Small bowel obstruction (SBO) is exceptionally rare in a virgin abdomen. The main underlying causes of SBO in a virgin abdomen include congenital adhesions, internal hernia, pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, and intestinal malrotation.1 Occasionally, intestinal pseudo-obstructions can be a clinical presentation of autoimmune endocrinopathy.2 The intestinal obstruction associated with hypothyroidism can be acute, subacute, or chronic and recurrent. However, the pathophysiology of adhesive SBO in patients with hyperthyroidism is not fully understood.2 In this case report, we present a young woman with intestinal obstruction in the background of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism.

Case report

A 31-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a three-day history of abdominal pain, constipation, nausea, and vomiting. She denied any history of fever, change in urinary habits, or vaginal discharge. The rest of her systemic review was unremarkable. She was known to have Graves’ disease for which she had been prescribed carbimazole 40 mg twice daily and propranolol 40 mg once daily. Due to medication noncompliance, she was admitted with thyroid storm and symptoms of intestinal obstruction a few weeks before the current presentation. There was no past surgical history.

On examination, the patient appeared hemodynamically stable, afebrile, and showed no sign of severe systemic hyperthyroidism. Her abdomen was mildly distended and soft, with general tenderness. Bowel sounds were present, and the rest of the examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory investigations yielded the following results: normal hemoglobin level with normal inflammatory markers; serum T4: 11.0 pmol/L (reference range = 12.3–20.2 pmol/L); thyroid stimulating hormone: 0.01 mIU/L (reference range = 0.27–4.20 mIU/L); and electrolytes: within normal range.

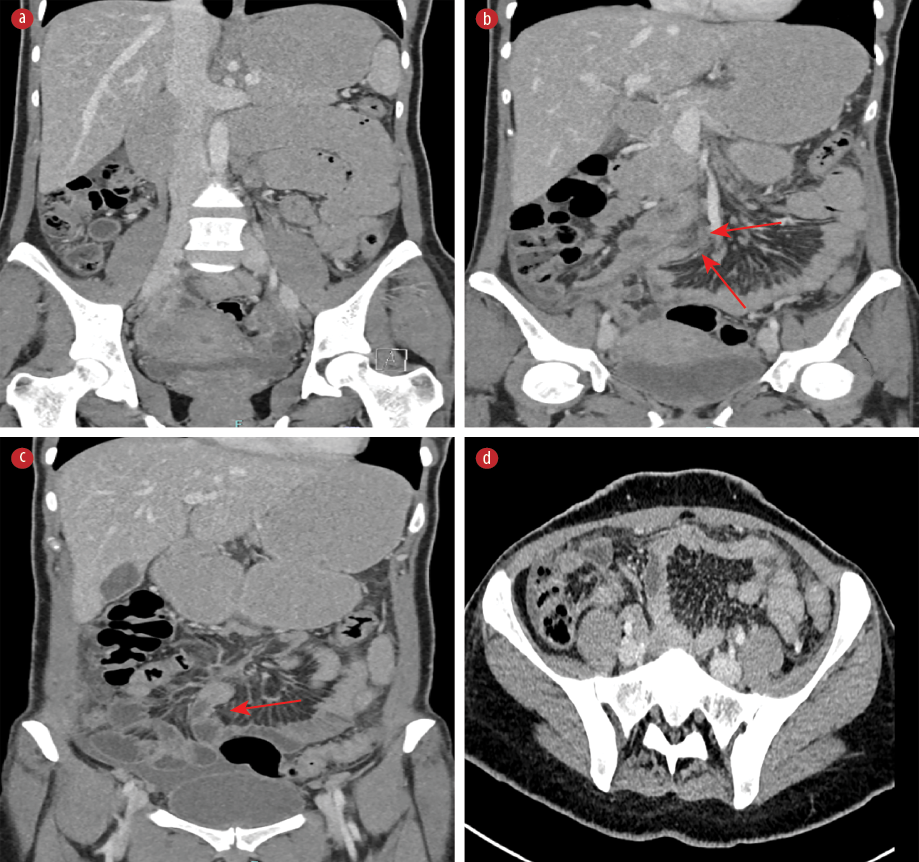

Ultrasound of the abdomen ruled out ovarian torsion, and showed a significant amount of free fluid in the right iliac fossa extending to the Morison pouch and a moderate amount of pelvic free fluid. A computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast showed distended stomach, duodenum, and proximal jejunal loops with air-fluid level and partial collapse of the distal bowel loops, omental fat stranding, moderate abdominal and pelvic ascites with thickened enhancing peritoneum, suggestive of SBO[Figure 1].

