Increased awareness of cosmetic surgery and body image concerns has made liposuction a popular surgical operation. Liposuction, initiated in the 1970s in Italy, is defined as the removal of fat from deposits beneath the skin using a cannula with the assistance of a powerful vacuum. It may be performed in hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, or physician offices. The safety of the technique relates not only to the amount of tissue removed, but also to the choice of anesthetic and the patient’s health condition. There are four types of liposuction techniques and their main difference is the amount of infiltration done into the tissues and the resultant blood loss as a percentage of aspirated fluid. Liposuction is considered a high-risk office-based procedure.1–3 Reported perioperative deaths have been attributed to anesthetic complications, abdominal viscous perforation, fat embolism, hemorrhage, and unknown causes.3

The tumescent technique, developed by Dr. Klein, uses a special instrument to efficiently anesthetize the subcutaneous space with a very dilute solution of lidocaine/epinephrine.4

The tumescent technique is nowadays the most common of all liposuction techniques. Large volumes of dilute local anesthetic (wetting solution) are injected into the fat to facilitate anesthesia and decrease blood loss. The concentration of lidocaine injected varies and may reach large toxic doses (35–55 mg/kg) in patients desiring extensive liposuction, raising concerns regarding local anesthetic toxicity especially after the reports of adverse outcomes.4–7

Case report

A 33-year-old previously healthy woman weighing 70 kg was brought to the emergency department (ED) by Emergency Medical Services (EMS) in cardiac arrest. The patient was undergoing liposuction of her thighs in a physician’s clinic with no intraoperative complications a few minutes before the event. The surgeon reported harvesting 1.5 L of fat from the patient’s thigh and mid-back during the procedure, which lasted 45 minutes.

A few minutes following the procedure, the surgeon noticed that the patient was becoming more somnolent. Her vital signs were stable, including a blood pressure of 170/90 mmHg. The doctor suspected a possible clinical manifestation of hypoglycemia and subsequently administered oral dextrose solution without any improvement.

Two hours after the procedure, the patient started feeling dizzy with a rapid decline of her mental status leading to tonic-clonic seizure followed by a complete loss of consciousness. EMS arrived on the scene after five to 10 minutes. EMS personnel reported the patient was gasping, cyanotic, and drooling. During transport to the ED, she had a cardiopulmonary arrest, so the EMS team immediately initiated resuscitation using Basic Life Support guidelines.

Upon arrival to the ED, the cardiac monitor showed asystole, so the patient was intubated and resuscitation resumed using the advanced cardiac life support algorithm. Return of spontaneous circulation was achieved after 12 minutes of resuscitation in the ED (22 minutes post-arrest).

The plastic surgeon who performed the procedure was asked for details about the procedure technique and the anesthesia modality. He reported using the power-assisted liposuction technique in his private clinic. As for anesthesia, he reported the use of five vials of 50 mL lidocaine 2% (20 mg/mL) subcutaneously during the operation; making the total dose of lidocaine equal to 5000 mg. He also pointed to prior use of the same procedure and anesthesia three months earlier while performing an uncomplicated abdominal liposuction on the same patient.

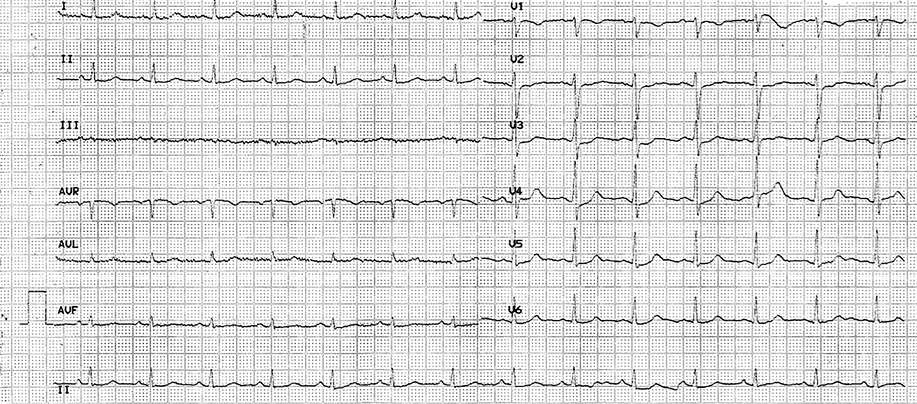

Following the return of spontaneous circulation, electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm, no QT prolongation with a corrected QT interval (QTc) of 466 ms and a normal QRS interval of 100 ms with no ST- or T-wave abnormalities [Figure 1].

Figure 1: Electrocardiogram following return of spontaneous circulation.

Neurological examination revealed no response to verbal or painful stimuli (Glasgow Coma Scale of 3T), pupils equal in size bilaterally and reactive to light, preserved corneal and oculocephalic reflexes, and a downward Babinski reflex bilaterally.

Arterial blood gas analysis on mechanical ventilation on 100% fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) showed a pH of 7.34, a CO2 pressure of 39.9 mmHg, an O2 pressure of 131 mmHg, and a bicarbonate concentration of 20.8 mmol/L.

