Post Traumatic Buccal Fat Pad Injury in a Child: A missed entity in ER

Maneesh Singhal and Sushma Sagar

doi:10.5001/omj.2010.70

ABSTRACT

Maxillofacial injuries in the paediatric age group is common and traumatic herniation of buccal fat pad represents one of the few sequel to facial injuries which can easily be missed during primary or secondary survey in the emergency department, especially in young patients. The uncommon occurrence and thus lack of knowledge, often alarms the parents and/or attending physian alike with the presence of a tumor like lesion within the oral cavity in the post-traumatic period. The following case report describes one such incidence of traumatic extrusion of the buccal fat pad into the oral cavity while addressing the need to reinforce the practice of thorough clinical examination before managing any patient.

From the 1Department of Surgery, JPN Apex Trauna Center, AIIMS,

New Delhi.

Received: 19 Mar 2010

Accepted: 22 Apr 2010

Address correspondence and reprint request to: Dr. Sushma Sagar, Department of Surgery, JPN Apex Trauna Center, AIIMS, New Delhi, 110029 India.

E-mail: sagar.sushma@gmail.com

INTRODUCTION

The buccal fat pad is responsible for the fullness of the cheeks in young children. At the same time, it aids cushioning and sucking functions. It is prominent in neonates and infants and is often referred to as the “Sucking/Suctorial” pad.1,2 The buccal fat represents a specialized type of tissue that is distinct from subcutaneous fat. It serves to line the masticatory space, separating the muscles of mastication from each other, from the zygomatic arch, and from the ramus of the mandible.

The buccal fat pad had limited clinical importance for many years and was usually considered a surgical nuisance because of its accidental encounter either during various operations in the pterygomaxillary space or after injuries of the maxillofacial region. It is currently of interest in aesthetic surgery, as in buccal lipectomy in adults to modify the contour of the face.3 During the past few years reports have encouraged the use of buccal fat pad for reconstruction of oral defects. The easy mobilization of the buccal fat pad, excellent blood supply and minimal donor site morbidity make it an ideal flap.4 Herniation of this tissue into the oral cavity by blunt trauma to the face is rare and often skips initial examination. Such an instance is presented in the following case report.

CASE REPORT

A five year old male was brought to the trauma unit with extensive laceration of the scalp suffered as a result of a fall from height while playing. On Initial assessment (Primary survey) in the Emergency Room, the airways, breathing and circulation were all fine. Detailed examination (secondary survey) later revealed a 10 cm lacerated wound over the scalp region. Extra oral examination of this otherwise healthy and active child revealed a slightly diffused facial swelling on the right side of the cheek. CT scan ruled out the presence of any facial fracture. Intraoral examination could not be performed due to limited compliance from the child. Since vital parameters were normal, no immediate resuscitation was required. The patient was sent to the Operating room for closure of the scalp wound and thus further examination was planned under anaesthesia. (Figs. 1 & 2)

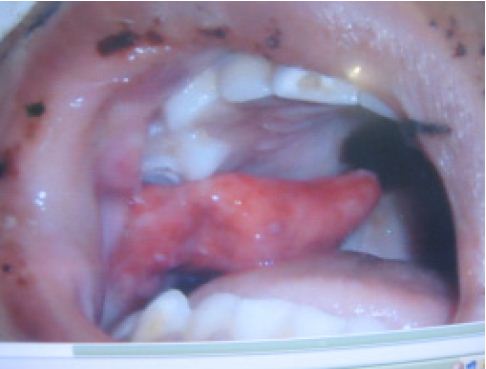

Figure 1: Pre-operative intraoral image showing buccal fat pad herniation on right side Post-operative intraoral image after closure.

However, during intubation a yellowish brown, freely mobile, soft pedunculated projection from the right buccal mucosa at the level of the occlusion of primary molars was seen. When retracted, a 1.5 cm laceration of the buccal mucosa was noticeable. The mass was homogenous and a provisional diagnosis of traumatic herniation of buccal fat of pad was made. The parents were questioned and any evidence of earlier such presence of buccal swelling was ruled out. The mass was partially excised and the rest was pushed in the pocket. Primary closure was achieved. Post-operatively, antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs and an antiseptic mouth rinse were prescribed. The swelling subsided and healing was uneventful.

Figure 2: Post-operative intraoral image after closure

The histopathological examination of the tissue confirmed the earlier made provisional diagnosis of buccal pad fat herniation. The haemotoxylin and eosin stained sections revealed connective tissue stroma with groups and sheets of lipocytes, interstitial spaces occupied by abundant polymorphonuclear leucocytes and a few foamy macrophages. The child was discharged after a week.

