Assessing Factors that affect Childbirth Choices of People living positively with HIV/AIDS in Abia State of Nigeria

Ezinne E. Enwereji, Kelechi O. Enwereji

Enwereji EE, et al. OMJ. 25, 91-99 (2010); doi:10.5001/omj.2010.27

ABSTRACT

Objectives: Poor interpersonal relationships with women especially those living positively with HIV/AIDS can make them take risks that would expose their new born and others to infection during childbirth. The factors that influence childbirth choices of people living positively with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) deserve attention. Sometimes, women, especially PLWHA, for several reasons, resort to the use of other health care services instead of the general hospitals equipped for ante-natal care (ANC). This study aims to identify factors and conditions that determine childbirth choices of PLWHA in the Abia State of Nigeria.

Methods:A cross-sectional descriptive study was carried out using a total sample of 96 PLWHA who attend meetings with the network of PLWHA and also a purposive convenience sample of 45 health workers. Data collection instruments were questionnaire, focus group discussions and interview guides. Data was analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively using simple percentages.

Results: There was a low patronage for hospital services. A total of 79 (82%) PLWHA did not use hospital services due to the lack of confidentiality. In total, 61 (64%) PLWHA had their childbirth with Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs) at home. Embarrassment, rejection, interpersonal conflicts with health workers, non-confidentiality, cultural stigma and stigmatization were among the factors that encouraged childbirth choices. On the whole, 82 (85%) of the PLWHA discontinued ANC services because of stigmatization.

Conclusion: Poor interpersonal relationships between health workers and PLWHA facilitated PLWHA childbirth choices more than other factors. PLWHA and health workers termed management of belligerent tendencies against each other as their greatest concern. Therefore, concerted effort is needed to improve health workers/PLWHA relationship in hospitals. This would minimize factors and/or conditions that encourage HIV infection. Exposing PLWHA to factors that influence childbirth at home demonstrates high risks of mother-to-child transmission, infection to others and obstetric complications.

From the Department of Medicine, Abia State University, Uturu, Abia State, Nigeria

Received: 05 Feb 2010

Accepted: 27 Mar 2010

Address correspondence and reprint requests to: Dr. Ezinne E. Enwereji, Department of Medicine, Abia State University, Uturu, Abia State, Nigeria

E-mail: hersng@yahoo.com

Enwereji EE, et al. OMJ. 25, 91-99 (2010); doi:10.5001/omj.2010.27

INTRODUCTION

Enlightening ‘people living positively with HIV/AIDS’ (PLWHA) on the need to use health care services so as to minimize mother-to-child transmission is an important aspect of HIV prevention program.1 In Africa including Nigeria, reproductive health services have not been very well patronized by PLWHA especially females despite the overwhelming knowledge and skills of health workers in care of PLWHA.2,3 It is felt that noting factors and conditions that determine childbirth choices of PLWHA, and deterrents to the use of health care services would be beneficial especially this period when many countries including Nigeria are committed to reduce their HIV prevalence rates.

Nigeria is one of the countries with high HIV prevalence rates. Ministry of Health’s 2007 HIV/Syphilis sero-prevalence sentinel survey revealed a national HIV prevalence of 5% among women attending antenatal clinics aged between 15-49 years. With this high prevalence rate, it is necessary to encourage conditions that could positively influence the reduction in HIV/AIDS prevalence.

In Nigeria, like most developing countries, males control household expenditure and decision-making in families including reproductive health matters.4 Females’ lack of decision-making power limit their access to health care and this could negatively affect maternal health outcomes.5,6,7 Males as the principal decision-makers on health care seeking, allow little communication with females as to their choice of health care during pregnancy and childbirth.8,9

Culturally, there are conditions that influence childbirth choices of females including those that are HIV positive. In cases of suspected extra-marital sexual relationships that probably result to pregnancy, childbirth would be at home preferably in a secluded place where elderly women in the community would watch for signs of protracted labour. If protracted labour occurs, it presupposes culpability and the affected woman would be abandoned. If eventually she dies in the process of childbirth, her cadaver with that of her newborn would be deposited in a thick forest usually far away from residential areas. Today, Christianity has modified some of these practices, but nevertheless, some rural communities are still practicing them.

Cordial relationship between health workers and PLWHA is very crucial in acceptance and utilization of health care services.10,11 Studies have shown that good interpersonal relationship increases health seeking behaviour of PLWHA.12,13 Individuals including PLWHA are unlikely to seek health care if they suspect disrespect, loss of privacy, stigmatization, rejection, and discrimination during health services.14-17 Also, the need to encourage PLWHA to have babies in hospitals where professionals could handle emergencies, blood and “mess” to minimize HIV transmission should not be over emphasized. It is in the attempt to contribute to further reduction of HIV prevalence in Nigeria, especially mother-to-child transmission, that the researchers undertook the study.

The study objectives include determining the factors that discourage PLWHA from having childbirth in hospitals where professional services are available. But also, to note the extent to which PLWHA encourage prevention of mother-to-child transmission. The study equally aims to identify the obstacles women/PLWHA face in accessing antenatal and obstetric services. Understanding these factors could be used to improve services in rural areas.