Laboratory workup included a complete blood count, and measurement of serum electrolytes, lactate, cardiac and liver enzyme levels. The results were the following: white blood cell count 9.8 × 109/L with 41% polymorphonuclear cells; a hemoglobin level 10.4 g/dL; platelet count 336 × 106/L; troponin 0.003 ng/mL; sodium concentration 144 mmol/L; potassium 3.5 mmol/L; chloride 99 mmol/L; bicarbonate 16 mmol/L; glucose 346 mg/dL; blood urea nitrogen 13 mg/dL; creatinine 1.0 mg/dL; aspartate aminotransferase 225 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase 238 IU/L; γ-glutamyl transpeptidase 12 IU/L; alkaline phosphatase 55 IU/L; and lactate 17.55 mmol/L. Her serum lidocaine level upon presentation to the ED was 5.30 µg/mL (therapeutic range = 1.50–5.00 µg/mL).

Imaging included a computerized tomography (CT) scan of the brain without contrast material as well as CT angiography of the chest to rule out intracranial bleed and massive pulmonary embolism, respectively, which could be a reason for the patient’s arrest. Positive findings included bilateral consolidations consistent with aspiration pneumonitis without any signs of intracranial bleeding, pulmonary embolism, or aortic dissection. The patient was started on antibiotic therapy.

The patient developed generalized myoclonic jerks that were attributed to possible anoxic brain injury following her cardiac arrest so she was started on valproic acid.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was done three days later and showed signs of severe hypoxic-ischemic brain injury, which was confirmed by electroencephalogram (EEG) (electrocerebral silence on EEG).

The patient’s hospital stay was complicated by an increase in brain edema and pressure, electrolytes disturbances, multiple nosocomial infections with end-organ damage leading to the patient’s death secondary to septic shock two months later.

Discussion

Lidocaine is a synthetic aminoethylamide, which is a widely used local anesthetic agent, usually well tolerated and considered much less cardiotoxic than other local anesthetics. Other uses include acute management of intractable ventricular arrhythmias. Lidocaine stabilizes the neuronal membrane by binding to and inhibiting voltage-gated sodium channels, thereby inhibiting the ionic fluxes required for the initiation and conduction of impulses and effecting local anesthesia. The onset of lidocaine action ranges from 45 to 90 seconds. The volume of its distribution is equal to 1.5±0.6 L/kg and is alterable by many patient factors (e.g., decreased congestive heart and liver failure). This drug crosses the blood-brain barrier with its major form (60–80%) in the plasma bound to alpha-1-acid glycoprotein. It has a 90% hepatic metabolism forming monoethylglycinexylidide and glycinexylidide, which may accumulate and cause central nervous system toxicity. Its half-life ranges between 1.5 and 2 hours. It is excreted in the urine (< 10% as unchanged drug and around 90% as metabolites). Maximal local cutaneous infiltration injectable dose is 4.5 mg/kg/dose not to exceed 300 mg.

Signs and symptoms of lidocaine toxicity tend to follow a progression of central nervous system excitement. The patient may initially experience perioral numbness, facial tingling, pressured or slurred speech, metallic taste, auditory changes, and hallucinations, which may also be accompanied by hypertension and tachycardia. As the condition evolves, seizures or central nervous system depression may develop, and severe cases may experience cardiac failure and even arrest.8

The American Academy of Dermatology has published guidelines for liposuction indicating a maximum safe dose of lidocaine of 55 mg/kg.9 However, this remains an area of significant controversy since the maximum recommended dose of local anesthetics is a multifactorial concept.7 For an overdose to occur, the drug must gain access to the affected organs or tissues in the concentration needed. Patients predisposing factors include age (under six and over 65 years), lean body weight (disproportionate relationship with risk of toxicity), presence of pathology (e.g., liver, pulmonary, and cardiovascular diseases), genetics (e.g., atypical pseudocholinesterase for ester-type local anesthetics), mental attitude (anxiety decreases seizure threshold), and pregnancy (slightly increased risk in pregnant women). Drug predisposing factors include vasoactivity of drug (higher lipid solubility and protein binding decrease risk of toxicity while vasodilation increases its risk), route of administration (intravascular injection increases toxicity risk), rate of infusion, vascularity of administration site (increases the toxicity), and the presence of vasoconstrictor (decreases the risk).10,11

Some experts state that 35 mg/kg is a more reasonable threshold of toxicity noting that the hepatic metabolism of lidocaine using CYP3A4 is saturable and once saturation occurs, absorption exceeds elimination and plasma lidocaine concentrations increase precipitously.3

One study addressed the question of safe dosing limits for tumescent lidocaine infiltration with and without subsequent liposuction.12 Preliminary estimates for maximum safe dosages of tumescent lidocaine were 28 mg/kg without liposuction and 45 mg/kg with liposuction. As a result of delayed systemic absorption, these dosages yield serum lidocaine concentrations below levels associated with mild toxicity and pose an insignificant risk of harm to patients.

