Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) are the leading cause of mortality, accounting for approximately three-quarters of all deaths globally.1 Cardiovascular diseases (CVD), cancer, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases are the four major disease groups that contribute to 80% of all NCD deaths.1 Most of these deaths occur in people aged below 70 years (premature deaths). The rise of NCDs is linked to four shared modifiable risk factors: tobacco use, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and harmful use of alcohol.1 Recently, the scope of NCDs was expanded to a 5 × 5 approach with the inclusion of mental disorders as the fifth disease group and air pollution as the fifth risk factor.2

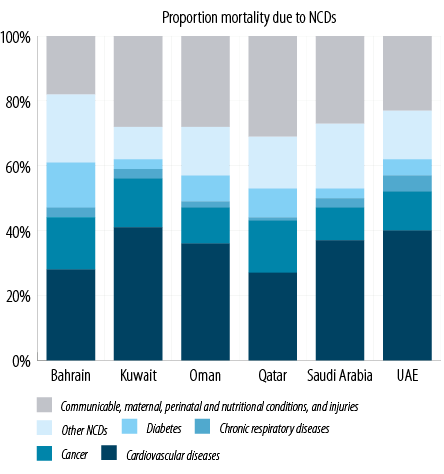

Figure 1: Noncommunicable disease burden in Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Source: World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018.4

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) consists of six Middle Eastern member countries; Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.3 NCDs account for 69%–83% of all deaths in the GCC countries.4 CVDs are the leading cause of NCD-related mortality in GCC countries [Figure 1].4 According to estimates from 2013, mental disorders contributed 2519 disability-adjusted life years/100 000 of the population in the GCC countries.5 Further, GCC countries have among the highest prevalence of diabetes in the world. As per national surveys, the prevalence of diabetes was estimated at 11.5%–15.7% in Oman (2017),6,7 14.3% in Bahrain (2007),8 14.6% in Kuwait (2015),9 16.7% in Qatar (2012),10 13.4% in Saudi Arabia (2013),11 and 11.8% in the UAE (2017).12 More recently, the 2019 International Diabetes Federation estimated the prevalence of diabetes at 16.3% in Bahrain, 22.0% in Kuwait, 8.0% in Oman, 15.5% in Qatar, 18.3% in Saudi Arabia, and 15.4% in the UAE compared with the global diabetes prevalence of 9.3%.13 These are alarming statistics as the presence of diabetes leads to a two-fold increased risk of premature death in people as it increases the risk of stroke and ischemic heart disease and leads to several other complications.14

The estimated direct and indirect costs of the five major NCDs in GCC countries were $36.2 billion in 2013; the cost of CVD and diabetes was over $11 billion.15 This cost is estimated to increase to $67.9 billion by 2022.15 The region faces a triple burden of disease contributed by NCDs (including mental health), communicable diseases, and accidental injuries. Increasing demand for health services due to population growth, including a high influx of migrant workers, longer life spans, and increased incidence of NCDs place additional pressure on healthcare systems. There is a need to make significant investments in the healthcare infrastructure and develop strategies to overcome these challenges.16

The GCC countries utilized the revenues from their natural resources to develop, modernize, and reform the national healthcare systems, and healthcare remains dependent on government funding.17 The governments’ expenditure on healthcare as a percentage of total healthcare is high compared to other high-income countries. However, the proportion of gross domestic product (GDP) contributed to healthcare by GCC countries is still not at par with developed Western countries.17 Further, the unique demographics of GCC countries (i.e., large expatriate population) have prompted countries to explore different mechanisms to minimize government health expenditure.17 The path to expanding healthcare access and ensuring equitable high-quality care for all has given many challenges to the GCC countries. Implementing universal health coverage (UHC) in the region can help prevent financial hardship, particularly for chronic conditions, and improve overall population health.18

This study aims to review the status of national healthcare systems in the GCC countries in the context of national NCD policies to highlight the challenges and identify opportunities to strengthen NCD management and control in the region.