Abia State is located in the South-eastern part of Nigeria and comprises of 17 local government areas with a common language. The population is over 3 million (1991 census report). However, the population has dropped to a little over 2 million (2006 draft census report), probably as a result of high HIV prevalence rate that stands at 3.6%.2 Notwithstanding this prevalence, only a negligible number of people who are HIV positive belong to the network of PLWHA. Others are not interested to identify with the network. Out of the number that registered with the network, only a few accept to attend meetings, others conceal themselves in the rural areas.

There are also few health centers and general hospitals with qualified health care professionals that provide “antenatal’’ (ANC) services. Moreover, these “antenatal’’ ANC services are linked to STI services at all health care levels in Abia State. In addition, HIV pre- testing and post-testing counseling are also available.

In Abia State, about 50% of people in the communities have neither access to potable water nor good roads. Most people depend on stream water for domestic use. Only few individuals afford borehole water. Those who cannot fetch water from the stream depend on water they purchase from boreholes.

Also, approximately 30% of the land mass is hilly. Gullies made by erosion make means of transportation slightly difficult. There are tarmac roads in the major roads connecting rural areas, while the roads leading to the rural areas are dirt roads. About 85% of houses are zinc-roofed with the walls made of either un-burnt bricks or mud. The remaining houses are thatch-roofed with the walls made of mud.

The main means of livelihood in the rural areas is subsistence farming. It is estimated that 75% of the people earn their living from subsistence farming. Only about 7% of people in the rural areas have paid jobs. The rest earn their living by working as hired labourers to other farmers.

The study was a cross-sectional descriptive study. The study used both qualitative and quantitative methods. Qualitative research process enabled the researchers to assess the views of PLWHA on childbirth choices. This also helped to promote the participation of the samples in the study. The study explored the views of PLWHA on risks of having childbirth elsewhere other than hospitals.

The study population was comprised of PLWHA as well as health workers. A total sample of 96 members of network of PLWHA (56 females and 40 males) was used. These are individuals who have made public their sero-status and are active in the network activities. They present themselves regularly at the monthly network meetings. The President of PLWHA listed and invited these members for interview. In addition, a list of all health workers working in health institutions in rural and semi-urban areas was obtained from Ministry of Health. The health workers provide health care services to every individual including those living positively with HIV and AIDS. A purposive convenience sample of 45 health workers (20 in semi-urban and 25 in rural area) was studied. Network of PLWHA was used because of the difficulty the researchers encountered in locating PLWHA. Individuals who are HIV positive are reluctant to disclose either their sero-status or that of others. The researchers considered it safer to use the network of PLWHA whose sero-status is already known. The health workers were also studied because of their expected roles in the treatment, care and support of PLWHA. They were considered the most knowledgeable and trusted group in the community who should care and protect the interest of PLWHA.

Males (PLWHA) were included in this study because of the stringent roles men play in decision-making in the family. Culturally, males take all decisions including where females seek care, and childbirth. Including male PLWHA in the study was designed to overcome these practical obstacles. It was considered that planning interventions that require behavioural changes, long-term thinking and decision-making for females without involving males would have no positive impact.

Data was collected with qualitative and quantitative instruments. Data collection involved three methods, these were; questionnaire, focus group discussions and interview guides. These contained both structured and unstructured questions. 15 focus group discussions (10 for PLWHA and 5 for health care workers) were conducted to explore the conditions that influence childbirth choices of PLWHA. Each focus group had 9-10 participants. The health workers were aggregated by discipline while PLWHA were aggregated by sex, age and marital status during the focus group discussions.

Two training and briefing sessions were conducted for three research assistants who carried out the interview and the focus group meetings. One session was for data collection using in-depth interview guide, and the other session was for note-taking, observing and moderating using focus group discussion guides. During the training sessions, the research assistants were acquainted with the objectives of the study. This ensured uniform data collection because the same interviewing/note-taking standards and procedures were adopted. All discussions were conducted in the local language and also tape-recorded. This enabled participants especially the illiterates to take active part in the discussions. Participants were encouraged to talk freely among themselves. The tape-recorder used for focus group discussion was checked regularly to ensure its dependability.

Two types of instruments characterized by open-ended and closed-ended questions, one for PLWHA and the other for health workers were used.

The University Ethical Committee vetted and approved the study before its commencement. Following this approval, permission to conduct the study was obtained from Abia State Ministry of Health and also from the President of network of PLWHA in the State. Furthermore, the consent of all active PLWHA in the network and that of the health workers was sought and obtained. This enabled the researchers to collect information from the participants.

The instruments used for the study did not request the participants to write their names or to give any details that would identify them. In addition, statements of confidentiality were given. During the study, participants were briefed on the study objectives and permission to tape-record the session was sought and guaranteed.

The population of PLWHA studied was mainly people that belonged to the network who also attended network meetings. Those that neither belonged to the network nor attended network meetings were excluded. This means that the study only included the PLWHA who were available during network meeting. It may be possible that the PLWHA excluded from this study are the ones that encourage PMTCT by using hospital services during childbirth. The findings therefore, may not be generalized for all PLWHA in Abia State.

