A Qualitative Study on the Attitudes and Beliefs towards Help Seeking for Emotional Distress in Omani Women and Omani General Practitioners: Implications for Post-Graduate Training

Zakiya Q. Al-Busaidi

doi:10.5001/omj.2010.55

ABSTRACT

Objectives: This study aims to explore the attitudes and beliefs of Omani women attending primary health care and Omani general practitioners regarding help seeking behaviour for emotional distress. The study also intends to clarify the understanding of help seeking from both lay and professional perspectives in the context of Omani culture exploring factors related to doctors’ training and health care services.

Methods: A qualitative phenomenological study using semi-structured interviews was conducted at the Family Medicine Health Care Centre at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital. 20 lay informants (Omani women) and 10 professional informants (Omani family physicians) were interviewed.

Results: Two main sets of themes are presented in this study; 1). the original themes, which are presented in the results section and represent the descriptive level of analysis, and 2). the emergent themes are presented in the discussion section and represent the interpretive level of analysis. The original themes are: a) self help, with subthemes including the role of faith, talking and distraction. b) Health care and doctors, with subthemes including: reasons for seeing a doctor, reasons for not seeing a doctor, continuity of care, doctor-patient relationship and time. c) Traditional (folk) medicine. The emergent themes are: a) Talking b) Religious faith c) Cultural beliefs and d) The doctor’s role. Cultural and religious beliefs were found to shape the experience of help seeking in the study group. In addition, factors associated with doctor-patient relationship were found to play a major role in determining the help seeking behaviour of women experiencing symptoms related to psychological distress. Professional informants emphasized the role of their training, availability of supporting services, time and continuity of care. The study showed discrepancy between lay and professional informants’ beliefs regarding the role of family physicians in managing mental problems.

Conclusion: This study recommends paying more attention to factors related to cultural beliefs, doctor-patient relationship and family physicians’ role when planning health services and residency programs, and when planning research on aspects related to mental health in non-Western cultures.

From the Department of Family Medicine and Public Health, Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Al Khod, Muscat, Sultanate of Oman.

Received: 21 Feb 2010

Accepted: 02 May 2010

Address correspondence and reprint request to: Dr. Zakiya Q. Al Busaidi, Department of Family Medicine and Public Health, Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Al Khod, Muscat, Sultanate of Oman.

E-mail: zakiyaq@squ.edu.om

INTRODUCTION

Patients with mental health problems are high utilisers of primary health care.1 However, the management of psychological problems in general practice in the face of multiple competing demands is increasingly being seen as a far more complex task than previously appreciated.

Research indicates that health beliefs and help seeking behaviors are important factors for presentation to primary health care and the utilization of health services.2,3

Previous studies have established that several factors interact to determine help seeking behaviour. These factors include stigma and embarrassment, difficulty in discussing mental health problems, doctor-patient relationship, trust in health care professionals, the presentation of illness, previous experiences of illness, and overestimation of one’s coping abilities.4,5 In addition, social and cultural norms and beliefs have been shown to play an important role in the way people perceive health and illness and use available resources.6,7 People from different cultures may differ in their help seeking behaviour due to several reasons. Firstly, there may be variation in the way people experience the problem as a specific diagnosis or just symptoms. Secondly, different cultures can ascribe different meanings to symptoms.8,9 Thirdly, culture may influence the extent people are willing to disclose certain symptoms, especially because of perceived stigma.8 Finally, cultures influence the way symptoms are expressed and communicated when in contact with health care facilities and professionals.10

A quantitative study on the role of family member advice as a reason to seek health care in Oman showed that the advice of family members remains a strong mechanism for care-seeking in Oman.11 In the present study, exploratory qualitative methodology is used aiming to clarify the understanding of help seeking from both lay and professional perspectives in the context of the Omani culture, exploring factors related to doctor’s training and health care services.

METHODS

This study was part of a PhD thesis where qualitative approach was employed to study in depth the attitudes and believes of both women and general practitioners towards mental health.12 Two main groups of informants participated in the study: a lay informant group and a professional informant group. Semi structured interviews were used focusing on the following main domains; experience of contentment and discontentment, manifestation of distress, symptom attribution, and help seeking behavior.

In this article, only the categories related to help seeking are discussed. An interview guide was developed based on previous literature.6,7,13 While developing the interview guide, it was taken into consideration that questions had to be open-ended, inviting the interviewee to talk. In addition, questions were made neutral and jargon-free. Although the questions were placed in a certain desirable sequence, the researcher was aware that the interview did not have to follow the sequence on the schedule and that not every question needed to be asked or answered in exactly the same way with each informant. The researcher was ready to follow the novel avenues if they were going to add to the study but at the same time to keep the interview within the agreed domain.

