A six-week-old female infant presented with nonbilious vomiting since the age of one week, occurring after each milk feed in moderate to large amounts. Stools remained normal in color and consistency. Antenatal history and scans were unremarkable. She was born at 37 weeks of gestation with a birth weight of 2.6 kg and passed meconium within 24 hours of life. On admission, she appeared emaciated and pale, with decreased muscle mass and subcutaneous fat, weighing only 2.6 kg. Physical examination revealed a soft abdomen with the liver edge palpable 1 cm below the costal margin; no other masses were noted. Systemic examination was unremarkable.

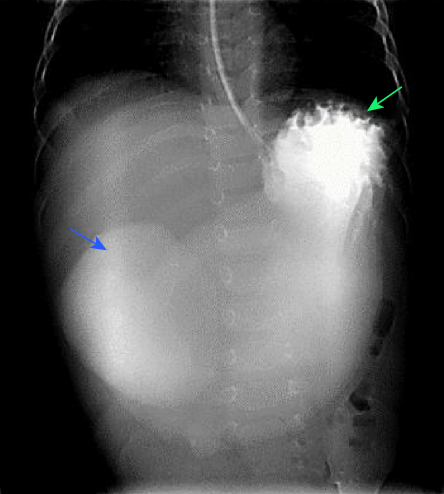

Laboratory investigations revealed hyponatremia (sodium: 118 mmol/L; (reference range: 135–145), hypokalemia (potassium: 2.6 mmol/L; reference range: 3.5–5.5 mmol/L), hypochloremia, (chloride: 77 mmol/L; reference range: 97–107 mmol/L), and metabolic alkalosis (bicarbonate: 42 mmol/L; reference range: 22–29 mmol/L). Ultrasound abdomen showed a partially distended stomach with normal pyloric width (5.5 mm) and length (12 mm). Sweat test and renin and aldosterone levels were normal. Urine sodium and urine/serum osmolality were also normal. A water-soluble upper gastrointestinal meal and follow-through demonstrated a markedly distended stomach and duodenal bulb [Figure 1]. Informed consent was obtained from the patient’s mother.

Figure 1: Anterior-posterior image of the upper gastrointestinal study shows a markedly distended stomach filled with water-soluble contrast (blue arrow). Oral contrast is seen in the first part of the duodenum (green arrow), with no contrast seen beyond this point.

Figure 1: Anterior-posterior image of the upper gastrointestinal study shows a markedly distended stomach filled with water-soluble contrast (blue arrow). Oral contrast is seen in the first part of the duodenum (green arrow), with no contrast seen beyond this point.

Questions

- What is the likely diagnosis?

- How commonly do patients with this condition present?

- How would you manage this condition?

- What is the underlying pathophysiology behind the metabolic alkalosis associated with this condition?

Answers

- Gastric outlet obstruction due to duodenal diaphragm (DD).

- Either antenatal or postnatal. DD cases can be diagnosed reliably by prenatal ultrasound, where they manifest as polyhydramnios or dilated bowel loops. Postnatally, the age of presentation and degree of obstruction are determined by the size of the DD’s aperture. Symptoms in neonates include nonbilious vomiting and abdominal distention, and in infants and toddlers, the symptoms may be delayed growth and vomiting or recurrent respiratory infections.

- Gastric decompression, fluid resuscitation, and electrolyte correction, followed by surgical correction. Endoscopic dilatation can be used in certain circumstances.

- Metabolic alkalosis results from loss of hydrogen ions, hydrogen moving into cells, exogenous administration of an alkali, or contraction of volume with a constant amount of extracellular bicarbonate.

Discussion

DD is a rare cause of intestinal obstruction. In the present case, after correcting the fluid and electrolyte imbalances, laparoscopy revealed a thick DD just above the ampulla of Vater. Consequently, duodenoduodenostomy was performed. Postoperatively, the patient recovered well and started enteral feeding in a few days.

Congenital duodenal obstruction accounts for approximately 50% of all cases of neonatal intestinal obstruction. The cause is either an intrinsic defect (such as atresia, diaphragm, or stenosis) or extrinsic compression due to annular pancreas, malrotation, or pre-duodenal portal vein.1 Congenital DD, although uncommon, may cause partial or complete obstruction. The size of the DD aperture determines the age of presentation, degree of obstruction, and radiological findings.2

The primary clinical finding at presentation in our patient was metabolic alkalosis. This condition can result from the loss of hydrogen, movement of hydrogen into cells, administration of alkali, or contraction of volume with a constant amount of extracellular bicarbonate. Hydrogen ions are mostly lost through excretion via the gastrointestinal tract or urine, which is usually accompanied by hypokalemia. Hyponatremia was also observed in our patient. During the early stages of DD, sodium wasting is common because sodium bicarbonate levels rise and exceed the renal threshold, overriding the hypovolemic mechanism, leading to excretion of both sodium and potassium bicarbonate.3 Differential diagnoses for this case included adrenal insufficiency, inborn error of metabolism, intestinal obstruction, gastroesophageal reflux disease, milk protein allergy, malrotation, and pyloric stenosis.4

DD can be diagnosed using ultrasound, prenatally (polyhydramnios or dilated bowel loops) or postnatally (annular pancreas, duplication cyst, preduodenal portal vein, or pyloric stenosis). In our patient, the ultrasound was inconclusive, but a subsequent abdominal radiography showed a ‘double bubble’ sign (gas distension in the stomach and proximal duodenum). Radiograph is typically followed by an upper gastrointestinal series, which may reveal the ‘windsock’ sign, where a duodenal membrane or web within the duodenum balloons distally. This results from contrast material being trapped behind the obstructive web, as in our patient. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are rarely required unless vascular anomalies are suspected.5

Initial management includes gastric decompression, fluid resuscitation, and electrolyte correction. The preferred surgical approach for DD is duodenostomy excision while avoiding injury to the ampulla. The survival rate is approximately 100% in term infants without serious anomalies.5 The present case was managed by laparoscopic duodenoduodenostomy. Endoscopic dilatation is possible for larger infants (≥ 5 kg) not having a fully occlusive web.6

references

- 1. Mustafawi AR, Hassan ME. Congenital duodenal obstruction in children: a decade’s experience. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2008 Apr;18(2):93-97.

- 2. Sanahuja Martínez A, Peña Aldea A, Sánchiz Soler V, Villagrasa Manzano R, Pascual Moreno I, Mora Miguel F. Tratamiento endoscópico de una membrana duodenal fenestrada mediante dilatación. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;41(6):369-370.

- 3. Davis ID, Avner ED. Fluid and electrolyte management. In: Fanaroff AA, Martin RJ. Neonatal-perinatal medicine: diseases of fetus and infant. 7th ed. Mosby; 2002. p. 619-634.

- 4. Tutay GJ, Capraro G, Spirko B, Garb J, Smithline H. Electrolyte profile of pediatric patients with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Pediatr Emerg Care 2013 Apr;29(4):465-468.

- 5. Hunter A, Johnson-Ramgeet N, Cameron BH. Case 1: progressive vomiting in a three-week-old infant. Paediatr Child Health 2008 May;13(5):387-390.

- 6. Sundin A, Huerta CT, Nguyen J, Brady AC, Hogan AR, Perez EA. Endoscopic management of a double duodenal web: a case report of a rare alimentary anomaly. Clin Med Insights Pediatr 2023;17:11795565231186895.