Some studies reported that large doses of lidocaine (e.g., 35 mg/kg) are safe and prudent for tumescent infiltration.13,14

Absorption of local anesthetic from the subcutaneous tissue is variable; thus, the timing for lidocaine toxicity symptom onset is unpredictable.15,16 Although blood lidocaine levels typically peak 12 to 16 hours after the initial injection of infiltrate solution, peaks may occur within two hours of injection, particularly if tumescent lidocaine without epinephrine is used (e.g., for endovenous laser therapy). Thus, close postoperative monitoring in the office-based recovery area is necessary, and lipid emulsion should be immediately available for prompt treatment.

The patient described in this case report, weighing 70 kg, received a lidocaine dose of 5000 mg, equivalent to 71 mg/kg. This dosage exceeds the previously described toxic doses, and therefore, warrants the development of subsequent local anesthetic systemic toxicity.

The differential diagnosis of such case would also include other more frequent postoperative complications following liposuction including massive pulmonary thromboembolism, fat embolism syndrome, hypovolemic hypotension, and vasovagal syncope.

In 2011, a case of a patient successfully resuscitated with lipid emulsion therapy after prolonged and intractable lidocaine toxicity was reported17 demonstrating the need to consider lipid emulsion therapy in the advanced cardiac life support algorithm for lidocaine toxicity.

In our case, instructions were given to administer 20% lipid emulsion in case of cardiovascular deterioration including ventricular arrhythmias or cardiac arrest during the 24 hours following the admission.

Conclusion

We describe a case of cardiac arrest secondary to the use of a toxic dose of lidocaine during a liposuction procedure in a physician’s clinic. This case raises a concern about the safety of performing such procedures in private clinics and is compatible with the previously discussed lidocaine toxic dose threshold.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

references

- 1. Hausman LM, Rosenblatt M. Office-based Anesthesia. In: clinical Anesthesia, 7th ed, Barash PG, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia 2013. p. 860.

- 2. Coldiron BM, Healy C, Bene NI. Office surgery incidents: what seven years of Florida data show us. Dermatol Surg 2008 Mar;34(3):285-291, discussion 291-292.

- 3. Grazer FM, de Jong RH. Fatal outcomes from liposuction: census survey of cosmetic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000 Jan;105(1):436-446, discussion 447-448.

- 4. Lehnhardt M, Homann HH, Daigeler A, Hauser J, Palka P, Steinau HU. Major and lethal complications of liposuction: a review of 72 cases in Germany between 1998 and 2002. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008 Jun;121(6):396e-403e.

- 5. Hanke CW, Coleman WP III. Morbidity and mortality related to liposuction. Questions and answers. Dermatol Clin 1999 Oct;17(4):899-902, viii.

- 6. Rao RB, Ely SF, Hoffman RS. Deaths related to liposuction. N Engl J Med 1999 May;340(19):1471-1475.

- 7. Weinberg GL, Laurito CE, Geldner P, Pygon BH, Burton BK. Malignant ventricular dysrhythmias in a patient with isovaleric acidemia receiving general and local anesthesia for suction lipectomy. J Clin Anesth 1997 Dec;9(8):668-670.

- 8. Neal JM, Bernards CM, Butterworth JF IV, Di Gregorio G, Drasner K, Hejtmanek MR, et al. ASRA practice advisory on local anesthetic systemic toxicity. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2010 Mar-Apr;35(2):152-161.

- 9. Coleman WP III, Glogau RG, Klein JA, Moy RL, Narins RS, Chuang TY, et al; American Academy of Dermatology Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. Guidelines of care for liposuction. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001 Sep;45(3):438-447.

- 10. Rosenberg PH, Veering BT, Urmey WF. Maximum recommended doses of local anesthetics: a multifactorial concept. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2004 Nov-Dec;29(6):564-575, discussion 524.

- 11. Malamed SF. Systemic complications. Handbook of Local Anesthesia, 3rd ed. St Louis, CV Mosby, 1992. p. 310-331.

- 12. Malamed SF. Drug overdose reactions. Medical Emergencies in the Dental Office, 3rd ed. St Louis, CV Mosby, 1987.

p. 265-287.

- 13. Klein JA. Tumescent technique for regional anesthesia permits lidocaine doses of 35 mg/kg for liposuction. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1990 Mar;16(3):248-263.

- 14. Holt NF. Tumescent anaesthesia: its applications and well tolerated use in the out-of-operating room setting. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2017 Aug;30(4):518-524.

- 15. Klein JA, Jeske DR. Estimated maximal safe dosages of tumescent lidocaine. Anesth Analg 2016 May;122(5):1350-1359.

- 16. Weinberg G. Local anesthetic systemic toxicity and liposuction: Looking back, Looking forward. Anesth Analg 2016 May;122(5):1250-1252.

- 17. Dix SK, Rosner GF, Nayar M, Harris JJ, Guglin ME, Winterfield JR, et al. Intractable cardiac arrest due to lidocaine toxicity successfully resuscitated with lipid emulsion. Crit Care Med 2011 Apr;39(4):872-874.