In relation to help seeking behaviour, the key areas that were covered included:

Women’s own experience of emotional and psychological distress. For example: when you are discontent, how do you feel?

Actions taken by the informants as solutions. For example: When you feel distressed for any reason you mentioned, what do you do to feel better? Probe for self help, family, religion, spiritual, alternative medicine, traditional healers, medical practitioners other allied health and non conventional.

Women’s experience of the efficiency and usefulness of the actions and solutions used.

Questions and probes for professional informants were as follows; 1)What is the role of the GP in dealing with these problems? In what ways do you think you can help the patients and How confident do you feel dealing with these problems? 2) What are the other ways patients might seek help?

The questions were primarily developed in English and translated by the researcher into Arabic, using an Arabic-English English-Arabic dictionary when necessary.14 Before starting data collection, approval of the medical research and ethics committee at the Sultan Qaboos University was obtained in December 2001. Socio-demographic information, including contact information, educational level, occupation and demographic information, was obtained from all the informants before starting the interview.

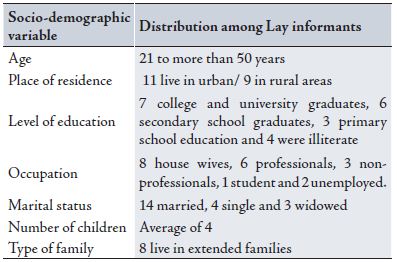

Lay informants (20 in total) were selected from among the Omani women attending the (FAMCO) health centre at the Sultan Qaboos University, using maximum variation sampling.15,16 They represented a spectrum of socio-economic status, educational levels, marital status and urban/rural backgrounds. (Table 1)

Table 1: Socio-demographic variables for the lay informants

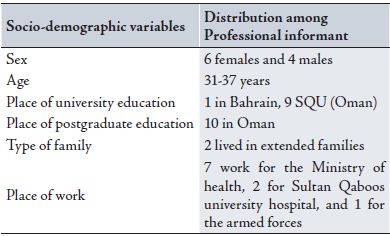

A homogenous sample was used to select professional informants in order to concentrate on issues related to medical education and the effect of the culture on this specific group.16 Male and female Omani general practitioners (GPs) who graduated from the Oman Medical Speciality Board (OMSB) family medicine program in 3 different years prior to the study were contacted by phone. A number of them were unavailable in the country or were difficult to contact. 10 GPs were willing to take part, 6 females and 4 males. (Table 2)

Table 2: Socio-demographic variables for the professional informants

A pilot study was conducted before starting the actual data collection. A total of 9 informants, 5 lay and 4 professional, were interviewed. The aim of the pilot study was to test the acceptability of the questions and the responses of the informants. This aim was achieved through critically appraising tape recordings giving attention to how directive the researcher was, the presence of leading questions and whether good cuing and propping were used. Changes and adjustments were made to the props and questions accordingly.

In the study, each interview began with a preamble setting the parameters of the interview (length and audio taping), assuring confidentiality and the possibility of withdrawing from the study at any stage. The informants were assured that there were no right or wrong answers, rather their ideas, views and experiences were the important contributions to the study. Consent was taken by the author prior to commencement of the interviews and all informants approached consented to the study except for two due to unavailability of time. All the interviews were conducted by the author in Arabic, which was the mother tongue for most of the informants. The recorded interviews were transcribed fully and verbatim, noting long pauses and non-verbal communications when thought to be important.

Although the author was not practising at the FAMCO health centre during the three years of the research period and none of the interviewed informants were patients of the researcher, there was still the potential that they could be in the future. In this study, the effect of the researcher was also important when interviewing the professional informants. As colleagues, the researcher had relationships of varying degrees with all of the professional informants. This kind of relationship must have affected the amount of spontaneity in the interviews both positively and negatively. Nevertheless, the author started the interview by explaining to the informants that they were free to say what they thought and felt without trying to correct them. The author believed that her being a woman and from the same culture as that of the informants would have a positive effect on the interviews and would help her understand the meaning and aid interpretation of the informants’ views. On the other hand, being from the same culture could have reduced the researcher’s ability to clearly recognise certain themes because she regarded them as normal.

The analysis was initiated based on the interview guide. The original themes derived from the interview guide were assigned to sentences and paragraphs of data and inferential codes of data were put together as lower levels or sub themes. The coding moved from the descriptive to the more interpretative and a set of emergent themes were developed. The analysis approach described in Miles and Huberman was used in this study in addition to what Smith describes as the “interpretive phenomenological analysis.”17,18

The transcripts were read several times. Interesting and recurring ideas in addition to striking words and sentences were marked on the right margin.