A major strength of this research is that PLWHA were encouraged to identify problems militating against the use of health care services provided to them by health workers. They were also encouraged to analyze the causes of such problems from their own perspective. Through this process, the PLWHA were not only aware of the result of the study but also they made important contribution into the research process which assisted the researchers in identifying strategies for improving the health services.

The study was mainly carried out with PLWHA who belong to an organized body such as the network of PLWHA. The instrument for study was tested with members of other organized bodies offering similar functions to some individuals. Three trained research assistants were used for data collection.

Data was analyzed, qualitatively and quantitatively. Tables with simple percentages were utilized. Focus group discussions were recorded, transcribed, and translated. The transcripts were reviewed to identify the themes. Data was manually coded and categorized according to the themes. Related ideas and information from both the focus group discussions and interview guide were pooled together and reported. Data reporting was conducted in two sections, one for PLWHA and the other for health workers. In addition, important information and/or ideas from participants’ specific responses were highlighted. Simple percentages were used to clearly identify the specific factors that encouraged PLWHA childbirth choices at home. This enabled the researchers to note realistic intervention techniques needed to create positive changes.

RESULTSThe PLWHA studied were comprised of 56 (58%) females and 40 (42%) males between the ages of 20-69 years. Their education and occupation varied. A total of 32 (33%) had no formal education, 16 (17%) had tertiary education, 27 (28%) had primary school education, while 21 (22%) had secondary school. In terms of occupation, 29 (30%) were artisans, 9 (9%) were civil servants, while 58 (60%) were subsistence farmers. With regards to their place of residence, 63 (66%) lived in rural areas while 33(34%) lived in semi-urban areas. Out of those studied, 18 (19%) were single, 39 (41%) were married, 21 (22%) were separated and/or divorced and 18 (19%) were widowed. Out of those who were married, 5 (13%) of them, all females, have discordant sero-status families.

In terms of the reactions of PLWHA on learning about their HIV sero-status, the findings show that PLWHA reacted in various ways when they first learnt of their HIV positive sero-status. The commonest thing 29 (30%) males and 30 (31%) females did was to attempt suicide. Also 20 (21%) females and 5(5%) males withdrew from public functions; while a negligible proportion 3 (3%) females and 6 (6%) males joined the network of PLWHA. The rest of the PLWHA took actions like such as resigning fate to God, buying drugs from patent medicine stores to treat themselves, confiding in the Pastor, and going to herbalists for treatment. Out of the number studied, only 2 (2.1%) of them, all females, reported that they told their family members but they also complained of maltreatment after disclosure.

In order to note the extent to which PLWHA accept their sero-status, they were asked their perceptions about HIV positive test. Findings showed that PLWHA viewed HIV positive test as synonymous with death, hatred, abandonment, rejection, stigmatization, and violence. A good number of PLWHA had the notion that life is ‘not worth living’ with HIV positive status. Stigma and discrimination were identified as the main problems of HIV test. Some PLWHA 33 (34%) females and 17 (18%) males complained of being badly treated, blamed and disowned for testing positive.

One of the main factors that influenced childbirth choices of PLWHAis cultural stigma. This was also amongst the factors that encouraged childbirth choices of some PLWHA. A good number of the female PLWHA during the focus group discussions reported that they were accused of causing the death of their husbands and as such, were subjected to inhuman treatment. Quoting from four female PLWHA, “we were pregnant when our husbands died but our husbands’ relatives accused us of extra-marital sexual relationships. As such, we were confined to places where we were denied access to antenatal and obstetric care. We were strictly monitored for probable prolonged labour during childbirth so as to justify their accusations and apportion more punishments.”

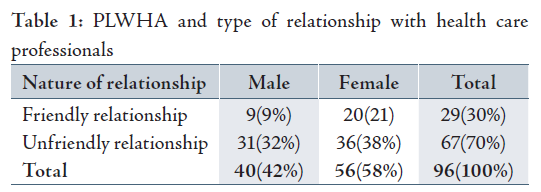

The findings revealed that the most worrisome factor that encouraged a good number of PLWHA to have babies outside the hospital was the unfriendly attitude of health workers. Quoting from six PLWHA “the nurses and laboratory attendants are very unfriendly, they shout, boo and curse us during health care services.” (Table 1)