DISCUSSION

Complications arising from maxillofacial trauma may occur immediately following the injury during transit to the hospital in the pre-operative, intra and postoperative phases. Some complications may not arise until months or even years after the injury.5 It is difficult to perform complete examination in young traumatized children and history given by parents may not always be adequate. The children are extremely difficult to evaluate.

In this patient, the scalp was profusely bleeding, which could have endangered the circulation profile of the patient, and moreover the airway was not threatened, so no further consideration was given to the intraoral status initially, and patient was rushed to the operating room. This represents the common trend amongst Emergency physicians to overlook such intraoral injuries even in adults. This report aims to highlight this fact so that such missed diagnosis can be prevented with high index of suspicion for such injuries.

Review of literature revealed that traumatic herniation of buccal fat pad is a rare phenomenon. Most reported cases were of infants or young children with an age ranging from 5 months to 5 years. Injuries are usually by a foreign object such as a pencil, when held in the mouth resulting in puncture wounds of the buccal mucosa. Further sucking action may result in the fat pad being pulled out. The most characteristic aspect of this lesion is that the mucosal injury or perforation may be very small compared to the size of the extruded mass.

The principle muscle of the cheek is the buccinator which invests the buccal fat pad or Bichat’s pad on its outer aspect.6 The buccal mucosa can be traumatized by the teeth in an accident such as falling off a bicycle. An external force may also cause rupture of the buccal mucosa, as in the case reported here. There has also been

a case reported in which herniation of the buccal fat pad into the maxillary sinus occurred associated with the fracture of the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus, following a blow to the face.7

As reported in literature, extra oral herniation is mentioned as pseudoherniation of the buccal fat pad or ‘Chipmunk cheek’ caused mainly by surgical trauma.8

Tumors such as lipoma, traumatic fibroma (inflammatory hyperplasia) salivary neoplasm hemangioma forms the differential diagnosis.2 However, the history of trauma, absence of prolapse before the injury, its occurrence in infants and young children, specific anatomic sites, adipose appearance, locating the perforation from where the mass is arising and the histopathology, are the characteristic features important for diagnosing the condition. As for the treatment, an alternative to excision is to reposition the herniated buccal fat pad to its anatomic position at the earliest, before a large portion is allowed to extrude, followed by primary closure.5 Being relatively avascular, fatty tissue when damaged has a tendency to necrose or undergo atrophy.9 Infection and inflammatory reaction due to salivary contamination, bacterial aggregation and necrosis of the tissue due to occlusal trauma and delay in treatment can often complicate the situation, although partial conservative excision may seem to be a better option. Removal of the fat pad may produce a change in the facial contour, reducing cheek fullness, highlighting the malar eminences and giving a more sculptured look to the face. Since buccal fat pad is intimately related to the masticatory muscles, facial nerve and parotid wound, great care must be taken to avoid injury to the parotid duct, by locating the parotid papilla. Exploration for foreign bodies and irrigation are important before closing the wound. There have been no reports of recurrence of herniation or any other complications.

CONCLUSION

Traumatic herniation of the buccal fat can be seen in young patients with blunt facial injuries. The diagnosis becomes difficult in view of lack of patient cooperation and/or adequate examination of the oral cavity in the emergency department. The diagnosis may further be overshadowed in cases where life threatening conditions require major attention. The possibility of occurrence of such a condition, however, should be included while screening the oral cavity in the ED, especially in young patients with maxillofacial injuries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors reported no conflict of interest and no funding was received on this work.

-

Messenger KL, Cloyd W. Traumatic herniation of the buccal fat pad, Report of a case. Oral Surg 1977; 43(1):41-43.

-

Wolford DG, Stapleford RG, Forte RA, and Heath M. Traumatic herniation of the buccal fat pad. J Am Dent Assoc 1981; 103(4):593-594.

-

Stuzin JM, Wagstrom L, Kawamoto HK, Baker TJ, Wolfe A. The antomy and clinical applications of the buccal fat pad. Plast reconstr Surg 1990; 85(1):29-37.

-

Baumann A, Ewers R. Application of the buccal fat pad in oral reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofacial Surg 2000; 58(4):389-392.

-

Takenoshita Y, Shimada M, Kubo S. Traumatic herniation of the buccal fat pad: Report of case. ASDC J Dent for Child 1995; 62(3):201 -204.

-

Fritsch H, Kühnel W. Color Atlas of Human Anatomy: 5th ed. Thieme, 2007: 144-146.

-

Marano PD, Smart EA, Kolodny SC. Traumatic herniation of the buccal fat pad into maxillary sinus. Report of case. J Oral Surg 1970; 28(7):531-532.

-

Matarasso A. Pseudoherniation of the buccal fat pad: a new clinical syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997; (100):723-730.

-

Leopard J. Complications in maxillofacial injuries. Row N.L and Williams J.L. 2nd Edition, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1994: 845-853.