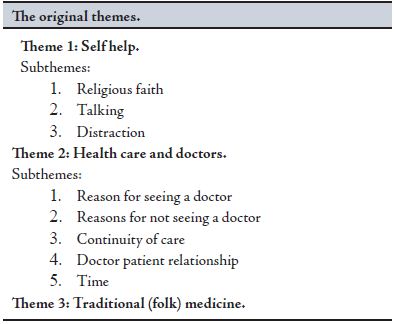

In the left margin, the original themes derived from the interview guide were assigned to sentences and paragraphs of the data. These were used as general themes while the recurring new ideas from units of data were put together as lower levels or sub themes. The end product of this process was that the original main themes were listed with a number of sub themes, or branches, derived from the data cluster together under the original themes. The original themes based on the interview guide were: 1. Self help, with subthemes including the role of faith, talking and distraction. 2. Health care and doctors, with subthemes including reasons for seeing a doctor, reasons for not seeing a doctor, continuity of care, doctor-patient relationship and time. 3. Traditional (folk) medicine. The themes are presented in the results section. (Table 3)

Table 3: Original themes

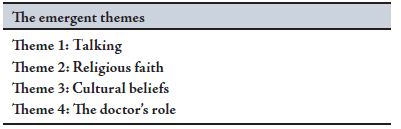

The second level of analysis was inductive in nature and was characterized by the emergence of a new set of themes that are different from the original themes. Some of these themes originally appeared as sub themes but they continued appearing recurrently across most of the original themes. These new themes were characterized by being pointers to the informants’ more general beliefs or style of thinking. They recurred with most of the informants cutting across a number of original themes present in both groups of lay and professional informants.

The emergent themes included; 1). Talking, 2). Religious faith, 3). Cultural beliefs, and 4). The doctor’s role. These themes are presented in the discussion section. (Table 4)

The computer package NVivo was used to aid in the analysis. Triangulation with multiple analysts was used as a method of verification in this study. It is defined as “having two or more persons independently analyse the same qualitative data and compare their findings.”16

Table 4: Emergent themes

For this study there were three different sessions of peer review conducted during the first stage of analysis. The analysts were given interview transcripts to read independently and analyse for content and structure. This was followed by a meeting session to discuss the themes developed and assess the level of agreement. The peer review meetings supported the results of the analysis, and there was a great level of agreement between the researchers.

RESULTS

In terms of the first theme”self help” and focusing on religious faith, all lay and professional informants agreed that faith was an important strategy of help. Faith was mentioned both as a belief and a practice. As a practice, informants talked about praying, reading the Quran, prayers and thikr as relieving.1 Reading the Quran was the most commonly mentioned practice by all of the informants to relieve emotional distress. Informants stressed that the Quran has to be read with concentration and devoutness in order for the reading to have a contenting effect.

“When you read with conviction…you are reading Allah’s words with complete submission and devoutness. That will have an effect for sure.” Lay informant 11 explained.

Other aspects of Islamic faith, mentioned by the informants which were regarded as helpful included endurance and believing in fate. Informants declared that their belief in fate helps them accept difficult situations that cannot be changed and carry on with life instead of dwelling on the past. Not believing in fate was thought to lead to difficulties and psychological problems.

Professional informants also stressed the importance of faith on their patients’ wellbeing. They talked mainly about praying and reading the Quran. They agreed that if treatment involves reading the Quran, they will not advice their patients against it. On the contrary, some professional informants said that they would encourage their patients to read the Quran as a form of treatment either on its own or in addition to medical treatment.

“Reading the Quran is a good thing. I would tell the patients myself to read the Quran or pray. As a doctor in this culture, I can use it for treating my patients.” Professional informant 4 explained.

The Professional informants shared with lay informants the significance of believing in fate. They mentioned that this belief was helpful to their patients and made patients deal with difficult situations better.

Talking was another subtheme that all the lay informants and six professional informants mentioned as a strategy for help. The different ways of talking mentioned included confiding, chatting and complaining. The most commonly mentioned people as trusted ones to confide in were family members, especially sisters and mothers followed by friends.

“Talking makes you feel better; part of your distress will be relieved... I talk to my aunt because I feel she is close to me. I tell her about everything that disturbs me.” Lay informant 5.

Chatting to family members, friends and neighbours was also mentioned as relieving. The difference between chatting and confiding is that informants choose to confide in certain people and they usually do that either to relieve a sense of distress or in order to solve a problem. Chatting, however, is aimed at trying to forget about the distressing subject and avoid thinking about it. Informants said that they would talk to a doctor if they needed someone to talk to, but could not find a suitable person. Lay informants linked talking to understanding. Feeling understood by family members, husband and doctors was encouraging for informants to talk. On the other hand, lack of understanding will deter the informants from talking about their distress.