Methods

This review is based on several data sources. PubMed was searched using search terms such as ‘Noncommunicable Diseases’, ‘NCDs’, ‘Mental health’, ‘Mental disorder’, ‘Mental illness’, ‘depression’, ‘major depressive disorder’, ‘cardiovascular’, ‘hypertension’, ‘diabetes’, ‘risk factor’, ‘tobacco’, ‘salt’, ‘physical activity’, ‘physical inactivity’, ‘healthy diet’ ‘obesity’, ‘health system’, and ‘health policy’ to identify articles relevant to NCDs in the GCC countries published in the last five years from 2014 onwards. Articles providing information on healthcare systems from the GCC countries in the context of major NCDs (i.e., CVDs, cancer, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases, and mental health disorders) as they are key drivers of NCD burden,19,20 and their risk factors were of interest for this paper. Additionally, the World Health Organization (WHO) website and Ministry of Health websites of each GCC country and, Google databases were searched to identify other relevant information.

Results

NCD prevention and risk factors

GCC countries have among the highest rates of lifestyle-related risk factors for NCDs, such as physical inactivity, high caloric diet, and obesity.13 The condition will likely worsen due to sedentary lifestyle among the aging population. There has been considerable progress in NCD preventive measures implemented by GCC countries in recent years. According to the WHO, implementing legislation (e.g.; tobacco taxes, smoking bans, salt tax, etc.) for reducing the prevalence of NCD risk factors can be a cost-effective and affordable means of curbing underlying drivers of the NCD epidemic.21 Oman joined Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, and Bahrain in implementing a tax on tobacco products, soft drinks, and energy drinks in 2019 and on sweetened beverages in 2020 to promote a healthy lifestyle along with increasing government revenues.22,23 They have also made efforts to reduce the salt content in bread produced by major national bakeries and the private sector.24,25 There is an agreement among the GCC countries for mandatory labeling of total fats, saturated fatty acids, trans-fat, and salt in all imported or locally produced food.26 Subsequently, Saudi Arabia put in effect the labeling requirement and limit on trans-fatty acids and a ban on partially hydrogenated oils.27 The UAE has introduced several preventive intervention programs for NCDs at the national level. These include a national school canteen guideline for all government schools and some private schools to promote healthy food choices, periodic screening programs for the adult population (introduced in 2014) which have been pivotal in the early detection of NCDs and associated risk factors, and integration NCDs in the national plans and strategies of Ministry of Climate Change and Environment.28–30 Oman piloted a national NCD screening program for all citizens aged ≥ 40 years in 2006, and its implementation began nationwide in 2007, which has been instrumental in the early detection of NCDs in the country.31,32 Additionally, the city of Sur in Oman has been recognized by the WHO Regional Office for Eastern Mediterranean Region (WHO/EMRO) as a “healthy city” based on the actions taken to address health determinants.33,34 Among other initiatives in the GCC countries, the Health Promotion Council in Bahrain under the National Plan for Control of Chronic Diseases and specialized clinics initiative in Saudi Arabia are noteworthy.16 It is evident that successful implementation of NCD preventive measures requires collaboration with non-health sectors. Accordingly, Oman, UAE, and Qatar have initiated the involvement of the ministries of education, municipalities, academia, sports councils, climate change, and environment in policy making with the aim of controlling NCDs through an intersectoral approach.35

Healthcare systems

The healthcare systems in the GCC countries have evolved and substantially grown over the past decade with improved quality of health services and infrastructure. Under the Gulf Plan for Control of NCDs 2011–2020 adopted by all GCC countries, Ministries of Health have developed strategic plans to ensure the provision of necessary treatment for NCDs, identify programs for the prevention of risks, integrate curative and preventive programs for NCDs, and allocate adequate budgets to combat NCDs.36 Most GCC countries have an operational multisector integrated plan/policy/strategy for NCDs and availability of local guidelines for the major NCDs at the primary care level [Table 1].38