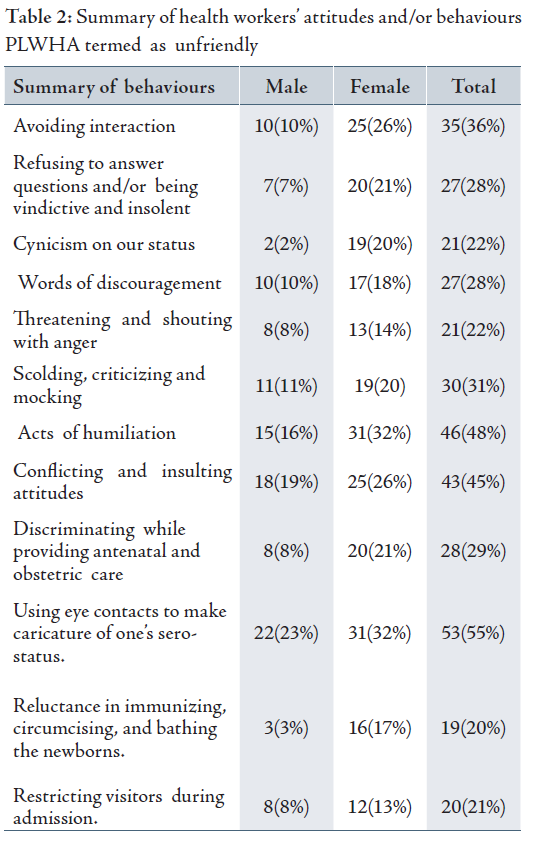

From these findings, both male and female PLWHA 67 (70%) reported unfriendly relationship with health care workers. Particularly mentioned were Nurses and Laboratory Scientists. The attitudes and/or behaviors of the health care workers that PLWHA termed as unfriendly were explored. (Table 2 contains summaries of some of the responses)

From the summary in Table 2, the commonest unfriendly attitude 53 (55%) PLWHA encountered with health workers was using eye contacts to make caricature of their sero-status.

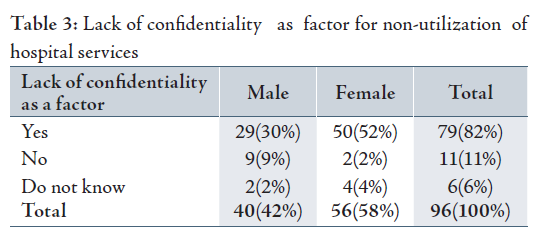

Lack of confidentiality was a factor in

non-utilization of hospital services. A good number of the PLWHA reported that

“they withdrew from hospital

services because the nurses told

others about their sero-status.” As high as 79 (82%) PLWHA did not use hospital

services because of non-confidentiality. (Table 3 for details)

Further probing during the focus group discussion, revealed that nurses and laboratory scientists carelessly disclosed PLWHA sero-status to others without their consent. Quoting from four PLWHA, “the nurses and laboratory scientists are wicked. They

told others about our HIV test results.” One of the PLWHA reported that “I am ashamed at the behavior of the Doctor who treated me. The Doctor went about telling people in the community including church members that I have AIDS and that I should be isolated. Since then, I have neither gone to his clinic nor to Church. As a result of the Doctor’s actions, people jeer at me anytime I pass. It was after I joined the network that I was encouraged and now, I no more bother about such actions.”

Discrimination was one of the factors the majority of PLWHA reported to have influenced their childbirth choices during focus group discussion. Quoting from six PLWHA, “the nurses and laboratory scientists discriminate against us. The nurses wear hand gloves when giving us drugs as opposed to what they do to other patients. If there were no gloves for nurses to wear, they would throw the drugs at us. For the laboratory scientists, they usually fling our HIV result on us thereby indirectly telling others about our sero-status.”

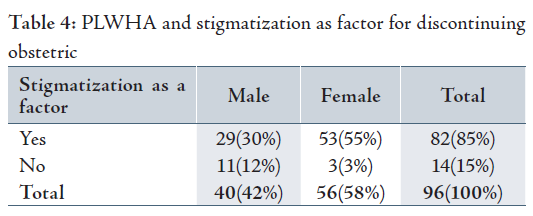

A good number of PLWHA during the interview and focus group discussion reported that stigmatization affected their childbirth choices. As high as 82 (85%) PLWHA reported that antenatal and obstetric services were discontinued as a result of stigmatization. (Table 4 for details)

PLWHA mentioned that some of the attitudes health workers meted to them indicated stigmatization. For instance, ten PLWHA reported that “health workers jeered at us, called us dishonorable names, and even denied us medical attention.” Using the report of one PLWHA, “because my wife is HIV positive, health workers in my community health center humiliated and denied her antenatal care (ANC) and obstetric care. Subsequently, I registered her with a traditional birth attendant (TBA) in the community. The TBA gave her antenatal services on the first visit. On the second visit, the TBA refused her medical attention stressing that health workers in the health care center warned her not to attend to my wife again because of her HIV status. I felt bad and abused the nurses for their dastardly act. After that encounter, my wife then registered with another TBA outside the community. There she eventually had her baby.”