Professional informants were aware that talking lead to contentment and satisfaction in the patients. They mentioned talking as a therapy and most of them agreed that listening to the patients was essential in treating emotional problems. In addition, doctors agreed with the lay informants that people who did not talk and “kept things inside” were more prone to stress and psychological problems. Some professional informants expressed the need for more “talking therapies.” They thought that general practitioners as well as psychiatrists need to spend more time on “talking therapies.” However, some doctors talked about their lack of experience with counselling and psychotherapy.

“Sometimes I feel that I don’t have enough experience. I need more experience and maybe to attend courses in counseling.” Professional informant 6.

All lay informants talked about avoiding thinking (blocking ‘negative’ thoughts or distraction) of distressing subjects in order to feel better. However, none of the professional informants talked about distraction as being helpful. Lay informants described distraction as trying to forget about the problem, getting busy with other things and not to keep the problem on their minds. Different activities were mentioned as ways of getting busy and avoiding thinking about distressing subjects. Most of the informants talked about going out for visits and socializing as a way of avoiding thinking.

“I try to forget about the reasons for my distress. I know it is not possible to forget but I try to get busy with other things. I try not to be alone, I go out with people. I talk to them, but I try not to talk about the distressing subject.” Lay informant 17.

In the second theme, all informants talked about issues related to health care (the doctor) in relation to help seeking. They spoke about the doctor’s role, reasons for seeing or not seeing a doctor, time constraint, continuity of care and the stigma associated with mental illness. Professional informants talked about their role in treating patients with emotional distress and the difficulties they face in diagnosing and treating patients with medically unexplained symptoms.

The lay informants mentioned several reasons for seeing a doctor for their distress. For example, worry about having a serious disease behind the symptoms such as high blood pressure, heart disease or cancer. They said that they would see a doctor if symptoms were persistent or if they were severe. In addition, they said that if they had psychological or emotional distress that was beyond their abilities to deal with, then they would see a doctor. Another reason commonly given for seeing a doctor was to receive advice related to their social problems and to help them solve the complicated problem.

“It is possible if I have a problem going on for a long time, distressing and I cannot find a solution for it…a distressing problem that is psychologically tiring and causing me worries and loss of sleep. In that case I will see a doctor.” Lay informant 14.

Professional informants agreed that their role is not limited to listening to the patient but also included trying to help the patient solve his/her problems by suggesting solutions and discussing these solutions with him/her. However, they didn’t mention the relationship between help seeking and the severity of the symptoms.

The lay informants talked about the stigma surrounding mental illnesses as a reason for not seeing a doctor in cases of distress. Stigma was mentioned in association with the word majnoon.1

“Yes, some people go (to see psychiatrists) but you know Omanis they do not believe in things such as psychological problems. For example, if someone has a psychiatric disease, they will say he is crazy. For example, there are people who are disabled and people will be laughing at them.” Lay informant 16.

Half of the professional informants talked about the problem of the stigma affecting their patients’ attitude towards mental illness. Doctors mentioned words such as “crazy” and “mad” to describe what some people in Oman think of psychiatric patients. Moreover, professional informants believed that stigma resulted in patients denying psychological symptoms in order to avoid the label of mental illness.

“Some of the patients try to hide it; they do not even show a depressed mood. They know what you are looking for so they will try to hide it and not look depressed. Because it is considered a stigma in the Arab world to be depressed. It is regarded as madness. They are afraid that you might refer them to a psychiatric hospital.” Professional informant 8.

Another reason given by the informants explaining their choice not to see a doctor for their distress was when the informant believed that “it was normal to get such symptoms” and they did not need to see the doctor for such symptoms.

Most of the lay informants thought it was not the general practitioner’s role to treat problems related to psychological and emotional distress. When they thought that they needed to see a doctor for such problems they mentioned seeing a psychiatrist. A specialist, in general, is perceived as more knowledgeable and the role of the general practitioner in that case would be to refer the patient or to give him/her symptom relieve.

“I can see a general practitioner. Maybe if the cause is physical but if the general practitioner does not find anything, then there is nothing wrong and my body is normal. Then I should be refereed to a psychiatrist.” Lay informant 8.

Contrary to the lay informants’ view, professional informants thought that it was the general practitioner’s role to treat mental problems, especially mild anxiety and depression.

“I think it is the family physician’s duty to treat these problems. The family physician will be able to understand the patient, his family and the community that is affecting the patient.” Professional informant 4.

Follow up and continuity of care were also mentioned to be important. They were perceived by lay informants as the responsibility of the doctor.