The current healthcare systems in the GCC region are facing several challenges: inadequately trained health workforce, timely referral and follow-up of patients, and inadequate infrastructure for mental health. Analysis of critical issues in achieving health goals set-out in Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 revealed an inadequate health workforce.39 Significant challenges include insufficient numbers, skill imbalance, gender disparity, and allied access challenges. The healthcare delivery systems are dependent on a large expatriate population; and therefore, have variations in clinician competence and high turnover rates.37 Though palliative care has been included as part of national NCD action plans in most countries, there are still insufficient resources and infrastructure for expansion and delivery of palliative care in the region.40 These challenges can be overcome by strengthening primary care to deliver NCD care with a focus on proactive interventions to promote health and prevent risk factors.

Table 1: National healthcare expenditure and resources for NCD management in GCC countries.

|

Bahrain |

439.5 |

4.7% |

USD1127

(58%, 31%) |

Yes |

9.3 |

24.9 |

5.5 |

|

Kuwait |

579.2 |

5.3% |

USD 1529

(87%, 13%) |

Yes |

26.5 |

74.2 |

- |

|

Oman |

469.3 |

3.8% |

USD 588

(88%, 7%) |

Yes |

20.0 |

42.0 |

1.7 |

|

Qatar |

464.5 |

2.6% |

USD 1649

(81%, 9%) |

Yes |

24.9 |

72.6 |

2.7 |

|

Saudi Arabia |

561.8 |

5.2% |

USD 1093

(64%, 17%) |

Yes |

26.1 |

54.8 |

1.3 |

Sources: WHO. Global Health Observatory data;33 WHO. Global Health Expenditure Database.37

*Government spending and OOP expenses are the major financing sources contributing towards total health expenditure. Other sources not listed include voluntary health insurance, etc.

†Data are from the following years: Bahrain (2015), Kuwait (2015), Oman (2018), Qatar (2018), Saudi Arabia (2018), and UAE (2018).

‡Data are from the following years: Bahrain (2015), Kuwait (2018), Oman (2018), Qatar (2018), Saudi Arabia (2018), and UAE (2018).

§Data are from the following years: Bahrain (2017), Oman (2015), Qatar (2016), Saudi Arabia (2016), and UAE (2016).

GCC: Gulf Cooperation Council; GDP: gross domestic product; NCD: noncommunicable diseases; OOP: out-of-pocket expenditure; WHO: World Health Organization..

Table 2: Progress of GCC countries towards achieving the WHO NCD targets in 2020.

Mental health

A stand-alone mental health policy or plan is in place in all GCC countries. However, integration of mental health policy or plan into general public health policy is lacking in most GCC countries.41 The mental health workforce in the GCC countries remains severely under-resourced [Table 1].38

The GCC countries have prioritized mental health in their national healthcare strategies. Kuwait identified mental health as one of six strategic priorities, and as part of this agenda mental health services are planned to be integrated into primary healthcare, and community and home-based services are being developed.3 Oman has planned to scale-up mental health services by increasing the number of available beds, providing training for primary care workers, and implementing a school health program.3 Qatar recently developed a National Mental Health Strategy, which focuses on system-wide changes to reduce stigma, improve treatment-seeking, increase the availability of resources, scale up the workforce, provide services in a variety of locations, and develop standards and guidelines.3 To address mental health issues and decrease the associated stigma, the UAE developed a national policy to promote mental health in 2017. The policy highlighted promotion of mental health awareness, integration of mental health in primary healthcare, multisectoral collaboration for policy implementation, prevention of mental disorders, and capacity building of healthcare providers and psychologists as the key strategic objectives.42 Bahrain and Saudi Arabia have also emphasized mental health as a national priority, and service development is underway in these counties as well.3

