In 1973, Gerald Percheron, a French medical scientist, examined 50 cadaveric brain specimens in an attempt to elucidate further the anatomy and the arterial supply to the thalamus. At that time, the thalamus was recognized as an essential structure for everyday function, but was still lacking clarity. He described a variant artery, branching off from the basilar artery to the junction of the posterior communicating artery, and proposed to call it the ‘communicating basilar artery’.1 This artery was later eponymously named after him and termed the ‘artery of Percheron’. The clinical significance lies in the fact that an occlusion of this artery will lead to the phenomenon of a bilateral thalamic stroke. However, recognition of this pathology often goes unnoticed because of the vague clinical presentation, often without any focal neurological signs, potentially delaying timely thrombolytic treatment.

Case report

A 68-year-old man with type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to the emergency department with the acute onset of reduced consciousness witnessed by his wife, when he was not responsive after taking his routine afternoon nap. He had otherwise been fully conscious the morning of his presentation. He was premorbidly a high-functioning individual who remained completely independent in his activities of daily living.

There was no preceding fever or constitutional symptoms. The family denied any recent travel, and to the best of their knowledge, were unaware of any substance or illicit drug use.

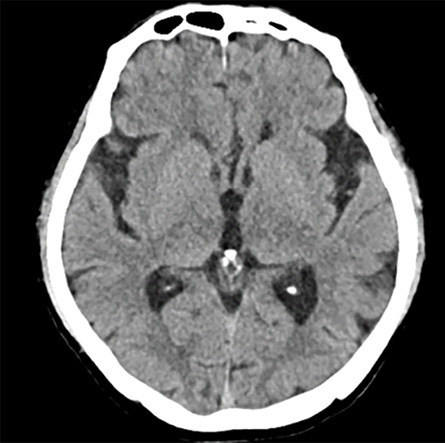

On assessment, he was predominantly drowsy, scoring 9/15 on the Glasgow Coma scale. Vital signs were otherwise unremarkable. He was breathing comfortably under ambient air. Pupils were equal bilaterally, and there were no obvious focal localizing neurological signs. His blood work and blood sugar was unremarkable. His electrocardiogram and urine toxicology screen were normal. A plain computed tomography of the brain was normal, which could not explain the reason for the acute onset of reduced drowsiness [Figure 1].

Figure 1: Plain CT brain showing no evidence of any acute infarction.

Figure 1: Plain CT brain showing no evidence of any acute infarction.

The patient was admitted to the ward with the impression of acute encephalopathy with no identifiable cause. A lumbar puncture was eventually performed on the first day of admission. (cerebrospinal fluid protein was only marginally elevated at 0.54 g/L). The cerebrospinal fluid glucose, cultures, and cytology were unremarkable.

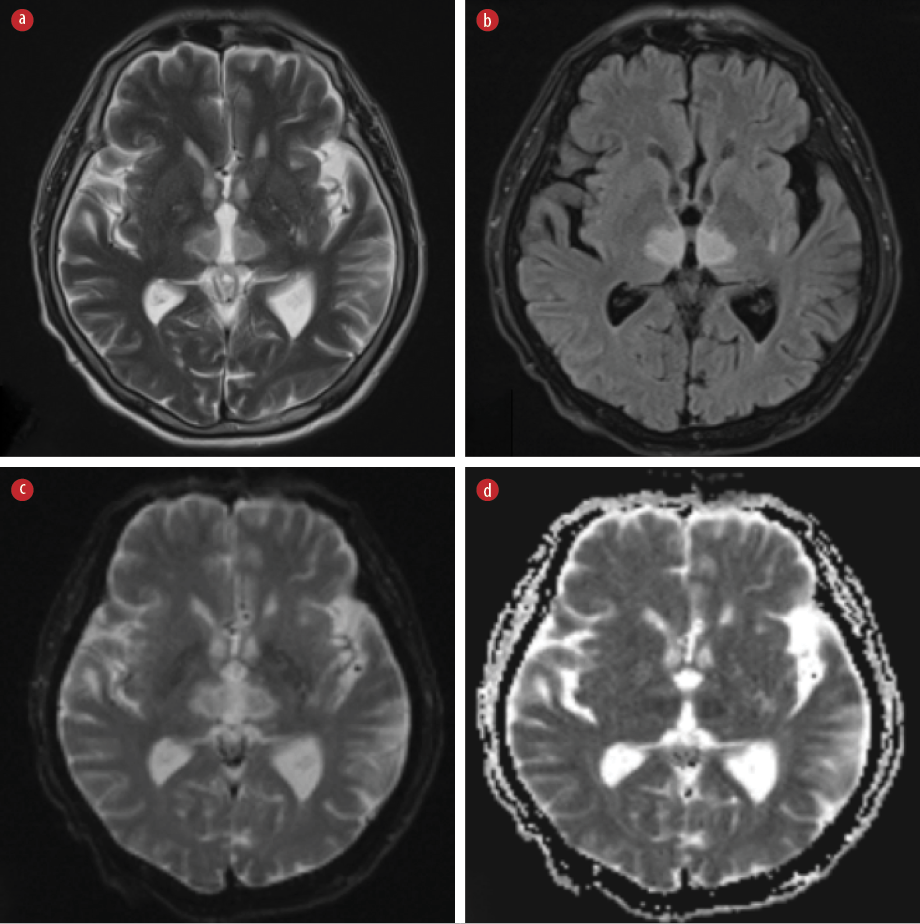

As there was no identifiable cause or diagnosis from these preliminary investigations, an magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was performed within 48 hrs of his presentation. This revealed symmetrical hyperintense lesions at bilateral thalami on axial T2-fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and on diffusion-weighted imaging with corresponding hypointensities on apparent diffusion coefficient suggestive of an acute bilateral thalamic stroke [Figure 2].