“So if he can advise you and follow up your case, not just see you once and that’s it…if the doctor follows up the patient, that will make the patient feel someone is interested in helping her.” Lay informant 17.

Professional informants agreed with the lay informants regarding the importance of continuity of care, but to them it was the responsibility of both the doctor and the patient, but mostly of the patient.

“The problem is that they will see you a few times and then they will disappear. Next time you see them, you will discover that they have been to several other doctors. There is no continuity because the idea of family medicine is not there, so even if you make the diagnosis on the first visit and you ask them to come again they will disappear.” Professional informant 11.

Most lay informants talked about communication as an important factor in determining doctor-patient relationship. If the informant does not feel that the doctor is close and understanding, they may decide not to talk or even to discontinue the treatment.

“Why keep quiet about it. It will only lead to more diseases. But it depends on the doctor. Sometimes when you enter the consultation room you feel comfortable with the doctor. But sometimes you feel forced to tell the doctor because you worry you might get worse, so you prefer to tell the doctor that you are not sleeping well because you have problems.” Lay informant 15.

Smiling and greeting the patient in a nice way was mentioned as positive characteristics in the doctor, which is sometimes lacking in the patient’s own general practitioner.

“Why do you think we like to go to private practice? Because the doctor use nice words such as “welcome”, “how are you”, and so forth... These are only words but we miss them, we miss them with our own general pactitioners.” Lay informant 7.

The informants perceive doctors who do not smile and greet patients in a friendly manner as arrogant and uncaring. Professional informants also thought that the doctor-patient relationship is important in the management of patients.

“The most important thing here is the doctor-patient relationship; so if I already know the patient, there is a relationship between me and the patient, it will be easier for me to notice any change in the patient. As his doctor, I will notice that there is something different about the patient.” Professional informant 4.

On the other hand, most professional informants talked about the issue of time as a restricting factor where treatment is concerned.

“We can do a lot, starting by educating people that illnesses can be caused by mental health problems. But the problem is the time constraint that sometimes limits us from interacting fully with patients, giving them “good ears”, listening to their problems and offering them good management.” Professional informant 1.

In addition, they mentioned that treating mental health problems was more time consuming compared to usual consultations in general practice. Only two lay informants mentioned lack of time as a problem affecting their presentation of psychological problems to health care.

“Doctors are not all the same. Some doctors treat you well, but some act as if they don’t want to know you at all. They see you in a short time. Doctors in our local hospital always seem to be in a hurry.” Lay informant 19.

All the lay informants talked about seeking a Muttawa4 (the traditional healer) for help. Both lay and professional informants agreed that there were two types of Muttawa. The first type is the religious man who is using Quran for treatment and usually does not ask for money in return for their services. The second is a crook who is cheating people in order to get money, and usually does not give them any actual relief or help. Lay informants mentioned stories describing their experience with helpful and unhelpful Muttawa. As far as the reasons for seeing Muttawas are concerned, most lay informants said that “jinn” possession and “hasad” (evil eye) were the main reasons for seeking Muttawas’ help. Other reasons given included thinking and psychological problems.

“…For example, stress. She could be thinking of anything, or could be having problems related to relationships. A problem within a relationship can affect the person and make her think. It can affect her and make her neglect her studies or work. She may neglect herself and family. This will affect her psychological [emotional] state and become like crazy, so her family will have to seek a Quran reader for help.” Lay informant 2.

Most professional informants agreed that a Muttawa who read Quran or used it in treatment may be able to help the patient and they said that they would not advice their patients against this kind of treatment. In addition, some professional informants believed that if the reason for distress was a result of “jinn”, then this treatment may be helpful. However, a few professional informants disagreed, saying that Muttawa did not have any role to play in the management of mental problems and added that they might interfere and advise the patient not to visit a doctor.

DISCUSSION

In terms of the emergent themes, talking was presented as a major emergent theme in this study. All the informants (professional and lay) stressed that talking was an essential and effective strategy of help in cases of distress, thus supporting findings of previous literature.13,19,20 In addition to being a remedy, confiding within a relationship has been found to be important in preventing psychiatric problems.21 Patients make the choice and specifically decide not to talk to the doctor about their distress. Some informants explained that it was inappropriate culturally to talk to the doctor about their private lives. What patients consider appropriate to present to the doctor is important when presenting to primary health care and have been found to affect patients’ choice to present psychosocial issues to the general practitioner.22

Lay and professional informants repeatedly mentioned that religious faith as a source of help. In all of these aspects, faith was mentioned both as a belief and a practice. As a belief, it was a reason for contentment and a source of help. The reward of faith has also been mentioned. Informants talked about reward in the form of feelings of satisfaction and contentment and in the form of good luck, success and achievement of their goals. They also mentioned that this belief gave them a feeling of optimism and hope for the future. In general, professional informants shared the conviction of lay informants that faith, both as a belief and a practice, was an essential strategy for help.