Health financing for NCDs

The government expenditure on healthcare in the GCC countries (3.8% of GDP) is lower compared with other high-income countries (10% of GDP), despite comparable income levels [Table 1].43 There is considerable variability in healthcare financing in terms of out-of-pocket (OOP) spending and the reliance on the private sector among the GCC countries.43 The healthcare system in Oman is predominantly financed by the government, with the private sector covering OOP spending accounting for approximately 20% of the total health expenditure.44 In Saudi Arabia, health services are provided mostly by the government, and OOP payments decreased following the implementation of the Compulsory Employment-Based Health Insurance system.17 UAE implemented a new financing model for its citizens and resident expatriates in parallel with the free government health services for citizens through an innovative system of mandatory health insurance.45 Under the new model, employers or sponsors are required to provide health insurance for all private- sector employees and their dependents in the UAE.45 The compulsory health insurance plan for the private-sector was implemented across the emirate of Abu Dhabi in 2008 (Thiqa), Dubai in 2015 (Saada), and will soon be implemented across all emirates.45 Hallmarks of the new system included a clear and transparent reimbursement process, affordable access for all residents, and reliable funding for quality health care.30 In the UAE, health system reforms have led towards mandatory private health insurance for all citizens, development of private sector, and sequestration of planning/regulatory responsibilities from provider function.30 Overall, the healthcare delivery system in UAE is dominated by the private sector, as evident by private pharmacies, corporate hospitals, and private healthcare insurers.30 However, heterogeneous implementation of the health reforms across the country highlights variations in access, affordability, and quality.30

Several GCC countries are also looking to reform their private healthcare system to ensure equitable and efficient healthcare services.17 As mandated by the WHO, GCC countries have adopted frameworks for advancing UHC. Some measures include mandatory national social health insurance and direct financial protection for citizens and expatriates. However, the diversity in healthcare delivery and the emerging healthcare challenges have hampered the efforts toward achieving UHC in the region.16

NCD surveillance and research

An important indicator of national progress on the United Nations framework for NCDs is the area of surveillance, monitoring, and evaluation.46 The progress in this area is measured by the presence of a functioning system for generating reliable cause-specific mortality data on a routine basis, a comprehensive periodic health examination survey, and an operational population-based cancer registry. In most GCC countries, a population-based cancer registry is operational; however, accurate reporting of NCD disease burden and a surveillance mechanism such as the WHO STEPwise approach to surveillance (STEPWISE) survey is not conducted in most countries periodically as mandated.38,47 Several programs have been initiated to overcome this gap. In Qatar, an e-health program has been initiated to upgrade healthcare services.48 Saudi Arabia has begun digitalizing its hospitals and patients’ medical records through Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society.16 The UAE plans to integrate patients’ electronic medical records (eMR) with public hospitals and clinics in Abu Dhabi through the “Malaffi” health information exchange, and across Dubai and the Northern Emirates through the Wareed health information system.49 Finally, Oman’s Ministry of Health has developed an e-health service by linking identity cards to hospital registration.50

There is a conspicuous lack of Arab populations in high-quality prospective cohort studies that understand environmental and genetic factors contributing to the diseases. Hence, there is a need for collaborative research in the region to understand the importance of novel and established risk factors of NCDs. The contribution of the region to the medical literature is also far below what should be achievable, given both the human and financial resources available in some countries. The UAE Healthy Future study is a large-scale, population-based study initiated in 2014 and plans to recruit approximately 20 000 healthy participants. This is the first large scale cohort study for evaluating the risk factors (proximal, distal, and genetic) for obesity, diabetes, and CVD in a GCC population.51

Discussion

With improvements in healthcare services and recent industrialization, GCC countries are experiencing increased life expectancies, significant population growth, and a more sedentary lifestyle. There is a high prevalence of lifestyle-related risk factors for NCDs, particularly among women.15 However, the healthcare systems in these countries may not be adequately equipped to tackle this rising NCD burden effectively, as evident by the high prevalence of NCDs, premature mortality due to the NCDs, and the associated complications, for example, end-stage renal disease.4,52 The WHO has proposed a roadmap for the prevention and control of NCDs, which includes nine voluntary global targets including a 25% relative reduction in premature mortality from NCDs by 2025.53 The WHO Eastern Mediterranean regional framework provides strategic interventions to achieve these targets in governance, prevention and reduction of risk factors, surveillance, monitoring and evaluation, and healthcare.46 There is considerable ground still to be covered by the GCC countries towards achieving the NCD targets by 2030 [Table 2].54