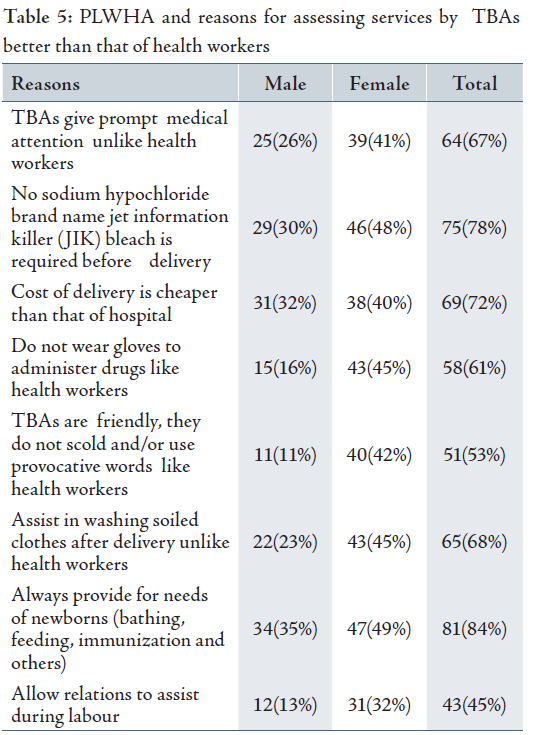

A good number of the PLWHA perceived services they received from health workers as very poor. They assessed services provided by TBAs at home as better than that of health workers in hospitals. Subsequently, the PLWHA were requested to give reasons for their assessment. (Table 5 contains some of the reasons)

The findings show that the most popular (81 (84%) PLWHA) reason for assessing services given by TBAs as better than that offered by health workers was that TBAs always provided the needs of newborns. They emphasized that while health workers grudgingly clean, dress, and/or immunize their newborns, that TBAs gladly provide these services. They reiterated that if not for the intervention of TBAs, their newborns especially males, would remain uncircumcised. From the females’ responses, there was no identifiable strategy mounted by the health workers in the hospitals to assist HIV positive women during pregnancy and childbirth.

During the focus group meeting, a good number of PLWHA complained of non-acceptance by health workers. Majority of the PLWHA mentioned a list of variables that connoted non-acceptance. Seven PLWHA quoted “we stopped attending ANC because the nurses at ANC examination rooms would scold, abandon and/or boo at us especially when we delay in undressing before they (nurses) enter the examination rooms.” One PLWHA specifically reported that “Nurses would deliberately fail to give appropriate instruction on what to do and/or where to go during ANC so as to scold and ridicule someone.”

PLWHA complained of long waiting hours during ANC. Although findings showed that PLWHA had designated hospitals for their regular antenatal care services, yet 52 (54%) reported waiting for more than 2 hours before receiving medical attention. A good number of them confirmed that on several occasions, they had to abandon ANC services for maternity homes where they received prompt attention.

PLWHA also complained that high treatment bills influenced their childbirth choices. The findings showed that PLWHA paid as high as US $115 for laboratory investigations, and delivery charges. Also, they spent between US $6 to US$ 54 on monthly transportation to the ANC venue, and US $46 for hospital bed charges. In addition to these bills, the hospital would expect a carton of JIK bleach, and three packets of disposable gloves from each PLWHA during childbirth. Four PLWHA reported “when we had our babies in the hospital, our discharge was delayed because we were unable to pay our bills. We had to borrow money to defray the hospital bills before we were finally discharged home.”

Consequently, PLWHA compared the cost for

having babies with health workers in hospitals and that with TBAs at home.

Findings showed that it costs as low as N500– N3,000 (US $3.8-US

$23) to have babies with TBAs and as high as N43,000 (US

$331) with health workers. One respondent reported, “PLWHA do not have such

money to waste when we can get better services elsewhere at a cheaper rate.

PLWHA complained of long distances to access ARV and ANC services. Approximately 32 (33%) females reported traveling between 32-65 kilometers to access ARV and ANC services. Also, 25 (26%) males reported of traveling up to 65 kilometers to access ARV at a cost of $100 while 11 (12%) said they travel as far as 770 Kilometers to access ARV at a cost of US $ 8. In total, 6 (6%) PLWHA did not respond because they reported that they were not on drugs.

This study aimed to explore the extent to which PLWHA disclosed their sero-status to contact persons including family members, health workers, and TBAs. The finding revealed that majority of PLWHA did not disclose their sero-status to others. Of the 41 (43%) PLWHA who reported that they had their babies with TBAs at home, none of them admitted that they disclosed their sero-status to the TBAs.

Realizing the danger inherent in non-disclosure, PLWHA were hypothetically asked whether “If you were diagnosed living positively with HIV before or during pregnancy, and your health care provider does not insist that he/she knows your sero-status before childbirth, would you like to disclose to him/her your sero-status yourself or tell someone else to do so?” The question enabled the researchers to note the extent to which TBAs and other health workers are exposed to HIV infection in the course of discharging their functions. This question brought a lot of confusion as a good number of PLWHA responded in the negative. About 52 (54%) females and 38 (39%) males responded that they would not disclose their sero-status for reasons of rejection, isolation and stigmatization.

PLWHA were also asked “who makes the decision on where childbirth takes place in the

family?” The responses to this question showed that males had greater influence

on childbirth choices than females. A total of 43 (45%) females and 27 (28%)

males admitted that generally, males decided childbirth choices while 7

(8%) females and 12 (13%) males said females decide childbirth

choices. Overall, 61 (64%) PLWHA,

comprised of 45 (47%) from the rural and 16 (17%) from semi-urban areas had babies with TBAs at home.