Religion was mentioned as a source of help in other studies involving women. In these studies women stressed that everyday experiences and practices required spiritual mediation and prayers.23 It has been suggested in previous literature that faith healer practices should be grounded within the guidelines of treating physical and mental illnesses.24

In this study, lay and professional informants shared cultural beliefs such as the idea that “jinn” possession is something a doctor cannot deal with and requires the experience of a Muttawa or a spiritual healer. Once “jinn” possession is suspected, people surrounding the patient take the responsibility of choosing the right Muttawa. Some doctors agreed that if something like this happened to a close person, they would take her to see a Muttawa.

Moreover, patients may have difficulty presenting emotional problems because of fear of stigmatization.25,26 In this study, most lay informants and some professional informants shared the idea that stigma related to psychological problems was common in the Omani culture and affected patients’ decision to present their symptoms to the doctor. However, lay informants who mentioned the problem of stigma denied that it would affect their presentation to health care facilities although they were aware of it. The reason for this could be that the researcher is a doctor and educated lay informants do not want to admit that they will give in to the pressure of the culture in spite of their knowledge of mental illness. In addition, in this study as well as previous research, expectations related to doctor-patient communication were found to be shaped by cultural norms and not by what is professionally expected of a doctor.

There was a discrepancy between what the professional informants believed their role to be and what the lay informants thought the family physician’s role was. Professional informants thought that it was their role to treat what they called “simple cases” of mental disorders, using not just medications but also psychotherapy. However, in this study, if the extent of the problem necessitated seeing a doctor, patients preferred to see specialists instead of general practitioners.

A general practitioner was not considered to be knowledgeable about psychiatric diseases and their role was merely to refer patients to psychiatrists. The explanation for this finding could be that patients in Oman are not familiar with the role of a general practitioner and the knowledge and experience general practitioners may have. In the Omani community, general practitioners are still viewed as doctors who graduate from medical school without any postgraduate education or experience. Patients make the choice and specifically decide not to talk to doctors about their distress. What patients consider appropriate to present to the doctor is important when presenting to primary health care and has been found to affect patients’ choice to present psychosocial issues to the general practitioner.22 In addition, cultural variations with regards to what the patients’ consider an illness have been shown to affect the patients’ choice not to communicate what they consider non-medical.13,26,27

The severity of symptoms was also mentioned as a factor affecting the informants’ choice to see a doctor. This finding is supported by a previous study that showed that some patients decide not to talk to general practitioners about their distress, because they feel that their problem is not bad and that they can cope with it.26 Doctors’ interviewing behaviours and previous experience with something the doctor did or said in the past have been shown to deter patients from talking to the doctor about their emotional distress.25,26 In this study, lay informants differentiated between doctors who were interested to help and listen and those who were only interested to treat their symptoms.

As a result, informants would only talk to a doctor who showed interest in listening to their problems and would especially do so if the doctor asked them directly about the reason for their distress. In addition, lay informants referred to nonverbal communications as important. They interpret what they consider good non-verbal cues from the doctor as signs of interest, care and understanding. Smiling doctors are considered welcoming and interested and are mentioned as another reason that encourages talking. Non-verbal cues such as eye contact, smiling and humour were shown to be important in building a good relationship with the patients.27

In a culture where smiling and greeting people, even if they are strangers, is considered a good manner, the behaviour of busy young doctors is considered unacceptable and misinterpreted by the public as arrogance. Furthermore, most Omani doctors are young adults and are required, according to the traditional Omani culture, to show respect to older individuals.

Most professional informants in this study find the diagnosis and management of mental health problems difficult. The informants have proposed several explanations. One is the physical presentation of psychological and emotional distress that might sometimes be misleading. Presenting psychological problems with physical symptoms in general practice has been associated with lower recognition of psychiatric disorders in primary health care.28,29 However, a few professional informants said that they did not have difficulty diagnosing and managing mental problems because they felt confident in their knowledge and they depended on good doctor-patient relationship.

Constraints about the consultation time are a common reason for dissatisfaction for both doctors and patients in general practice.30 There is evidence that psychosocial discussions result in longer consultations.31 In this study, professional informants talked repeatedly about the shortage of time as a factor restricting diagnosis and management of patients with psychological problems. According to most of the professional informants, the problem of time constraints is difficult to solve but some think arranging regular follow up visits may be a solution to the problem. Only two lay informants mentioned restriction of time as a problem in general practice.