Management of NCDs needs strengthening and capacity building of primary care, and a paradigm shift towards holistic and preventive care. Public health intervention programs against NCDs and their risk factors began in the 1970s in the USA and Europe and generated a vast amount of evidence on the cost-effectiveness and generalizability of these programs.55 These interventions can help inform policies in other healthcare systems that need a stronger focus on promoting a healthy lifestyle, such as educational programs to aid lifestyle modifications in the population. GCC countries have introduced NCD preventive measures to varying degrees through legislation (reduction of salt in bakeries, guidance on use of trans-fats, and tobacco control) as well as health education and promotion measures. However, most of these preventive measures require the cooperation of non-health sectors which do not necessarily prioritize these measures. Therefore, addressing NCDs demands a whole-of-government, whole-of-society, and health-in-all policies approach.56

Efforts are also needed to integrate NCD prevention and screening programs and diagnostic services into healthcare plans. In many GCC countries, health systems are not aligned at the organizational level, and health departments overseeing NCD programs have varied focus on hospital care, primary care, or private care. Therefore, the integration of NCD prevention programs with screening programs must also be at the level of organizational alignment to ensure continuity of care for patients. There remains a shortage of adequately trained physicians/nurses in the GCC countries, particularly local professionals. Most high-income member countries of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, such as the UK are also confronted with a shortage of healthcare personnel and are unable to keep pace with the increasing healthcare demands of the growing population burdened by aging demographics.57 Some common solutions proposed to build the capacity of trained health workforce include implementing training and mentoring programs, improving overall working conditions, and incentivizing nursing and other healthcare jobs for the domestic population.57 A lack of basic and clinical research in this population remains a huge gap that impedes the development of effective treatment strategies and effective implementation of NCD programs due to a dearth of risk factor surveillance and reliable mortality data.

Mental health is fundamental to health and is defined as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”.58 The WHO comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2020 emphasizes integration of mental health services in community-based settings and it calls for an expansion of services to promote greater efficiency in the use of resources.58 Integration of mental health in primary care has demonstrated an increased likelihood of positive outcomes for mental and physical health problems and healthcare cost-benefits when implemented across several countries with vastly different socioeconomic conditions and healthcare resources.59 With a quarter of the population of GCC countries comprised of adolescents, which is much higher than in other high-income countries, mental health is a growing concern in the region.60 Despite this, only 80% of the GCC countries have a plan or strategy for child or adolescent mental health.41

There are some limitations to this study. This article did not follow a systematic search approach as it was observed that most of the current national NCD policy and strategy information was published as grey literature along with peer-reviewed scientific articles. Though we made efforts to include records from the WHO website and the government Ministry of Health websites, the records obtained may not be exhaustive. Studies published in local languages were not included - as a result, some regional/national NCD initiatives may not have been covered. Finally, as some of the initiatives were started recently, the data on their impact and effectiveness is not available.

This paper presents an overview of the NCD preparedness of healthcare systems in GCC countries. Further studies need to be undertaken for detailed and systematic examination of each aspect of NCD provisions in these countries to inform practical interventions for improving NCD care.

Conclusion

The GCC countries are grappling with a burgeoning healthcare challenge due to the NCD epidemic, which necessitates adapting and strengthening their healthcare systems. Some of the recommendations to reduce the NCD burden in the region include strengthening primary care to deliver NCD care continuum with a focus on holistic and preventive care, increasing the capacity of adequately trained health workforce through improved training and education, addressing the lack of research among the local populations to develop effective treatment strategies, integrating mental health into general public health policy, and establishing reliable NCD surveillance and monitoring programs.