Figure 1: CT images of the abdomen and pelvis. (a) Coronal view showing multiple dilated bowel loops. (b) Coronal view showing transition point at proximal small bowel (arrows). (c) Coronal view showing another transition point (arrow). (d) Axial view showing collapsed bowel loops in the pelvis.

Figure 1: CT images of the abdomen and pelvis. (a) Coronal view showing multiple dilated bowel loops. (b) Coronal view showing transition point at proximal small bowel (arrows). (c) Coronal view showing another transition point (arrow). (d) Axial view showing collapsed bowel loops in the pelvis.

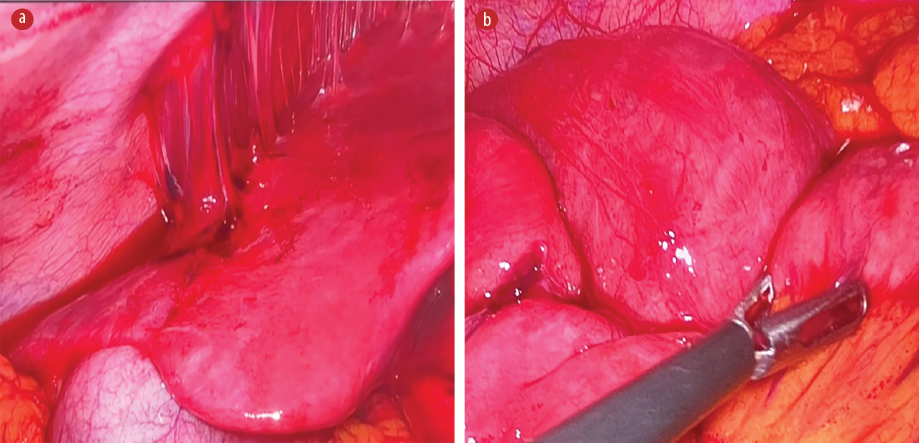

Given the absence of past abdominal surgical history and based on the clinical and radiological findings, the patient was taken to the operating theatre for diagnostic laparoscopy after initial resuscitation. Intraoperative findings included diffuse soft fibrinous adhesions between the liver and abdominal wall, dilated proximal bowel with collapsed bowel distally, and soft bands causing narrowing of the proximal jejunum [Figure 2]. Adhesiolysis was performed using a harmonic scalpel. Adhesions above the liver were also released. Upon the release of the bands, the bowel was observed to distend. The small bowel ran from the ligament of Treitz to the terminal ileum. No other pathology was detected.

Figure 2: Intraoperative findings. (a) Diffuse soft fibrinous adhesions between the liver and abdominal wall. (b) An adhesive band around the bowel with a congested dilated bowel proximal to the adhesion.

Figure 2: Intraoperative findings. (a) Diffuse soft fibrinous adhesions between the liver and abdominal wall. (b) An adhesive band around the bowel with a congested dilated bowel proximal to the adhesion.

Given the patient's medical history and intraoperative findings, the following investigations were conducted to rule out possible differential diagnoses, including immunological considerations. The results were positive for antinuclear antibodies, anti-RO52, and anti-Sjogren’s syndrome antigen A, and negative for pelvic inflammatory disease.

Postoperatively, the patient was doing well; she tolerated the oral diet and had regular bowel habits. Two days later, she was discharged from the hospital. On follow-up three weeks later, she was observed to be making a good progress on the recovery path. Consent was obtained from the patient.