Most professional informants emphasized the need for talking therapies but admitted their lack of knowledge and experience in this area and psychotherapy in general. Some professional informants asked for more training while some saw that the solution was to have more social workers, counsellors and psychotherapists. The same was shown in previous studies where general practitioners talked about solutions to their patients’ problems that are lying outside their own professions.16 The big shortage of social workers and psychotherapists in the country explains the doctors call for more help from outside the profession.

Continuity of care through regular visits to the same primary care physician has been described as essential in treating patients in primary health care. Through regular visits, the patient does not need to develop new symptoms in order to receive medical attention. In addition, regular visits to the same general practitioner help tackle problems and address new issues as they appear.32,33 Both lay and professional informants stressed the importance of continuity of care. However, lay informants believed it to be the responsibility of the doctor, while professional informants thought it was the responsibility of the patient. The appointment system in health care is relatively new in Oman, so is the concept of the catchment area where patients living in a certain area are assigned to a single health centre and ideally seeing the same general practitioner for all of their problems.

Being a qualitative study, the results of this study cannot be generalized to the population in Oman as the aim was to gather in depth information. In addition the study was conducted in Muscat and therefore, it may not reflect the experience of patients in other parts of the country.

CONCLUSION

Doctor-patient relationship was found to be important in determining patients’ decision to present their distress to the doctor. Doctor’s attitude during the consultation was found to be an important factor determining patients’ decision to talk about their psychological distress. Issues related to nonverbal communication, the doctor showing interest and empathy, and the doctor taking cultural considerations towards the patient were found to be important. Cultural and religious concepts related to health beliefs and those which affect patients’ attitudes towards health should be emphasized in the residency training programs of specialities such as family and community medicine, and psychiatry. In addition, cultural issues should play a role in the teaching of consultation techniques and communication skills of general practitioners. A significant finding in this study was the fact that talking was an important strategy for help. However, most doctors recognized their deficiency in skills related to talking therapy, counselling and psychotherapy.

Therefore, more concentration on such skills is required during the four years of training and when planning continuing professional development programs. At the time of the study, the training of Omani general practitioners involved a two months rotation in psychiatry. In view of the commonality of psychiatric problems in primary health care, OMSB has recently extended this training to four months. This step will hopefully improve the training of family medicine residents if continuous assessment of the content and the outcome of the rotation take place. More attention should be paid to improve certain aspects of health services in order to improve the recognition and management of mental health problems.

Continuity of care should be encouraged through better implementation of the appointment system, and regular follow up visits to the same general practitioner. There is also need to educate the public regarding the importance of continuity of care and keeping regular appointments with their doctor. Moreover, more autonomy should be given to trained and experienced general practitioners in managing their own practices regarding issues such as availability of medications. There is need for health education of patients and the community regarding the role of general practitioners, especially in relation to the management of mental health problems. Overall, more qualitative research is needed in the area of patients’ understanding of their health and the way they experience and deal with stress within the context of their culture.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank the informants who participated in this study and the staff at the family medicine and public health, SQUH. My thanks also go to my PhD supervisor, Dr Margaret Oates, and to Dr Karen carpenter and Dr Amal Shoaib for taking part in the peer review.

-

Hartman TO, Rijswijk E, Ravesteijn H, Hassink-Franke L, Bor H, van Weel-Baumgarten E, et al. Mental health problems and the presentation of minor illnesses: Data from a 30-year follow-up in general practice. The European Journal of General Practice 2008; 14: 38-43.

-

Barsky AJ. Hidden reason some patients visit doctors. Annals of Internal Medicine 1981; 94 (4): 492-498.

-

Roberts SJ. Somatisation in primary care: The common presentation of psychological problems through physical complaints. Nursing Practice 1994; 19 (5): 50-56.

-

Wells JE, Robins LN, Bushnell JA, Jarosz D, Oakley-Browne MA. Perceived barriers to care in St Louis and Christchurch: reasons for not seeking professional help for psychological distress. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 1994; 29 (4):155–164.

-

Wrigley S, Jackson H, Judd F, et al. Role of stigma and attitudes toward help-seeking from a general practitioner for mental health problems in a rural town. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2005; 39 (6):514–521.

-

Kleinman A M. Patients and Healers in the context of culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980.

-

Katon W, Ries R K and Kleinman A M. The Prevalance of Somatization in Primary Care. Comparative Psychiatry 1984; 25: 208-215.

-

Hinton DV, Howes D, Kirmayer L. Towards a medical anthropology of sensation: Definition and research agenda. Transcultural Psychiatry 2008; 45(2): 142-162.

-

Al-Adawi S H. Zar: Group distress and healing. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 2001; 4 (1): 47-61.