Disclosure

Dr. Ali has received honoraria from Pfizer Upjohn. Dr. Saeed and Dr. Arifeen are employees of Pfizer Upjohn. The authors declared no other conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Tanaya Bharatan, Lead, Medical Center of Excellence, Pfizer Upjohn, and Kaveri Sidhu, Senior Scientific Communications Specialist, Pfizer Upjohn for providing medical writing support funded by Pfizer Upjohn.

references

- 1. World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases. [cited 2020 February]. Available from: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

- 2. Stein DJ, Benjet C, Gureje O, Lund C, Scott KM, Poznyak V, et al. Integrating mental health with other non-communicable diseases. BMJ 2019 Jan;364:l295.

- 3. Hickey JE, Pryjmachuk S, Waterman H. Mental illness research in the Gulf Cooperation Council: a scoping review. Health Res Policy Syst 2016 Aug;14(1):59.

- 4. Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2018. [cited 2020 February]. Available from: https://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd-profiles-2018/en/.

- 5. Charara R, Forouzanfar M, Naghavi M, Moradi-Lakeh M, Afshin A, Vos T, et al. The Burden of Mental Disorders in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 1990-2013. PLoS One 2017 Jan;12(1):e0169575.

- 6. Sultanate of Oman STEPS Survey 2017. Fact Sheet Omani and Non-Omani 18+. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/steps/Oman_STEPS_2017_Fact_Sheet.pdf?ua=1.

- 7. Ministry of Health Sultanate of Oman STEPS Survey 2017. Centre of Studies & Research. Fact Sheet Omani and Non-Omani 18+. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://mohcsr.gov.om/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Fact-Sheet-1-Omani-Non-Omani-18.pdf.

- 8. Ministry of Health Kingdom of Bahrain. National non-communicable diseases risk factor survey 2007. Manama: Ministry of Health Kingdom of Bahrain. 2009. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.bh/Content/Files/Publications/X_2812013135226.pdf.

- 9. Survey of Risk Factors for Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases. 2015. State of Kuwait: Eastern Mediterranean Approach for Control of Non-Communicable Diseases. 2015. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/steps/Kuwait_2014_STEPS_Report.pdf.

- 10. Haj Bakri A, Al-Thani A. Chronic Disease Risk Factor Surveillance: Qatar STEPS Report 2012. The Supreme Council of Health. Qatar. 2013. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/steps/Qatar_2012_STEPwise_Report.pdf.

- 11. Ministry of Health Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Health Interview Survey Results. Riyadh. 2013. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: http://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/Projects/KSA/Saudi-Health-Interview-Survey-Results.pdf.

- 12. Ministry of Health & Prevention United Arab Emirates. Non-communicable Disease Risk Factor Survey (STEPS). Data Book for UAE 2017-2018. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://www.mohap.gov.ae/Files/MOH_OpenData/1574/STEPS_DataBook_UAE_25%20NOV%202019.pdf.

- 13. Diabetes Atlas ID. 9th Edition. 2019. [cited 2020 February]. Available from: https://www.diabetesatlas.org/en/.

- 14. Almdal T, Scharling H, Jensen JS, Vestergaard H. The independent effect of type 2 diabetes mellitus on ischemic heart disease, stroke, and death: a population-based study of 13,000 men and women with 20 years of follow-up. Arch Intern Med 2004 Jul;164(13):1422-1426.

- 15. Alshaikh MK, Filippidis FT, Al-Omar HA, Rawaf S, Majeed A, Salmasi AM. The ticking time bomb in lifestyle-related diseases among women in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries; review of systematic reviews. BMC Public Health 2017 Jun;17(1):536.

- 16. Khoja T, Rawaf S, Qidwai W, Rawaf D, Nanji K, Hamad A. Health Care in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: A Review of Challenges and Opportunities. Cureus 2017 Aug;9(8):e1586.

- 17. Alkhamis A, Hassan A, Cosgrove P. Financing healthcare in Gulf Cooperation Council countries: a focus on Saudi Arabia. Int J Health Plann Manage 2014 Jan-Mar;29(1):e64-e82.

- 18. Alshamsan R, Leslie H, Majeed A, Kruk M. Financial hardship on the path to Universal Health Coverage in the Gulf States. Health Policy 2017 Mar;121(3):315-320.

