacy’. Critical health literacy was also assessed by measuring collective socio-political action.31 Health literacy researchers have made little progress in specifying exactly what these collective socio-political competencies might be and determining how they might be measured.31 However, collective action can be considered as citizen competencies such as informed voting behaviors, knowledge of health rights, advocacy for health issues, and membership of patient and health organizations.31,35

Considering the above, we attempted to design a full breadth of items to measure critical health literacy. We initially designed seven items to measure critical health literacy, from whom one item was excluded in the content validity stage giving a total of six items. These items assess: (I) the individual’s ability to determine the credibility of health information obtained from different sources such as the internet, friends, and health care system; (II) the individual’s ability to determine the credibility of experts that can best solve their health problems; (III) the individual’s ability to make beneficial decisions beyond one’s own health; and (IV) the individual’s sensitivity to health problems in neighborhoods and community.

It is important to note that the participants in this study were exclusively adults from southern Khorasan; thus, cross-validation of the study in larger and more nationally representative populations is necessary before making any claims regarding the generalizability of the instrument. Due to the cross-sectional nature of this study, we could not investigate the causal relationship between health literacy and health outcomes. Prospective studies are needed to evaluate the predictive validity of the scale with regards to health outcomes, and to offer convincing evidence that applying this newly constructed health literacy tool is worthwhile in predicting health outcomes. Also, our designed questionnaire may not cover the whole concept of the functional, communicative, and critical health literacy as defined by Nutbeam. Moreover, we did not check the association between our measure and other standardized measures of health literacy (such as TOFHLA and REALM) as a way of exploring the construct validity of the FCC-HL.

Conclusion

Much of the existing tools to measure health literacy focused on functional health literacy within the context of the clinical setting. So, we developed the FCC-HL questionnaire to measure the health literacy of general populations and not specific patient groups. Also, it does not only assess functional health literacy but captures a broader concept of health literacy. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to develop a FCC-HL tool and test its efficacy in the general population of Iranian adults. The results we obtained indicate that this newly constructed tool is highly valid and reliable. We expect that the FCC-HL questionnaire will be useful in population surveys and studies of interventions. However, there is a need to confirm the usefulness of this new health literacy instrument in other cultural settings. On the other hand, the associations between scores on health literacy with other theoretically driven variables described above suggest that health providers should be cautious in making assumptions about the health literacy competencies of different community members.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this study.

Acknowledgements

This research has been made possible by support from the Birjand Social Determinants of Health Research Center. The authors wish to thank our expert panel members for their contribution to this project. We would also like to thank Deputy of Research and Technology of Birjand University of Medical Sciences for cooperation with the project. Also, we would sincerely like to thank participants involved in this study for their support and co-operating anonymously.

references

- 1. Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc Sci Med 2008 Dec;67(12):2072-2078.

- 2. Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, Doyle G, Pelikan J, Slonska Z, et al; (HLS-EU) Consortium Health Literacy Project European. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012 Jan;12(1):80.

- 3. Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int 2000;15(3):259-267.

- 4. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011 Jul;155(2):97-107.

- 5. Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Pelikan JM, Fullam J, Doyle G, Slonska Z, et al; HLS-EU Consortium. Measuring health literacy in populations: illuminating the design and development process of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). BMC Public Health 2013 Oct;13(1):948.

- 6. Davis TC, Crouch MA, Long SW, Jackson RH, Bates P, George RB, et al. Rapid assessment of literacy levels of adult primary care patients. Fam Med 1991 Aug;23(6):433-435.

- 7. Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med 1995 Oct;10(10):537-541.

- 8. Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, Mayeaux EJ, George RB, Murphy PW, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med 1993 Jun;25(6):391-395.

- 9. Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, Castro KM, DeWalt DA, Pignone MP, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med 2005 Nov-Dec;3(6):514-522.

- 10. Ishikawa H, Nomura K, Sato M, Yano E. Developing a measure of communicative and critical health literacy: a pilot study of Japanese office workers. Health Promot Int 2008 Sep;23(3):269-274.