-

Kirmayer LJ, Young A, Robbins JM. Symptom attribution in cultural perspective. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 1994b; 39 (10): 584-595.

-

L. Relatives’ Advice and Health Care-Seeking Behaviour in Oman. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal 2009; 9 (1): 246-271.

-

Al-Busaidi Z. Rethinking Somatisation: The Attitudes and Beliefs about Mental Health in Omani Women and Their General Practitioners. PhD Thesis, School of Community Health Sciences, University of Nottingham, UK, 2005.

-

Oates M R, Cox J L, Neema P, Asten P, Glangeaud-Freudenthal N, Figueiredo B,et al. Postnatal depression across countries and cultures: A qualitative study. British Journal of Psychiatry 2004; 184: 10-16.

-

Baalabki, M. and Baalabki, R. Al-Mawrid Dictionary: English -Arabic, Arabic-English. Beirut: Dar-El-Ilm Lilmalayin, 1999.

-

Al-Busaidi Z. Qualitative research and its application in health care. Sultan Qaboos Medical Journal 2008; 8 (1): 11-19.

-

Patton M Q. Qualitative Evaluation Methods. CA: Sage, 2002.

-

Miles M, Huberman, M. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 1984.

-

Smith JA, Harre R, Van Langenhove L. Rethinking Methods in Psychology.London: Sage Publications, 2001

-

Baarnhielm S. Making sense of suffering: Illness meaning among somatizing Swedish women in contact with local health services. Nord Journal of Psychiatry 2006; 54 (6): 423-430.

-

Baarnhielm S. Turkish migrant women encountering health care in Stockholm: A qualitative study of somatisation and illness meaning. Culture Medicine and Psychiatry 2000b; 24 (4): 431-452.

-

Mirza I and Jenkins R. Risk factors, prevalence, and treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders in Pakistan: Systematic review. British Medical Journal 2004; 328 (7443), 794-797.

-

Barry CA, Bradley CP, Britten N, Stevenson F, Barber N. Patients unvoiced agendas in general practice consultations: Qualitative study. British Medical Journal 2000; 320 (7244): 1246-1250.

-

Walters V, Charles N. “I just cope from day to day”: Unpredictability and anxiety in the lives of women. Social Science and Medicine 1997; 45 (11): 1729-1739.

-

Aikins A D. Healer shoping in Africe: New evidence from rural-Urban qualitative study of Ghanaian diabetes experience. British Medical Journal 2005; 331, 737-742

-

Cape J, McCulloch Y. Patients’ reasons for not presenting emotional problems in general practice consultations. British Journal of General Practice 1999; 49 (448): 875-879.

-

Hansen J P, Bobula J, Meyer D. Treat or refer: Patients’ interest in family physician involvement in their psyhcosocial problems. Journal of Family Practice 1987; 24 (5): 499-503.

-

Simon G E, VonKorff M, Piccinelli M, Fullerton C, Ormel J. An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. The New England Journal of Medicine 1999; 341 (18): 1329-1335.

-

Wright E B, Holcombe C H, Salmon P. Doctor’s communication of trust, care and respect in breast cancer: Qualitative study. British Medical Journal 2004; 328: 864-867.

-

Bridges K, Goldberg D P. Somatic presentation of DSM III psychiatric disorders in primary care. Journal of psychosomatic Research 1985; 29 (6): 563-569.

-

Weich S, Lewis G, Donmall R, Mann A. Somatic presentation of psychiatric morbidity in general practice. British Journal of General Practice 1995; 45 (492): 143-147.

-

Morrison I, Smith R. Hamster health care: Time to stop running faster and redesign health Care. British Medical Journal 2000; 321 (7276): 1541-1542.

-

Wilson A. Consultation length in general practice: A review. British Journal of General Practice 1991; 41 (344): 199-122.

-

Al-Azri M, S. Patients’ Views of Interpersonal Continuity of Care in Four Primary Health Care Centres of Urban Oman. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal 2009; 9: 287-295.

How to cite this article

Al-Busaidi ZQ. A Qualitative Study on the Attitudes and Beliefs towards Help Seeking for Emotional Distress in Omani Women and Omani General Practitioners: Implications for Post-Graduate Training. OMJ 2010 July; 25(3):190-198.

How to cite this URL

Al-Busaidi ZQ. A Qualitative Study on the Attitudes and Beliefs towards Help Seeking for Emotional Distress in Omani Women and Omani General Practitioners: Implications for Post-Graduate Training. OMJ [Online] 2010 July; 25(3):190-198. Available at http://www.omjournal.org/OriginalArticles/FullText/201007/FT_AQualitativeStudy.html.