Realizing the number of PLWHA who had childbirth with TBAs at home, they were asked whether they perceived that there could be risks of obstetric complications during childbirth at home. The results showed that neither TBAs nor PLWHA viewed having obstetric complications during childbirth at home as a concern. Pregnancy was termed as a natural phenomenon for which no special attention should be required.

One important finding in this study was that majority of PLWHA had absolute confidence in the professional skills of TBAs. They (PLWHA) were of the opinion that whatever complications that arose during childbirth with TBAs, that the TBAs would competently handle such complications. This confidence on the effectiveness of TBAs in managing obstetric complications may have partly contributed to the decision of male PLWHA to prefer their wives to have childbirth with TBAs at home than with health workers in hospitals.

Perhaps, the most provocative finding was the fact that during the focus group discussion, a good number of PLWHA reported that they discontinued use of iron tablets and/or ante-retroviral (ARV) drugs for the unconvincing reasons of having big babies and threatened abortion respectively. This practice showed that PLWHA lacked knowledge of the advantages of iron tablets and ARV during pregnancy.

There was substantial need to determine the extent to which PLWHA and their newborns were protected from HIV infection and/or re-infection during childbirth. To ensure this, they were asked whether they had been taught the dangers of having frequent pregnancies, and/or discussions on reasons to limit pregnancies. Findings showed that 26 (27%) of the females and 9 (10%) males admitted having been taught the dangers of having frequent pregnancies, while 21 (22%) females and 12 (13%) males reported that they have had discussions on why people should not have many children. The rest responded in the negative.

During focus group discussion, the study noted five main concerns of PLWHA. Firstly, accessing free medical services. Majority of PLWHA reported that they paid for virtually all services they received. Secondly, having meaningful means of livelihood. A good number of PLWHA including those working in hospitals affirmed that they lost their jobs while those in school reported that they quietly withdrew from school as a result of their sero-status. Thirdly, they were concerned on increased acceptance. Majority of the PLWHA worried about being stigmatized and discriminated against in the society. Fourth, on having more babies for social acceptability. A good number of the female PLWHA complained of difficulty in getting pregnant as a result of irregular menstruation. Culturally, the more children one has, the richer and more socially acceptable the individual would be assessed. Fifth, on improved relationship with health workers. Majority of the PLWHA complained of constant interpersonal conflicts with health workers.

The health workers studied comprised of 20 (44%) males and 25 (56%) females between the ages of 21-59 years. They constituted of 12 (26%) nurses, 5 (11%) laboratory scientists, 4 (9%) Pharmacists, 19 (42%) medical doctors, and 5 (11%) TBAs. In terms marital status, except 8 (18%) that were single, the rest were married.

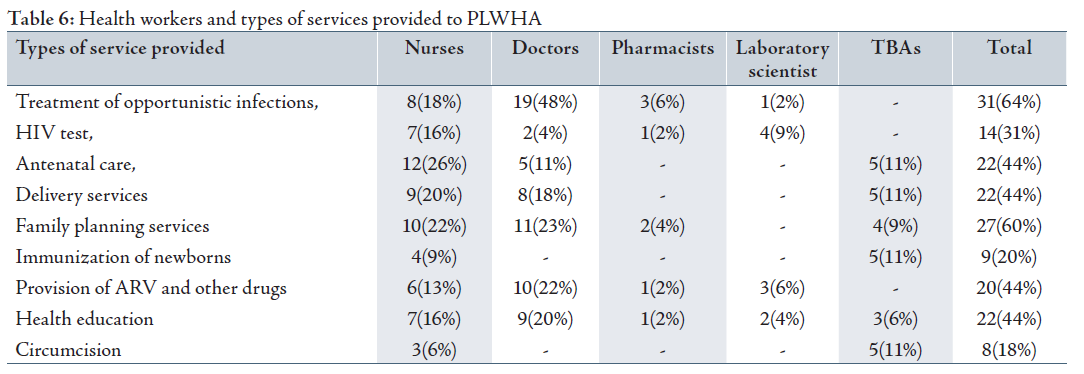

The health workers were asked to enumerate types of services each provide to PLWHA. (Table 6)

The findings showed that the commonest service health workers provided to PLWHA was treatment of opportunistic infections. Only few nurses provided circumcision and immunization to the children of PLWHA. Quoting from three nurses, “expecting us as nurses to immunize and circumcise children of PLWHA who may also be infected, would mean exposing us and others to risks of HIV infection.” Furthermore, analysis of the findings revealed that none of the health workers studied mentioned counseling whether for HIV or general counseling as one of the services they offered to PLWHA.

Health workers were asked the extent to which they insist on knowing the sero-status of those they served. From the responses, only 13 (29%) of the health workers mainly Doctors reported that they insist on knowing the HIV status of patients and even refer some to laboratory test. Others reported that they do not insist on knowing patients’ HIV status because of misunderstandings and personality clashes with patients.