- 19. NCD Countdown 2030 collaborators. NCD Countdown 2030: worldwide trends in non-communicable disease mortality and progress towards Sustainable Development Goal target 3.4. Lancet 2018 Sep;392(10152):1072-1088.

- 20. Pryor L, Da Silva MA, Melchior M. Mental health and global strategies to reduce NCDs and premature mortality. Lancet Public Health 2017 Aug;2(8):e350-e351.

- 21. Tackling NCDs. “Best buys” and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. World Health Organization. [cited 2020 February]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259232.

- 22. More tax in the Middle East: Oman joins Saudi and Qatar in introducing tax on energy and soft drinks. 2019. [cited 2020 February]. Available from: https://www.foodnavigator-asia.com/Article/2019/06/05/More-tax-in-the-Middle-East-Oman-joins-Saudi-and-Qatar-in-introducing-tax-on-energy-and-soft-drinks.

- 23. Oman’s new ‘sin tax’ to come into effect in June. The National. 2019. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://www.thenational.ae/business/economy/oman-s-new-sin-tax-to-come-into-effect-in-june-1.836999.

- 24. Alhamad N, Almalt E, Alamir N, Subhakaran M. An overview of salt intake reduction efforts in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2015 Jun;5(3):172-177.

- 25. Kuwaitis lower blood pressure by reducing salt in bread. World Health Organization. 2014. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://www.who.int/features/2014/kuwait-blood-pressure/en/.

- 26. Kamel S, Trans-Fats Declaration AO. Awareness and Consumption in Saudi Arabia. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci 2018;6(3) .

- 27. Trans Fat Free by. 2023. Case Studies in Trans Fat Elimination. 2019; [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://ncdalliance.org/sites/default/files/resource_files/NCDA%20Trans%20Fats%20Acids_Case%20Studies_Web_single%20pages_FINAL.pdf.

- 28. Guidelines and requirements for food and nutrition in schools in Dubai. 2017. [cited 2020 May]. Available from: http://www.foodsafe.ae/pic/requirements/School_Canteen_Guidelines_Eng_v1.pdf.

- 29. Fadhil I, Belaila B, Razzak H. National accountability and response for noncommunicable diseases in the United Arab Emirates. Int J Noncommun Dis 2019;4(1):4-9 .

- 30. Koornneef E, Robben P, Blair I. Progress and outcomes of health systems reform in the United Arab Emirates: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2017 Sep;17(1):672.

- 31. Ministry of Health Sultanate of Oman. Operational and Management Guidelines for the National Noncommunicable Diseases Screening Program. 2010. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.om/documents/272928/1314763/Operational+and+management+guidelines+for+the_National_NCD_screening_program.pdf/d50b3a2d-5861-481f-9b78-fc499152f13d.

- 32. MOH Launches National Policy & Multisectoral Plan on NCDs. 2018. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.om/en/-/---669.

- 33. Regional Healthy City Network. 2010. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/omn/programmes/health-promotion-and-community-based-initiatives.html.

- 34. Elfeky S, El-Adawy M, Rashidian A, Mandil A, Al-Mandhari A. Healthy Cities Programme in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: concurrent progress and future prospects. East Mediterr Health J 2019 Oct;25(7):445-446.

- 35. Samara A, Andersen PT, Aro AR. Health Promotion and Obesity in the Arab Gulf States: Challenges and Good Practices. J Obes 2019 Jun;2019:4756260.

- 36. Gulf Plan for Control of NCDs 2011–2020. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: http://ghc.sa/en-us/Pages/noncommunicablediseaseprogram.aspx.

- 37. Brownie SM, Hunter LH, Aqtash S, Day GE. Establishing Policy Foundations and Regulatory Systems to Enhance Nursing Practice in the United Arab Emirates. Policy Polit Nurs Pract 2015 Feb-May;16(1-2):38-50.

- 38. Global Health Observatory. [cited 2020 February]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.A858?lang=en.