Discussion

Intestinal obstructions are rarely associated with endocrinopathy, and in emergency settings, the underlying endocrinopathy is often overlooked.2–4 Endocrinopathy causing mechanical bowel obstruction similar to our patient’s presentation is even rarer. Moreover, in the context of hyperthyroidism, especially in patients who develop thyroid storm, the diagnosis could be confused as patients can present with an acute abdomen, which can mimic SBO in some cases, for which the exact cause is unknown.5

Thyroid hormones are generally metabolic hormones that have a role in gut motility and other metabolic activities.6 Digestive symptoms, such as abdominal pain, intractable vomiting, and altered bowel habits, can be the only presentation of hyperthyroidism in the absence of cardinal features of the disease.7 Such presentations can be misdiagnosed with bowel obstruction from the first encounter. In a recent study, a young patient with undiagnosed gut malrotation presented with signs and symptoms suggestive of bowel obstruction, and turned out to have thyrotoxicosis.8 The authors hypothesized that the obstruction may have resulted from increased small bowel motility due to high levels of thyroid hormones, which predispose to obstruction.8 However, in our case, the diagnosis was made after excluding all other possible diagnoses, including pelvic inflammatory disease, which can also give similar intraoperative findings of fibrinous adhesions and perihepatitis. We speculate that the patient might have developed serositis during her thyroid storm, causing fibrinous adhesions that resulted in SBO. This is why we consider this case to be rare.

Pan serositis is one of the entities associated with autoimmune endocrinopathies, including Graves’ disease.9 In 3–6% of cases, it can cause pericardial effusion in isolated ascites, and in < 4% of cases, it can cause translocation of intestinal bacteria causing peritonitis, and eventually leading to conditions including SBO, intra-abdominal complications, and pleural effusion. However, some of these occurrences tend to be underestimated due to their low clinical significance.10 To our knowledge, isolated Graves’ disease has not been reported as a cause of polyserositis, and it is usually part of the polyglandular autoimmune syndrome. However, our patient was negative for other autoimmune diseases.

Conclusion

We have presented a rare case of small bowel obstruction in a virgin abdomen, associated with uncontrolled hyperthyroidism. Bowel obstruction is a rare complication of autoimmune endocrinopathies. The diagnosis (often missed by clinicians in emergency settings) is by exclusion, especially in patients with multiple adhesions causing small bowel obstruction in the absence of other common etiologies.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

references

- 1. Sia ZK, Trautman J, Yabe TE, Wykes J. A rare case of small bowel obstruction in a patient with endosalpingiosis, fitz-hugh-curtis syndrome, and chlamydia trachomatis pelvic inflammatory disease. Case Rep Surg 2022 Oct;2022:2451428.

- 2. Bouomrani S, Lassoued N, Ben Hamad M, Regaïeg N, Belgacem N. Recurrent intestinal obstruction revealing hypothyroidism. Archives of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2018;1(1):22-25.

- 3. Hjardem E, Jørgensen LN. [Severe ileus due to hypothyroidism]. Ugeskr Laeger 2008 Sep;170(40):3144-3145.

- 4. Hernández-Ramírez DA, Castellanos-Juárez JC, Romero T, Barragan-Rincón Á, Blanco-Benavides R. [Mixedematous ileus; acute abdomen exacerbate]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 2008;73(4):231-234.

- 5. Karanikolas M, Velissaris D, Karamouzos V, Filos KS. Thyroid storm presenting as intra-abdominal sepsis with multi-organ failure requiring intensive care. Anaesth Intensive Care 2009 Nov;37(6):1005-1007.

- 6. Pokhrel B, Aiman W, Bhusal K. Thyroid storm. In: StatPearls. 2023 [cited 2023 May 2]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448095/.

- 7. Daher R, Yazbeck T, Jaoude JB, Abboud B. Consequences of dysthyroidism on the digestive tract and viscera. World J Gastroenterol 2009 Jun;15(23):2834-2838.

- 8. Bashir K, Bakhsh ZK, Gad HA, Bashir MT, Elmoheen A. An unusual case of thyroid storm masquerading as an intestinal obstruction in a patient with malrotation of the gut. Cureus 2021 Mar;13(3):e13948.

- 9. Harris E, Shanghavi S, Viner T. Polyserositis secondary to COVID-19: the diagnostic dilemma. BMJ Case Rep 2021 Sep;14(9):e243880.

- 10. Bhatia J, Kamath V, Radhika B. A rare case of hypothyroidism in a male presenting as polyserositis. APIK Journal of Internal Medicine. 2019;7(2):25-29.