Health workers were asked of their relationship with PLWHA. To determine this, some indices on good relationship were provided. The finding showed that 32 (71%) of health workers especially nurses and laboratory scientists had had some disagreements with PLWHA. Three nurses reported “we are careful in dealing with PLWHA because they are very violent, obstinate, abusive and are prepared to fight at the least provocation.” Specifically, two laboratory scientists narrated instances where PLWHA exhibited acts of aggression on receipt of their HIV test results.

The extent to which health workers including TBAs protect themselves and/or the newborn against HIV infection was explored. To ensure this, health workers were requested to mention HIV prevention strategies they used when providing services to PLWHA. The findings showed that health workers

adopted a limited number of prevention strategies including PMTCT measures during services. From the findings, 15 (33%) Doctors said they used Caesarean sections, administration of ARV to pregnant women from the third month of gestation, and also to the new born to prevent PMTCT. The rest of the health workers, 30 (57%) admitted they used only globes, sterilization of all instruments, JIK bleach, and apron to prevent HIV infection. From these findings, none of the health workers used other universal precautionary measures to protect themselves and others against HIV infection when providing services.

There was need to note the extent to which the health workers were exposed to trainings on HIV and AIDS. To record this, the health workers were requested to list as many training exposures they had received on HIV and AIDS. The findings showed that a total of 29 (64.4%) of the health workers said they had attended training seminars and workshops on advocacy, awareness creation, emergency obstetric care techniques, pathogenesis and treatment. The rest reported that they had not been trained.

The health workers had six striking concerns. Firstly, how to manage aggressive tendencies of PLWHA. Secondly, the negative policy on free treatment for PLWHA. The amount of money PLWHA pay for hospital services justifies this concern. Thirdly, the fear of being infected. The numbers of health workers in the study group especially nurses who are already infected could heighten this concern. Fourth, the incidence of obstetric problems due to constant pregnancies among PLWHA. Fifth, the inaccessibility of drugs especially ARV for PLWHA. Sixth, the need to attract sponsorships to conferences, seminars and workshops both nationally and internationally.

DISCUSSIONThis study provides confirmation to the multiple risks PLWHA take in their childbirth choices. Striking similarities on information given by both health workers and PLWHA confirm that factors such as unaffordable hospital fees, inaccessible hospital services, poor quality services, lack of confidentiality, stigmatization, poor interpersonal relationship, and others encouraged childbirth choices at home.

Among the factors that influenced childbirth choices at home, poor interpersonal relationships with health workers remained the most important factor that influenced PLWHA childbirth choices with TBAs at home. Nearly two thirds of the PLWHA who had childbirth at home with TBAs did so as a result of poor interpersonal relationships with health care professionals. PLWHA assessment of poor interpersonal relationship was largely based on the experiences they had with health workers during ANC and obstetric services. For instance, PLWHA enumerated actions such as beating, scolding, shouting, name calling, discriminatory provision of health care services and other health workers meted to them that amounted to poor interpersonal relationships. This finding on poor interpersonal relationship is relevant because measures to improve interpersonal relationships constituted the major concerns of both the PLWHA and the health workers. The finding that PLWHA had poor interpersonal relationship with health workers was also confirmed in other studies.1,3 This poor interpersonal relationship could be part of the reasons why PLWHA perceived the services of TBAs better than that of health workers. The fact that TBAs undertook to immunize and circumcise PLWHA newborns and also assisted in cleaning blood and mess after childbirth shows that health workers in hospitals had little or no plans to assist HIV positive women during pregnancy and child birth.

Therefore, it is felt that if health workers in hospitals promote positive values and avoid interpersonal conflicts with PLWHA, such could constitute motivating factors to increase PLWHA childbirth choices in hospitals. This is necessary because full ANC and obstetric care services provided by health workers in hospitals rather than that by TBAs at home will likely reduce the risk of mother to child transmission (MTCT). PLWHA preferring childbirth at home with TBAs than with health workers in hospitals could result in apparent increased risk of mother-to- child transmission (MTCT).

The fact that males had the prerogative to decide childbirth choices for PLWHA suggests that male dominance and power imbalances in the family set up also apply to PLWHA. The finding that males influenced decisions on childbirth choices of PLWHA agrees with that reported that males take most decisions in the family.5,7,8 Unfortunately, the subordinate positions of women including PLWHA limit their participation when family issues including childbirth choices are discussed.

Reviewing the social environment to a large extent, there was poor knowledge of HIV prevention methods among the participants. This poor knowledge could be a reflection of inadequate exposure to seminars, conferences, workshops and trainings. This was noted by the limited use of universal prevention measures health workers adopted during health services. There was also limited knowledge on benefits of PLWHA disclosing their sero-status to contact persons including health workers. This limited knowledge which is detrimental to HIV prevention and the finding calls for adequate intervention strategies to enlighten participants on benefits of disclosing HIV sero-status.10,13,14

Another inertia to poor knowledge of HIV prevention is the unwillingness of PLWHA to take either ARV or iron tablets due to fear of abortion and/or having large babies. There was fear that taking iron tablets during pregnancy could result to having large babies. Having large babies connoted attracting extra expenditure for their husbands because of the likelihood of undergoing Caesarean operation which could occasion loss of life. Also, taking ART during pregnancy was implicated as the cause of incessant abortion among PLWHA.