Figure 2: MRI brain images. (a) Hyperintensities at bilateral thalami on T2WI. (b) Hyperintensities at bilateral thalami on axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery. (c) Hyperintensities at bilateral thalami diffusion-weighted imaging. (d) Apparent diffusion coefficient showing hypointensities at bilateral thalami, suggesting an acute ischemic infarct.

Figure 2: MRI brain images. (a) Hyperintensities at bilateral thalami on T2WI. (b) Hyperintensities at bilateral thalami on axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery. (c) Hyperintensities at bilateral thalami diffusion-weighted imaging. (d) Apparent diffusion coefficient showing hypointensities at bilateral thalami, suggesting an acute ischemic infarct.

Correlating his acute presentation with corresponding findings on the brain MRI, the patient was diagnosed with an acute bilateral thalamic stroke. An infarction involving the artery of Percheron was suspected due to the symmetrical distribution of the infarct over the bilateral thalami. However, we were unable to perform an angiogram due to cost and financial circumstances.

The patient was started on medications for secondary stroke prevention with antiplatelets and a statin. He was eventually discharged with home care and support with fluctuations in his consciousness after a period of rehabilitation and carer training. Informed consent was obtained from the patient’s son.

Discussion

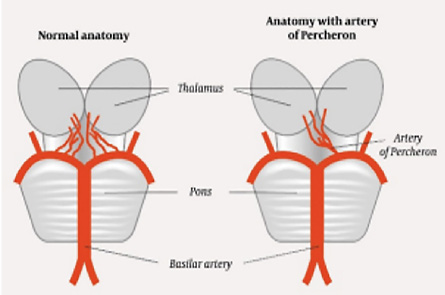

The artery of Percheron is a rare anatomical variant in which the vessel arises from the posterior cerebral artery and provides the only blood supply to the bilateral paramedian thalami and rostral midbrain.2 This variant was first described by Gerald Percheron, who extensively studied thalamic blood supply. In normal anatomy, the P1 segment of the posterior cerebral artery supplies the paramedian thalamus through the paramedian arteries on each side. Occasionally, these paramedian arteries may arise from a common trunk originating from a P1 segment on either side, and this common trunk is eponymously known as the artery of Percheron. Its estimated prevalence in the general population is approximately 7–11%.3 A bilateral paramedian thalamic infarct with or without the involvement of the rostral midbrain can result if the blood supply to the artery of Percheron is compromised.4 Thrombosis of this vessel constitutes only 0.1–2.0% of all acute ischemic stroke presentations. Classical symptoms include acute impairment in arousal with vertical gaze palsies. Unlike classical stroke syndromes, there are typically no accompanying focal neurological or pyramidal signs.5 Initial plain CT scan of the brain may appear normal. Thus, due to the ambiguity of symptoms, diagnosis can be challenging, especially in the acute setting, as illustrated in Figure 3.6

Figure 3: Schematic diagram illustrating the normal anatomical arterial supply to the bilateral thalami (left) versus the variant anatomy (right).

Figure 3: Schematic diagram illustrating the normal anatomical arterial supply to the bilateral thalami (left) versus the variant anatomy (right).

There exists a wide range of differential diagnoses for bilateral symmetrical thalamic lesions, including vascular disorders such as arterial ischemia and venous infarctions, as well as various tumors, infectious and demyelinating diseases, and metabolic-toxic alterations.7 A thorough clinical history that encompasses the acuteness of symptom onset, coupled with radiological findings, is crucial in narrowing down the differential diagnosis. More often than not, diagnosis is delayed, and patients undergo numerous invasive and investigative procedures to rule out other possible differential diagnoses.

Conclusion

This case underscores the necessity for a high clinical suspicion and recognition of this rare entity to avoid unnecessary investigations and treatment decisions that may divert clinicians away from considering an acute stroke. Patients who present within the therapeutic time frame may also benefit from thrombolytic therapy if this clinical syndrome is promptly recognized and diagnosed.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Chee Yong Chuan, Neurologist from Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia, for guidance on interpreting the MRI images.

references

- 1. Percheron G. The anatomy of the arterial supply of the human thalamus and its use for the interpretation of the thalamic vascular pathology. Z Neurol 1973 Aug;205(1):1-13.

- 2. Ranasinghe KM, Herath HM, Dissanayake D, Seneviratne M. Artery of Percheron infarction presenting as nuclear third nerve palsy and transient loss of consciousness: a case report. BMC Neurol 2020 Aug;20(1):320.

- 3. Lazzaro NA, Wright B, Castillo M, Fischbein NJ, Glastonbury CM, Hildenbrand PG, et al. Artery of Percheron infarction: imaging patterns and clinical spectrum. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010 Aug;31(7):1283-1289.

- 4. Morais J, Oliveira AA, Burmester I, Pires O. Artery of Percheron infarct: a diagnostic challenge. BMJ Case Rep 2021 Apr;14(4):e236189.

- 5. Jiménez Caballero PE. Bilateral paramedian thalamic artery infarcts: report of 10 cases. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2010;19(4):283-289.

- 6. Nadeeshani PG, Liyanage A, Rajendiran T, Indrakumar J. Acute bilateral thalamic infarctions with midbrain involvement due to artery of Percheron occlusion. J Ceylon Coll Physicians 2020;51(2):136-138.

- 7. Linn J, Hoffmann LA, Danek A, Brückmann H, Brückmann H. [Differential diagnosis of bilateral thalamic lesions]. Rofo 2007 Mar;179(3):234-245.