- 39. Albejaidi F, Nair KS. Building the health workforce: Saudi Arabia’s challenges in achieving Vision 2030. Int J Health Plann Manage 2019 Oct;34(4):e1405-e1416.

- 40. Fadhil I, Lyons G, Payne S. Barriers to, and opportunities for, palliative care development in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Lancet Oncol 2017 Mar;18(3):e176-e184.

- 41. Mental health atlas 2017. Resources for mental health in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: http://applications.emro.who.int/docs/EMROPUB_2019_2644_en.pdf?ua=1&ua=1.

- 42. Mental Health: Published Work on Mental Health in the United Arab Emirates – 1992 - 2019. 2019. [cited 2020 May]. Available from: https://u.ae/-/media/Information-and-services/Health/mental-health.ashx?la=en.

- 43. Global health expenditure database. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/nha/database/country_profile/Index/en.

- 44. Ministry of Health Sultanate of Oman. Health Vision 2050. 2014. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.om/documents/16506/119833/Health+Vision+2050/7b6f40f3-8f93-4397-9fde-34e04026b829.

- 45. Health insurance. 2019. [cited 2020 May]. Available from: https://u.ae/en/information-and-services/health-and-fitness/health-insurance.

- 46. Framework for action to implement the United Nations Political Declaration on Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), including indicators to assess country progress by 2030. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://applications.emro.who.int/docs/EMRPUB-NCD-146-2019-EN.pdf?ua=1&ua=1&ua=1&ua=1.

- 47. Country Reports ST. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/steps/reports/en/.

- 48. Qatar National E-Health & Data Program (QNeDP). [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://www.moph.gov.qa/english/strategies/Supporting-Strategies-and-Frameworks/NationalEHealthAndDataManagementStrategy/Pages/default.aspx.

- 49. The UAE healthcare sector.: An update. U.S-UAE. Business council report. 2018. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://usuaebusiness.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Healthcare-Report-Final-January-2018-Update-1.pdf.

- 50. Oman Ministry of Health. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://omanportal.gov.om/wps/wcm/connect/en/site/home/gov/gov1/gov5governmentorganizations/moh/healthid.

- 51. New York University Abu Dhabi. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://nyuad.nyu.edu/en/research/centers-labs-and-projects/public-health-research-center/uae-healthy-future-study.html.

- 52. AlSahow A, AlRukhaimi M, Al Wakeel J, Al-Ghamdi SM, AlGhareeb S, AlAli F, et al; GCC-DOPPS 5 Study Group. Demographics and key clinical characteristics of hemodialysis patients from the Gulf Cooperation Council countries enrolled in the dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study phase 5 (2012-2015). Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 2016 Nov;27(6)(Suppl 1):S12-S23.

- 53. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013-2020. 2013. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/94384/9789241506236_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- 54. Noncommunicable Diseases Progress Monitor. 2020. [cited 2020 February]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/ncd-progress-monitor-2020.

- 55. Nissinen A, Berrios X, Puska P. Community-based noncommunicable disease interventions: lessons from developed countries for developing ones. Bull World Health Organ 2001;79(10):963-970.

- 56. WHO Independent High-level Commission on NCDs Report of Working Group 1. 2019. [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://www.who.int/ncds/governance/high-level-commission/HLC2-WG1-report.pdf?ua=1.

- 57. Kumar N, Mustafa S, James C, Barman M. The economics of healthcare personnel shortage on the healthcare delivery services in the United Kingdom versus the Gulf Cooperation Council. Saudi Journal of Health Sciences. 2019;8(3):127-132 .

- 58. Mental health action plan 2013–2020. [cited 2020 February]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/89966/9789241506021_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- 59. World Health Organization. WONCA. Integrating mental health into primary care: A global perspective. 2008. [cited 2020 August 5]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/Integratingmhintoprimarycare2008_lastversion.pdf?ua.

- 60. Al Makadma AS. Adolescent health and health care in the Arab Gulf countries: Today’s needs and tomorrow’s challenges. Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med 2017 Mar;4(1):1-8.