CONCLUSIONThe findings from this study provide valuable information on factors determining childbirth choices of PLWHA. These factors need to be taken into account when policy makers are planning and/or providing services to PLWHA. For example, Government should be made aware that PLWHA need to be supported and encouraged through training to enable them to learn more about their reproductive health rights as well as the benefits of childbirth in hospitals.

Regular training and retraining is crucial for health workers. Emphasis should be laid on regular training of health workers on benefits of good interpersonal relationships, as well as in all aspects of HIV preventions. There should not be an assumption that health workers are knowledgeable and competent. However, PLWHA and health workers, regardless of their personal HIV prevention experience, need sufficient HIV prevention knowledge and good interpersonal skills so that they can confidently minimize HIV infection and MTCT.

The health workers should assist PLWHA with obstetric and other problems needing prompt medical attention. This recommendation necessitates the importance of health workers to mainstream services to PLWHA to enable them to make adequate use of hospital services during pregnancy and childbirth. This recommendation is premised on the fact that PLWHA, because of poor interpersonal relationships they experienced with health workers especially nurses, tended to patronize childbirth at home with TBAs rather than in hospital with health workers. There is great need for policy makers to address the plight of PLWHA by funding periodic seminars for PLWHA and health workers.

Bills for services rendered to PLWHA should be free or at least a token. Free services will motivate PLWHA to patronize health workers in the hospitals.

There is need for more detailed research to be conducted on the plight of PLWHA during health services. Elaborate research will highlight the areas policy makers, stakeholders and gatekeepers need to pay more attention in the implementation of HIV and AIDS prevention. The findings of such study will also alert them on the actual problems PLWHA face.

Authors acknowledge organizers of the international conference for Third World Organization of Women in Sciences (TWOWS) in Bangalore, for the opportunity to undertake this work and for sponsorship. We thank the Ministry of Health for approving the study the PLWHA for volunteering. There is no conflict of interest. The researchers bore all the financial implications of this work. The study was conducted n order to contribute towards the well being of people living positively with HIV and AIDS.

-

Akinrinola B, Susheed Singh. Vanessa, Woog and Deirdre Wulf. Risk and protection, Youth and HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Alan Guttmacher Institute New York 2004.

-

The National AIDS/STD Control Programme. Federal Ministry of Health. Prevalence survey in Nigeria, Nigeria Journal of General Practice, 1:7-8.

-

OmikanFD. Nurses knowledge and skills about caring for patients with HIV/AAIDS in Osun State Niger Journal of Medicine 2001; 10:30-33.

-

Adebanjo SB, Bamgbala AO, Oyediran MA. Attitudes of Health Care Providers to Persons Living with HIV/AIDS in Lagos State, Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health 2003; 103-112.

-

Ransom E, Yinger N. Making motherhood safer: overcoming obstacles on the pathways to care. Washington DC. Population Reference Bureau 2002.

-

Ainma JIB, Okeke AO. Contraception: Awareness and Practice Among Tertiary School Girls . West African Journal of Medicine 1995; 14:34-38.

-

Aboyeji AP, Fawole AA, Ijaiya MA. Knowledge of an Attitude to Antenatal Screening for HIV/AIDS by Pregnant Mothers in Ilorin Nigeria . Nigeria Quarterly Journal Hospital Medicine 2002; 10:181-184.

-

Adeokun L. Promoting dual protection in family planning clinics in Ibadan, Nigeria. International Family Planning Perspectives 2002; 2:87-95.

-

Dare OO, Oladepo O, Cleland JG, Badru OB. Reproductive Health Needs of Young Persons in Markets and Motor Parks in South West Nigeria. African Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences 2001; 30:199-205.

-

NYSC Reproductive Health and HIV/AIDS Prevention Project. Manual for Training trainers of Peer Health Education. 2003; 1-15 .

-

National HIV/AIDS Behaviour Change Communication 5-year Strategy (2004-2008). 2004; 1-10.

-

Adebayo SB, Bamgbala AO, Oyediran MA. Attitudes of Health Care Providers to Persons Living Positively with HIV/AIDS in Lagos State, Nigeria. African journal of Reproductive Health 2003; 7:103-112.

-

Nyblade L. Choosing between two stigmas: the complexities of childbearing in the face of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa . Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America 2002, May 9-11., 1-9.

-

Suzanne F, Heidi R, Irina Y, Babara B, Jane S. HIV Counseling and Testing for Youth. Edited by Finger W. 2005.

-

Heidi WR. Use of maternal and Child Health Services by Adolescents in Developing Countries. YouthNet Briefs on Reproductive Health and HIV/AIDS June 2005, No. 1

-

Odusanya OO, Alakija W. HIV, Knowledge and Sexual Practices Amongst Students of School of Community Health in Lagos, Nigeria. African Journal of Medicine and medical sciences 2004; 33:45-49.

-

Loewenson R. HIV/AIDS implication for poverty reduction, New York, United Nations Development Programme 2001.