- 11. Jordan JE, Osborne RH, Buchbinder R. Critical appraisal of health literacy indices revealed variable underlying constructs, narrow content and psychometric weaknesses. J Clin Epidemiol 2011 Apr;64(4):366-379.

- 12. Nutbeam D. Defining and measuring health literacy: what can we learn from literacy studies? Int J Public Health 2009;54(5):303-305.

- 13. Shawab D. Construct validity in organizational behavior. Res Organ Behav 1980;2:3-43.

- 14. Ishikawa H, Takeuchi T, Yano E. Measuring functional, communicative, and critical health literacy among diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2008 May;31(5):874-879.

- 15. van der Vaart R, Drossaert CH, Taal E, ten Klooster PM, Hilderink-Koertshuis RT, Klaase JM, et al. Validation of the Dutch functional, communicative and critical health literacy scales. Patient Educ Couns 2012 Oct;89(1):82-88.

- 16. Chinn D, McCarthy C. All Aspects of Health Literacy Scale (AAHLS): developing a tool to measure functional, communicative and critical health literacy in primary healthcare settings. Patient Educ Couns 2013 Feb;90(2):247-253.

- 17. Lissitz RW, Green SB. Effect of the number of scale points on reliability: A Monte Carlo approach. J Appl Psychol 1975;60(1):10.

- 18. Cook DA, Beckman TJ. Current concepts in validity and reliability for psychometric instruments: theory and application. The American journal of medicine. 2006;119(2):166. e7-166. e16.

- 19. Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity1. Person Psychol 1975;28(4):563-575.

- 20. Lynn MR. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res 1986 Nov-Dec;35(6):382-385.

- 21. Hinkin TR. A review of scale development practices in the study of organizations. J Manage 1995;21(5):967-988.

- 22. Guadagnoli E, Velicer WF. Relation of sample size to the stability of component patterns. Psychol Bull 1988 Mar;103(2):265-275.

- 23. Hoelter JW. The analysis of covariance structures: goodness-of-fit indices. Sociol Methods Res 1983;11(3):325-344.

- 24. Nunnally JC, Bernstein I. Psychometric theory. New York: MacGraw-Hill. Intentar embellecer nuestras ciudades y también las. 1978.

- 25. Hair J, Andreson R, Tatham R, Black W. Multivariate data analysis. 5th ed. Prentice-Hall Inc. Unites States of America; 1998.

- 26. Kaiser HF. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ Psychol Meas 1960;20(1):141-151.

- 27. Cattell RB. The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behav Res 1966 Apr;1(2):245-276.

- 28. Watkins MW. Determining parallel analysis criteria. J Mod Appl Stat Methods 2005;5(2):8.

- 29. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 1999;6(1):1-55.

- 30. Peerson A, Saunders M. Health literacy revisited: what do we mean and why does it matter? Health Promot Int 2009 Sep;24(3):285-296.

- 31. Chinn D. Critical health literacy: a review and critical analysis. Soc Sci Med 2011 Jul;73(1):60-67.

- 32. Collins PA, Abelson J, Eyles JD. Knowledge into action? understanding ideological barriers to addressing health inequalities at the local level. Health Policy 2007 Jan;80(1):158-171.

- 33. Macintyre S, McKay L, Ellaway A. Are rich people or poor people more likely to be ill? Lay perceptions, by social class and neighbourhood, of inequalities in health. Soc Sci Med 2005 Jan;60(2):313-317.

- 34. Freedman DA, Bess KD, Tucker HA, Boyd DL, Tuchman AM, Wallston KA. Public health literacy defined. Am J Prev Med 2009 May;36(5):446-451.

- 35. Kickbusch I, Wait S, Maag D. Navigating health: the role of health literacy; Alliance for health and the future, international longevity centre-UK, London. 2005 [cited 2011 October 26]. Available from: http://www emhf org/resource_images/NavigatingHealth_FINAL pdf.